|

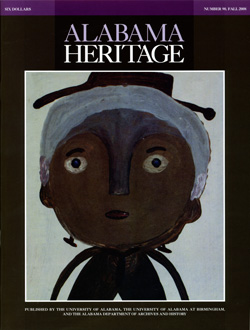

On the cover: Picture of Me (detail) by Mose T, circa 1975, 13 x 25 inches, house paint on wood paneling. (Collection of Anton Haardt.)

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

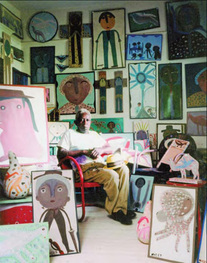

Mose T, surrounded by his creations

Mose T, surrounded by his creations(Henry Cadenhead)

Lilies, Jaybirds, and George: The Art in Mose T’s Trees

By Anton Haardt

A man of humble beginnings, Mose Tolliver—better known as Mose T—rose from obscurity to become one of America’s most celebrated folk artists. Tolliver’s paintings were fresh and unconventional. Before his fame reached its peak in 1982, they hung from trees outside his home in Montgomery and often sold (if they sold at all) for no more than three to four dollars a piece. Inspired by nature, this self-taught artist painted works that remain sought-after collectors’ items to this day. From the humble beginnings of painting on salvaged surfaces like birdhouses and scrap metal to a train ride to the nation’s capital where his work was displayed for First Lady Nancy Reagan in an illustrious gallery, Mose T became an iconic figure in the world of folk art. Collector Anton Haardt describes the life of the extraordinary man and the seminal exhibit that propelled Mose T to fame and helped solidify the importance of folk art to American culture.

By Anton Haardt

A man of humble beginnings, Mose Tolliver—better known as Mose T—rose from obscurity to become one of America’s most celebrated folk artists. Tolliver’s paintings were fresh and unconventional. Before his fame reached its peak in 1982, they hung from trees outside his home in Montgomery and often sold (if they sold at all) for no more than three to four dollars a piece. Inspired by nature, this self-taught artist painted works that remain sought-after collectors’ items to this day. From the humble beginnings of painting on salvaged surfaces like birdhouses and scrap metal to a train ride to the nation’s capital where his work was displayed for First Lady Nancy Reagan in an illustrious gallery, Mose T became an iconic figure in the world of folk art. Collector Anton Haardt describes the life of the extraordinary man and the seminal exhibit that propelled Mose T to fame and helped solidify the importance of folk art to American culture.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

About the Author

Adapted from Mose T A to Z: The Folk Art of Mose Tolliver

Anton Haardt has nearly twenty-five years of experience as an artist, folk collector, and mentor to folk artists. She earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the San Francisco Art Institute and now owns several galleries in the Southeast. Her own paintings and photography have been exhibited throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America. Haardt first met Mose T in 1970, and they remained friends until his death. Her current projects include a book about folk artist Juanita Rodgers. She presently lives in Montgomery with her son Haardt and their bull mastiff, Shakespeare.

Mose T A to Z: The Folk Art of Mose Tolliver is available in New Orleans at the Garden District Book Store on Prytania Street and the Anton Haardt Gallery at 2858 Magazine Street. You can find it in Montgomery, Alabama, at Mandy Bagwell Art, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Art, Capitol Book & News Company at 1140 E. Fairview Avenue and at the Anton Haardt Gallery at 1226 South Hull Street.

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

About the Author

Adapted from Mose T A to Z: The Folk Art of Mose Tolliver

Anton Haardt has nearly twenty-five years of experience as an artist, folk collector, and mentor to folk artists. She earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the San Francisco Art Institute and now owns several galleries in the Southeast. Her own paintings and photography have been exhibited throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America. Haardt first met Mose T in 1970, and they remained friends until his death. Her current projects include a book about folk artist Juanita Rodgers. She presently lives in Montgomery with her son Haardt and their bull mastiff, Shakespeare.

Mose T A to Z: The Folk Art of Mose Tolliver is available in New Orleans at the Garden District Book Store on Prytania Street and the Anton Haardt Gallery at 2858 Magazine Street. You can find it in Montgomery, Alabama, at Mandy Bagwell Art, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Art, Capitol Book & News Company at 1140 E. Fairview Avenue and at the Anton Haardt Gallery at 1226 South Hull Street.

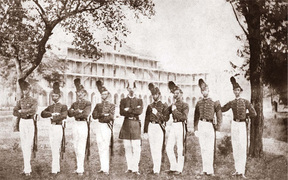

Ten years after the Civil War,

Ten years after the Civil War,a group of cadets pose on the campus quad

(W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library,

The University of Alabama)

Honorary Degrees for the Alabama Corps of Cadets

By Matthew C. Edmonds

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the duty-bound and rather “gung ho” Alabama Corps of Cadets of the University of Alabama itched to join the fight. Although denied formal permission by the University to suspend all their educational responsibilities, these cadets left en masse, eager to “see the elephant.” Many would never return, and those who did found only ash and rubble where their university had once stood. Some fifty years after the Civil War’s end, with the efforts of local members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, these soldiers were not only memorialized by a bronze plaque on a “handsome monolith of Georgia granite” on the UA campus, but with the help of UA President George H. Denny, they were also awarded honorary degrees for their sacrifice. The Alabama Corps of Cadets—some in person and some posthumously—received academic closure at last.

Additional Information

Alabama Civil War Service Database

About the Author

Matthew C. Edmonds is a Birmingham native who recently received his master’s degree from the University of Alabama, where he specialized in southern history. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia and currently teaches history and government at Saint Mary’s School in Raleigh, North Carolina. He would like to thank Lewis Dean of the Geological Survey of Alabama for his generous assistance in researching this article.

By Matthew C. Edmonds

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the duty-bound and rather “gung ho” Alabama Corps of Cadets of the University of Alabama itched to join the fight. Although denied formal permission by the University to suspend all their educational responsibilities, these cadets left en masse, eager to “see the elephant.” Many would never return, and those who did found only ash and rubble where their university had once stood. Some fifty years after the Civil War’s end, with the efforts of local members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, these soldiers were not only memorialized by a bronze plaque on a “handsome monolith of Georgia granite” on the UA campus, but with the help of UA President George H. Denny, they were also awarded honorary degrees for their sacrifice. The Alabama Corps of Cadets—some in person and some posthumously—received academic closure at last.

Additional Information

Alabama Civil War Service Database

- Blight, David. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001).

- Foster, Gaines M. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913 (Oxford University Press, 1988).

- Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (University of Georgia Press, 1983).

- Wolfe, Suzanne Rau. The University of Alabama: A Pictorial History, (University of Alabama Press, 1983).

- University of Alabama (UA)

- Wilson’s Raid

- Tuscaloosa

- Braxton Bragg Comer (1907-11)

- Alabama and the Civil War (feature)

About the Author

Matthew C. Edmonds is a Birmingham native who recently received his master’s degree from the University of Alabama, where he specialized in southern history. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia and currently teaches history and government at Saint Mary’s School in Raleigh, North Carolina. He would like to thank Lewis Dean of the Geological Survey of Alabama for his generous assistance in researching this article.

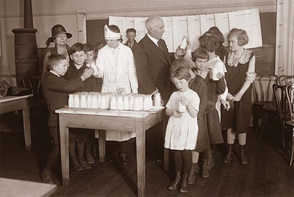

Children attend a nutrition class

Children attend a nutrition classgiven by the National Tuberculosis Association

(Library of Congress)

Captives of Consumption: Alabama’s Battle with Tuberculosis

By Alissa Nutting

Long known for its stubborn persistence and a staggering ninety-percent fatality rate, tuberculosis had claimed countless lives by the start of the twentieth century, indiscriminately affecting rich and poor, young and old, celebrities and common men. In the late 1800s, the sickness had claimed so many lives in Alabama that it was recorded as the leading cause of death in the state. Despite its seeming invincibility, Alabama health officials, medical practitioners, and civic organizations became committed to eradicating it somehow—or at least minimizing its impact. Over the decades, hopes were elevated by the construction of TB clinics and sanatoriums, aggressive public education programs, and the eventual identification of the disease’s source. By the mid-twentieth century, a vaccine for children at last set the coming generations free and rendered the horrors of “consumption” a relic of darker times. Former Alabama Heritage staff member Alissa Nutting looks at Alabama’s long journey from helplessness to empowerment over the indiscriminate air-borne killer.

Additional Information

The author wishes to thank the Alabama Department of Archives and History for providing invaluable information, in addition to acknowledging the following sources:

About the Author

Alissa Nutting is a PhD candidate in creative writing and a Schaeffer Fellow in fiction at the University of Nevada—Las Vegas. She received her MFA from the University of Alabama, where she edited the Black Warrior Review literary magazine and served as an assistant editor at Alabama Heritage. Her writing is forthcoming or recently published in magazines such as Denver Quarterly, Fence, and Tin House.

By Alissa Nutting

Long known for its stubborn persistence and a staggering ninety-percent fatality rate, tuberculosis had claimed countless lives by the start of the twentieth century, indiscriminately affecting rich and poor, young and old, celebrities and common men. In the late 1800s, the sickness had claimed so many lives in Alabama that it was recorded as the leading cause of death in the state. Despite its seeming invincibility, Alabama health officials, medical practitioners, and civic organizations became committed to eradicating it somehow—or at least minimizing its impact. Over the decades, hopes were elevated by the construction of TB clinics and sanatoriums, aggressive public education programs, and the eventual identification of the disease’s source. By the mid-twentieth century, a vaccine for children at last set the coming generations free and rendered the horrors of “consumption” a relic of darker times. Former Alabama Heritage staff member Alissa Nutting looks at Alabama’s long journey from helplessness to empowerment over the indiscriminate air-borne killer.

Additional Information

The author wishes to thank the Alabama Department of Archives and History for providing invaluable information, in addition to acknowledging the following sources:

- Acts of the General Assembly of the State of Alabama. 14 January, 1919. (The Brown Printing Company, 1919).

- Bardswell, Noel Dean. Advice to Consumptives: Home Treatment, Aftercare, and Prevention. (Black, 1910).

- Blackmon, Douglas A. “From Alabama’s Past, Capitalism Teamed with Racism to Create Cruel Partnership.” Wall Street Journal. 16 July 2001. BRC News.

- Caldwell, Mark. The Last Crusade: The War on Consumption, 1862–1954.(Antheneum, 1988).

- “Death from Neglect.” Author Unlisted. Time. 3 August 1953. .

- Dublin, Louis Israel. A Forty Year Campaign Against Tuberculosis. New York: Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 1952.

- General Laws (and Joint Resolutions) of the Legislature of Alabama.(The Brown Printing Co., 1915).

- Hawes, John B. Consumption: What It Is and What To Do About It. (Small, Maynard & Co., 1916).

- Jacob, Philip P., PhD. A Tuberculosis Directory. (Press of WM. F. Fell Company, 1911).

- Journal of the Outdoor Life: The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine. Volume 14, no. 12. December, 1922.

- Knopf, S. Adolphus, M.D. A History of the National Tuberculosis Association: The Anti-Tuberculosis Movement in the United States. (National Tuberculosis Association, 1922).

- Mancini, Matthew. “Black Prisoners and Their World: 1865–1900.” Alabama Review. University of Alabama Press. October 2002. Proquest Info. and Learning Co.

- “Mortality Patterns: Then and Now.” Health Statistics and Surveillance. Alabama Center for Health Statistics. Vol. 8 No. 2. Alabama Department of Public Health. December 1999.

- Municipal Ordinances, Rules, and Regulations Pertaining to Public Health, 1917–1919. Compiled by Jason Waterman, LLB and William Fowler, LLB. Supplement #40 to the Public Health Reports. Treasury Department, United States Public Health Service. Hugh S. Cumming, Surgeon General. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921.

- Otis, Edward O., M.D. Tuberculosis: Its Cause, Cure, and Prevention. (Thomas Y. Crowell Co. Publishers, 1909).

- Proceedings of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge A.F. & A.M. of Alabama at the One Hundred and Second Annual Communication Held In Montgomery, Alabama, December 6th and 7th, 1922. (The Brown Printing Co., 1923).

- Rammer Jammer. Volume 3, Number 3, 1926. The University of Alabama. Pg. 118.

- Smith, Francis Barrymore. The Retreat of Tuberculosis, 1850–1950. (Croom Helm, 1988).

- South, Jean. Tuberculosis Handbook for Public Health Nurses. (National Tuberculosis Association, 1959).

- Sucre, Richard. “The Great White Plague: The Culture of Death and the Tuberculosis Sanatorium.” University of Virginia.

- Washington, Booker T. Letter to Hartwell Douglas. 9 June 1913. The Booker T. Washington Papers. Louis R. Harland and Raymond W. Smock, Eds. U of Illinois Press. Volume 12, pg. 197–198.

- Woodcock, John H. More Light: A Treatise on Tuberculosis Written Especially for the Negro Race. (Advocate Pub. Co., 1924).

About the Author

Alissa Nutting is a PhD candidate in creative writing and a Schaeffer Fellow in fiction at the University of Nevada—Las Vegas. She received her MFA from the University of Alabama, where she edited the Black Warrior Review literary magazine and served as an assistant editor at Alabama Heritage. Her writing is forthcoming or recently published in magazines such as Denver Quarterly, Fence, and Tin House.

The largest of the five

The largest of the five"Gateway to Anniston" buildings

(Robin McDonald)

Places in Peril 2008: Alabama’s Endangered Historic Landmarks

By Melanie Betz Gregory

The rich history represented in the beautiful, yet crumbling, remains of many historic buildings in Alabama is in perpetual danger of being demolished and erased from memory. In this latest addition of “Places in Peril,” The Alabama Historic Commission, the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation and Alabama Heritage have collaborated to highlight homes, business structures, forts, churches, and schoolhouses that stand at risk from neglect, underfunding, or development. From sites that provide an understanding of Alabama’s colonial beginnings to structures integral to the civil rights movement, these endangered properties tell the Alabama story. With much-needed preservation, these structures will survive to educate, inform, and inspire future generations.

Additional Information

To get involved with Alabama’s Preservation:

Since 1994 the Alabama Historical Commission and the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation have joined forces to sponsor “Places in Peril,” a program that each year highlights some of the state’s significant endangered properties. As awareness yields commitment, and commitment yields action, these endangered properties can be saved and returned to their important place as treasured landmarks.

The “Places in Peril” program has helped to save many important landmarks that might otherwise have been lost. These include the Forks of Cyprus ruins in Florence (listed 1997), the John Glascock House in Tuscaloosa (listed 2001), the Lowe Mill Village in Huntsville (listed 2002), the Coleman House in Uniontown (listed 2003), and Locust Hill in Tuscumbia (listed 2004).

Everyone can play a role to help save those resources that are in peril. Adopt one of the properties. Tell everybody you know that it is important. Write letters of support. Volunteer your time or expertise to the local preservation group. If one of the places really strikes you, go ahead and buy it! A generous (or even modest) donation to the “Endangered Property Trust Fund” can help statewide.

For more information on the fund or joining the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation, call 205-652-3497 or visit them online. For additional information on the “Places in Peril” program, visit the Alabama Historical Commission website or contact Melanie Betz at 334-242-3184.

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Melanie Betz Gregory joined the staff of the Alabama Historical Commission in the fall of 1989. A native of Illinois, she holds a BA in art history from Western Illinois University and an MA in architectural history and historic preservation from the University of Virginia. Gregory is currently working with the AHC Endangered Properties program.

By Melanie Betz Gregory

The rich history represented in the beautiful, yet crumbling, remains of many historic buildings in Alabama is in perpetual danger of being demolished and erased from memory. In this latest addition of “Places in Peril,” The Alabama Historic Commission, the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation and Alabama Heritage have collaborated to highlight homes, business structures, forts, churches, and schoolhouses that stand at risk from neglect, underfunding, or development. From sites that provide an understanding of Alabama’s colonial beginnings to structures integral to the civil rights movement, these endangered properties tell the Alabama story. With much-needed preservation, these structures will survive to educate, inform, and inspire future generations.

Additional Information

To get involved with Alabama’s Preservation:

Since 1994 the Alabama Historical Commission and the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation have joined forces to sponsor “Places in Peril,” a program that each year highlights some of the state’s significant endangered properties. As awareness yields commitment, and commitment yields action, these endangered properties can be saved and returned to their important place as treasured landmarks.

The “Places in Peril” program has helped to save many important landmarks that might otherwise have been lost. These include the Forks of Cyprus ruins in Florence (listed 1997), the John Glascock House in Tuscaloosa (listed 2001), the Lowe Mill Village in Huntsville (listed 2002), the Coleman House in Uniontown (listed 2003), and Locust Hill in Tuscumbia (listed 2004).

Everyone can play a role to help save those resources that are in peril. Adopt one of the properties. Tell everybody you know that it is important. Write letters of support. Volunteer your time or expertise to the local preservation group. If one of the places really strikes you, go ahead and buy it! A generous (or even modest) donation to the “Endangered Property Trust Fund” can help statewide.

For more information on the fund or joining the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation, call 205-652-3497 or visit them online. For additional information on the “Places in Peril” program, visit the Alabama Historical Commission website or contact Melanie Betz at 334-242-3184.

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

- Black Baptists in Alabama

- Selma

- Plantation Architecture in Alabama

- Bloody Sunday

- Selma to Montgomery March

- Amelia Boynton Robinson

- Elba

- James E. ‘Big Jim’ Folsom Sr. (1947-51, 1955-59)

- Chambers County

- Lowndes County

- St. Clair County

- Folk Buildings

- Anniston

- James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

- Lowndes County School

- Lowndes County Schoolhouse

- Ensley Company Steel Production

- Downtown Anniston

About the Author

Melanie Betz Gregory joined the staff of the Alabama Historical Commission in the fall of 1989. A native of Illinois, she holds a BA in art history from Western Illinois University and an MA in architectural history and historic preservation from the University of Virginia. Gregory is currently working with the AHC Endangered Properties program.

To read about more places in peril, click here for our Places in Peril blog.

DEPARTMENT ABSTRACTS

An M&O Railroad ice house

An M&O Railroad ice house(National Archives & Records

Administration)

Southern Architecture and Preservation

The Workaday Alabama Landscape

By W. Andrew Waldo

While perusing collections at the National Archives, Andrew Waldo encountered a remarkable treasure. In an early twentieth-century project to inventory the holdings of U. S. railroad companies, thousands of photographs documenting the “workaday” life near the tracks were captured and are now stored and available to the public. In this brief photographic piece, Waldo provides a “sneak peek” at what this archival wonder holds for the lovers of Alabama history.

Additional Information

To get involved with Alabama’s Preservation:

Since 1994 the Alabama Historical Commission and the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation have joined forces to sponsor “Places in Peril,” a program that each year highlights some of the state’s significant endangered properties. As awareness yields commitment, and commitment yields action, these endangered properties can be saved and returned to their important place as treasured landmarks.

The “Places in Peril” program has helped to save many important landmarks that might otherwise have been lost. These include the Forks of Cyprus ruins in Florence (listed 1997), the John Glascock House in Tuscaloosa (listed 2001), the Lowe Mill Village in Huntsville (listed 2002), the Coleman House in Uniontown (listed 2003), and Locust Hill in Tuscumbia (listed 2004).

Everyone can play a role to help save those resources that are in peril. Adopt one of the properties. Tell everybody you know that it is important. Write letters of support. Volunteer your time or expertise to the local preservation group. If one of the places really strikes you, go ahead and buy it! A generous (or even modest) donation to the “Endangered Property Trust Fund” can help statewide.

For more information on the fund or joining the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation, call 205-652-3497 or visit them online. For additional information on the “Places in Peril” program, visit the Alabama Historical Commission website or contact Melanie Betz at 334-242-3184.

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

About the Author

W. Andrew Waldo, formerly of Montgomery, is now an Episcopal priest serving a church in Minnesota. Robert Gamble and Melanie Betz Gregory, architectural historians for the Alabama Historical Commission, serve as the standing editors of the “Southern Architecture and Preservation” department of Alabama Heritage.

The Workaday Alabama Landscape

By W. Andrew Waldo

While perusing collections at the National Archives, Andrew Waldo encountered a remarkable treasure. In an early twentieth-century project to inventory the holdings of U. S. railroad companies, thousands of photographs documenting the “workaday” life near the tracks were captured and are now stored and available to the public. In this brief photographic piece, Waldo provides a “sneak peek” at what this archival wonder holds for the lovers of Alabama history.

Additional Information

To get involved with Alabama’s Preservation:

Since 1994 the Alabama Historical Commission and the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation have joined forces to sponsor “Places in Peril,” a program that each year highlights some of the state’s significant endangered properties. As awareness yields commitment, and commitment yields action, these endangered properties can be saved and returned to their important place as treasured landmarks.

The “Places in Peril” program has helped to save many important landmarks that might otherwise have been lost. These include the Forks of Cyprus ruins in Florence (listed 1997), the John Glascock House in Tuscaloosa (listed 2001), the Lowe Mill Village in Huntsville (listed 2002), the Coleman House in Uniontown (listed 2003), and Locust Hill in Tuscumbia (listed 2004).

Everyone can play a role to help save those resources that are in peril. Adopt one of the properties. Tell everybody you know that it is important. Write letters of support. Volunteer your time or expertise to the local preservation group. If one of the places really strikes you, go ahead and buy it! A generous (or even modest) donation to the “Endangered Property Trust Fund” can help statewide.

For more information on the fund or joining the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation, call 205-652-3497 or visit them online. For additional information on the “Places in Peril” program, visit the Alabama Historical Commission website or contact Melanie Betz at 334-242-3184.

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

- Stevenson Railroad Depot

- Cullman Railroad Depot

- Frisco Railroad in Walker County, ca. 1914

- Tuscumbia Depot/Museum

- Southern Railway Advertisement

About the Author

W. Andrew Waldo, formerly of Montgomery, is now an Episcopal priest serving a church in Minnesota. Robert Gamble and Melanie Betz Gregory, architectural historians for the Alabama Historical Commission, serve as the standing editors of the “Southern Architecture and Preservation” department of Alabama Heritage.

The author and her sisters and cousins

The author and her sisters and cousins(Jane Kilgore Hinton)

Recollections

Cedar Cove: A Town That Disappeared

By Aileen Kilgore Henderson

Of all the places that have been torn down and nearly forgotten in Tuscaloosa County, the lost coal mining town of Cedar Cove remains one of the most enigmatic, as only a pair of tombstones remained to mark its location as late as 1973. Now even those are missing. Built in 1916 on the site of the Reed Plantation cemetery, the town was sustained by tight-knit families, community-mindedness, fun, games, hard work, coal dust, and hot baths. Cedar Cove thrived until the Great Depression forced these proud Alabamians to disperse, leaving their beloved town to be scrapped, plowed over, and all but forgotten. Aileen Henderson reflects on daily life in the small mining camp that seemed like a palace to her as a small girl.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Aileen Kilgore Henderson, author of numerous books and articles, was born in Cedar Cove and now lives in Brookwood.

Cedar Cove: A Town That Disappeared

By Aileen Kilgore Henderson

Of all the places that have been torn down and nearly forgotten in Tuscaloosa County, the lost coal mining town of Cedar Cove remains one of the most enigmatic, as only a pair of tombstones remained to mark its location as late as 1973. Now even those are missing. Built in 1916 on the site of the Reed Plantation cemetery, the town was sustained by tight-knit families, community-mindedness, fun, games, hard work, coal dust, and hot baths. Cedar Cove thrived until the Great Depression forced these proud Alabamians to disperse, leaving their beloved town to be scrapped, plowed over, and all but forgotten. Aileen Henderson reflects on daily life in the small mining camp that seemed like a palace to her as a small girl.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

- Tuscaloosa County

- Mining Labor

- Public Education in the Early Twentieth Century

- Coal Mining

- Industrial Baseball Leagues in Alabama

About the Author

Aileen Kilgore Henderson, author of numerous books and articles, was born in Cedar Cove and now lives in Brookwood.

Carl Sloan splits shale

Carl Sloan splits shale(L.J. Davenport)

Nature Journal

Union Chapel Mine: Or, When Salamanders Slimed the Earth

By Larry Davenport

Several million years ago, prehistoric reptilian creatures slithered in the shallow surf covering much of what is now central Alabama. The footprints etched into sandy beaches, the fossils of organisms long extinct, and even the curving trails where fish tails grazed the shallow sandy bottom are forever preserved in sheets of gray shale fortuitously unearthed by strip mining. Dr. Larry Davenport chronicles the efforts of a team of scientists who visited Union Chapel Mine to search for relics of Alabama’s primeval past—evidence of the salamanders that slimed the earth.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

Union Chapel Mine: Or, When Salamanders Slimed the Earth

By Larry Davenport

Several million years ago, prehistoric reptilian creatures slithered in the shallow surf covering much of what is now central Alabama. The footprints etched into sandy beaches, the fossils of organisms long extinct, and even the curving trails where fish tails grazed the shallow sandy bottom are forever preserved in sheets of gray shale fortuitously unearthed by strip mining. Dr. Larry Davenport chronicles the efforts of a team of scientists who visited Union Chapel Mine to search for relics of Alabama’s primeval past—evidence of the salamanders that slimed the earth.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

- Amphibian Footprints

- Fish Fin Trail

- Abrupt Turn in Amphibian Trackway

- Millipede Trackway

- Multiple Horseshoe Crab Trackways

- Fossils (Gallery)

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

Reading the Southern Past

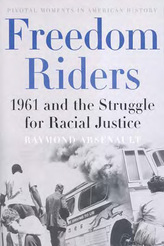

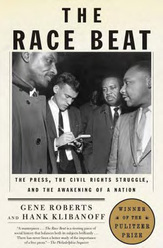

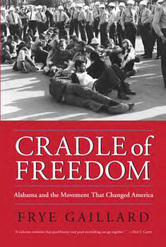

Freedom Riders, the Race Beat, and Alabama

By Stephen Goldfarb

At the height of the civil rights movement, numerous groups and individuals worked to advance the cause. In this latest addition to “Reading the Southern Past,” Stephen Goldfarb reviews three books that chronicle these efforts. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice by Raymond Arsenault (Oxford University Press, 2006) explores the people who traveled—often at great risk—the interstates of the South, registering black voters and defying the segregation of public transportation. The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation by Gene Roberts and Hank Kilbanoff (Alfred A. Knopf, 2007) explores the role of news journalists in the movement. And Frye Gaillard’s Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement That Changed America (University of Alabama Press, 2004) describes the epicenter of the civil rights showdown of the 1960s—the towns and cities of Alabama.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Stephen Goldfarb holds a PhD in the history of science and technology. He retired from a public library in 2003.

Freedom Riders, the Race Beat, and Alabama

By Stephen Goldfarb

At the height of the civil rights movement, numerous groups and individuals worked to advance the cause. In this latest addition to “Reading the Southern Past,” Stephen Goldfarb reviews three books that chronicle these efforts. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice by Raymond Arsenault (Oxford University Press, 2006) explores the people who traveled—often at great risk—the interstates of the South, registering black voters and defying the segregation of public transportation. The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation by Gene Roberts and Hank Kilbanoff (Alfred A. Knopf, 2007) explores the role of news journalists in the movement. And Frye Gaillard’s Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement That Changed America (University of Alabama Press, 2004) describes the epicenter of the civil rights showdown of the 1960s—the towns and cities of Alabama.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

- Freedom Riders

- Modern Civil Rights Movement in Alabama

- Segregation (Jim Crow)

- Bloody Sunday

- The Civil Rights Movement in Alabama (feature)

- Freedom Riders

- Attack on Freedom Riders, 1961

- Freedom Riders Arrested in Birmingham

- Segregated Streetcar

- Marching to Montgomery

About the Author

Stephen Goldfarb holds a PhD in the history of science and technology. He retired from a public library in 2003.