In 1825 Alabama welcomed the Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette as part of his grand tour of the United States. (Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress)

In 1825 Alabama welcomed the Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette as part of his grand tour of the United States. (Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress)

In 1825 Alabama welcomed the Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette as part of his grand tour of the United States. (Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress) In 1825 Alabama welcomed the Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette as part of his grand tour of the United States. (Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress) On December 14, 1819, mere days before the first state legislative session in Huntsville formally closed, Pres. James Monroe signed the long-awaited congressional resolution proposing Alabama’s formal admission into the union. With that signature, a moment over two decades in the making finally arrived, and Alabama officially became the United States of America’s twenty-second state. A pivotal era of transition, bridging the lengthy metamorphosis from backwoods frontier to dynamic heart of the antebellum Deep South, immediately began.

0 Comments

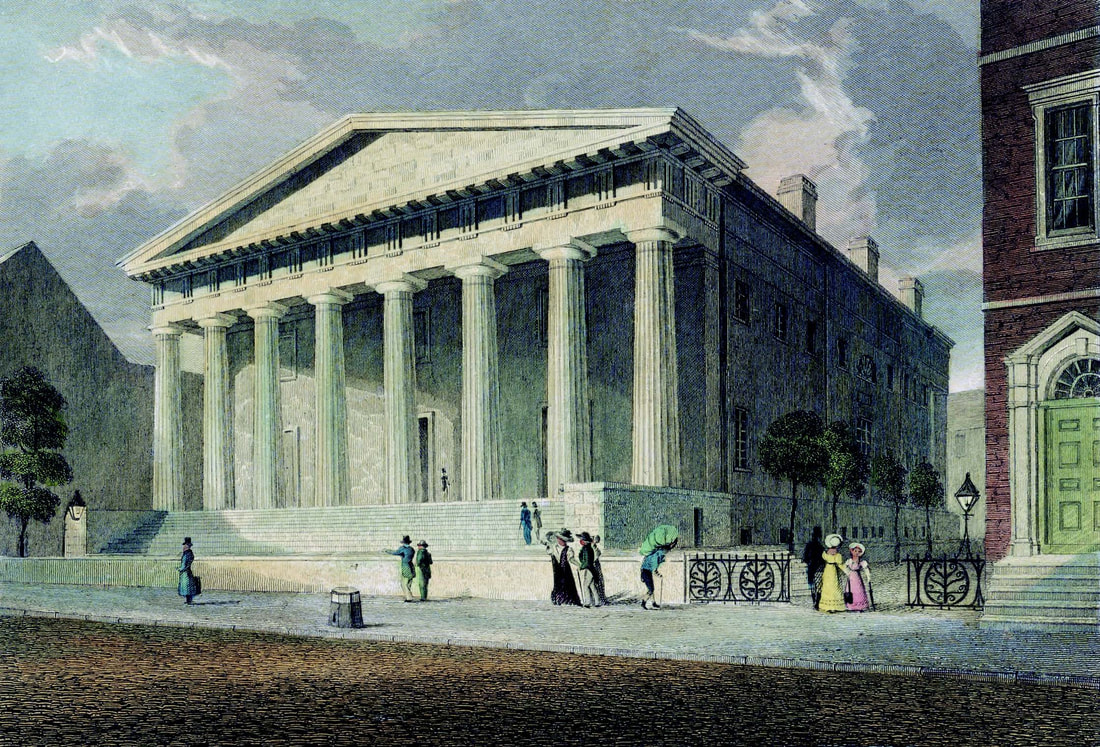

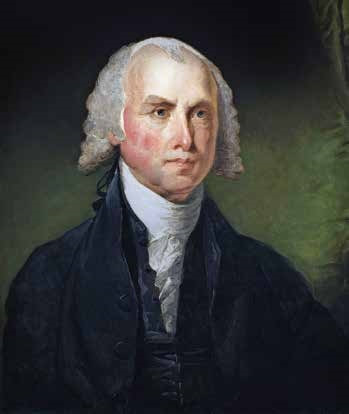

Vine Street was the main thoroughfare through Cahawba. During the town’s later incarnation as a cotton port, shops and businesses lined the street, alongside the Dallas County Courthouse. The buildings are gone, but the street is still lined with Chinaberry trees. A town statute required all residents to plant the trees for shade. (Robin McDonald) Vine Street was the main thoroughfare through Cahawba. During the town’s later incarnation as a cotton port, shops and businesses lined the street, alongside the Dallas County Courthouse. The buildings are gone, but the street is still lined with Chinaberry trees. A town statute required all residents to plant the trees for shade. (Robin McDonald) The eventful summer of constitution making behind it, Alabama’s state legislature opened its first session on October 25, 1819, in Huntsville. Gov. William Wyatt Bibb attempted to impress upon the legislators the solemnity of the occasion in a written address read to the body at its commencement by observing the gathering would “form a memorable epoch in our history…you cannot estimate too highly the great interests committed to your charge, or the important consequences which may flow from your deliberations.”  On June 1, 1819, the city of Huntsville was surprised by an unannounced visit by Pres. James Monroe, whose signature would admit the state of Alabama to the Union later in the year. (Library of Congress) On June 1, 1819, the city of Huntsville was surprised by an unannounced visit by Pres. James Monroe, whose signature would admit the state of Alabama to the Union later in the year. (Library of Congress) As if to underscore Alabama’s impending arrival on the national scene in the late spring of 1819, on June 1 Pres. James Monroe paid a surprise visit to the territory’s largest city, Huntsville. While Monroe’s arrival during a whirlwind tour of the southern states may have been unannounced, dumbstruck local officials managed to cobble together a proper banquet in his honor in short order. After leading lights paid their respects to the nation’s leader in a series of toasts given over a sumptuous meal, Monroe offered one of his own for the Alabama Territory that struck at the heart of what lay on everyone’s minds: “May her speedy admission into the Union advance her happiness, and augment the national strength and prosperity.” As the president spoke those words, the constitutional convention, which would frame the document to form the new state’s government and remove the final barrier between territory and statehood, lay only a month away.  The tight money policies of the Second Bank of the United States, headquartered in Philadelphia (above), were blamed for the length and depth of the recession following the Panic of 1819, particularly in the South and West, where borrowed money was needed to buy land on the frontier. The loss of credit caused many Alabama landowners to default on their loans. (Library of Congress) In many ways the year Alabama became a state stands as among the least auspicious of its tumultuous territorial experience. Shortly after the turn of the New Year in 1819, a land heretofore showcasing steady economic growth, generous and easy credit, wide-ranging speculation, and general optimism among a swelling population suddenly entered a severe economic downturn that threatened to reverse its previous progress. Known to historians as the Panic of 1819, this first major depression in US history struck Alabama particularly hard and carried far-ranging repercussions that resonated well into its first decade of statehood.

Governor Bibb surprised the territorial legislature by proposing the confluence of the Alabama and Cahaba Rivers (above), at the time an undeveloped wilderness, as the site of Alabama’s state capital. The site proved to be problematic as it was prone to flooding and occasional outbreaks of yellow fever. In 1825 Tuscaloosa was named as the new state capital. (Robin McDonald) In the late summer of 1818, a special-ordered seal and press designed for use by the Alabama Territory’s executive office finally arrived in St. Stephens from Philadelphia. The emblem featured a map of the territory showcasing its famed river system, the future state’s literal arteries of commerce. On the surface it seemed a common symbol of unity, highlighting the natural abundance that drew Alabama’s people together and augured a bright future. Viewed another way, however, the seal could be understood to reveal the underlying reasons for the territory’s pervasive sectional and political rivalries that seemed to only grow more pronounced as economic activity increased.

While most settlers who descended on the Alabama Territory hoped to carve farms and plantations from their little corners of the future state, others pursued a more urban vision of the path to prosperity. The year 1818 featured some of the Alabama Territory’s most frenzied and optimistic speculation, investment, and general dreaming and scheming in this regard. In one of the most elaborate examples of a common territorial phenomenon, for example the Cypress Land Company offered the first lots for sale in the planned city of Florence on July 22.

An engraving based on "Gang of Negro Slaves shipping Cotton from a Plantation on the Alabama River, by torchlight--on a Steam Boat for Mobile," painted by William Henry Brooke in 1839. (Alabama Archives) An engraving based on "Gang of Negro Slaves shipping Cotton from a Plantation on the Alabama River, by torchlight--on a Steam Boat for Mobile," painted by William Henry Brooke in 1839. (Alabama Archives) The Alabama Territory’s cultural and economic landscape was well defined by spring 1818. As the territory entered its second year of existence, cotton, transportation networks to facilitate its trade, and a fundamental reliance on slave labor had meshed to form the key parts of the structural bedrock on which the new state would rise. During the year ahead, these aspects of the territorial experience would both cement and extend their influence into virtually every aspect of Alabama life. One particularly significant area was transportation. Alabama’s first steamboats were a far cry from the floating palaces of river travel’s heyday—slower, smaller, and far less powerful or reliable than those of the coming generation—but they marked the beginning of the era of revolution in riverine transportation. On January 19, 1818, the members of the Alabama Territory’s legislature gathered in St. Stephens for the first of two lawmaking sessions conducted prior to statehood. All thirteen members present—twelve lower house members and one upper—originally had been elected to the Mississippi Territory’s General Assembly. To facilitate organizing the government of Alabama, the act enabling division of the territory had specified these representatives would serve the remainder of their terms as Alabama’s legislators. Befitting Alabama’s humble and hurried origins, they met in rented rooms at the Douglas Hotel. Appointed Gov. William Wyatt Bibb set the tone for administering business at hand in his written address to the assembly, which recommended careful attention to internal improvements and the promulgation of the means of education. Thus keeping one eye firmly on the future state they planned to erect, over the course of the next four weeks the legislators laid the groundwork for their own government.

“The Alabama Feaver [sic] rages here with great violence and has carried off vast numbers of our citizens,” wrote a startled North Carolinian to a friend in November of 1817. “There is no question that this feaver is contagious…, for as soon as one neighbor visits another who has just returned from the Alabama he immediately discovers the same symptoms which are exhibited by the person who has seen the allureing [sic] Alabama.” While these words may contain as much sarcasm as genuine alarm, the Alabama Territory did seem to possess a magnetic attraction to aspiring emigrants. The movement of people it inspired would become the enduring hallmark of Alabama’s formative years.

With the proverbial stroke of a pen in the nation’s capital, Alabama’s long road to independent territorial status entered its final act on March 3, 1817. The newly designated Alabama Territory, the eastern half of the enormous tract of the American southwestern frontier known as the Mississippi Territory, on that date began its transition to a separate political entity by the terms of an enabling act passed by Congress and signed into law by Pres. James Madison. The act set out the process by which the western portion of the territory, the future state of Mississippi, would enter the Union and organized the eastern section into the Alabama Territory. For the first time since the formation of the Mississippi Territory a generation prior in 1798, the circuitous path towards statehood for the region at last lay clear.

|

AuthorMike Bunn currently serves as director of operations at Historic Blakeley State Park in Spanish Fort, Alabama. This department of Alabama Heritage magazine is sponsored by the Alabama Bicentennial Commission and the Alabama Tourism Department. Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed