|

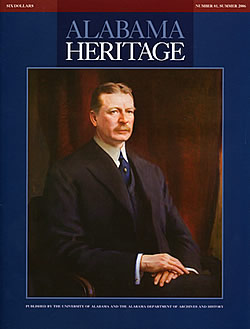

On the cover: Portrait of Alabama Power Company founder James Mitchell by Danish-born American Impressionist John Christen Johansen (1876-1944).

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

James Mitchell

James Mitchell(James Mitchell Family)

Empowering Alabama: The James Mitchell Story

By Leah Rawls Atkins

Engineer and entrepreneur James Mitchell was passionate about the potential of hydroelectric power. Chronicled here are his efforts to bring reliable electricity to Alabama by exploiting the state’s expansive river system. Mitchell invested much of his career and a substantial portion of his own capital to build hydroelectric dams that would support the new Alabama Power Company. Not terribly interested in fiscal profit, Mitchell succeeded in his greater goal: to leave a legacy—“A new Alabama and a new South.”

Additional Information

Multimedia:

About the Author

Leah Rawls Atkins, director emeritus of the Auburn University Center for the Arts & Humanities, holds a Ph.D. from Auburn University and taught history for almost three decades at Auburn and Samford Universities. She is a co-author of the award-winning Alabama: The History of a Deep South State, which was published by the University of Alabama Press in 1994. She retired in 1995, and since then has written a biography of John M. Harbert III, a corporate history of Brasfield & Gorrie, and is currently completing the centennial history of the Alabama Power Company, which will be published in late 2006. She lives in Birmingham.

By Leah Rawls Atkins

Engineer and entrepreneur James Mitchell was passionate about the potential of hydroelectric power. Chronicled here are his efforts to bring reliable electricity to Alabama by exploiting the state’s expansive river system. Mitchell invested much of his career and a substantial portion of his own capital to build hydroelectric dams that would support the new Alabama Power Company. Not terribly interested in fiscal profit, Mitchell succeeded in his greater goal: to leave a legacy—“A new Alabama and a new South.”

Additional Information

- Atkins, Leah Rawls.Developed for the Service of Alabama: The Centennial History of the Alabama Power Company (Alabama Power Company, 2006).

- Martin, Thomas W. The Story of Electricity in Alabama. (Birmingham Publishing Company, 1952)

Multimedia:

About the Author

Leah Rawls Atkins, director emeritus of the Auburn University Center for the Arts & Humanities, holds a Ph.D. from Auburn University and taught history for almost three decades at Auburn and Samford Universities. She is a co-author of the award-winning Alabama: The History of a Deep South State, which was published by the University of Alabama Press in 1994. She retired in 1995, and since then has written a biography of John M. Harbert III, a corporate history of Brasfield & Gorrie, and is currently completing the centennial history of the Alabama Power Company, which will be published in late 2006. She lives in Birmingham.

The home of Harry Toulmin,

The home of Harry Toulmin,now Alumni Hall at the University of South Alabama

(University of South Alabama Archives)

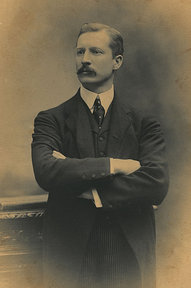

Toulmin & Hitchcock, Pioneering Jurists of the Alabama Frontier

By Philip Beidler

Amid the freewheeling and often lawless atmosphere of Alabama’s territorial and early statehood eras, Harry Toulmin and Henry Hitchcock authored two landmark legal volumes. Toulmin, the son of a noted theologian and a disciple of Dr. Joseph Priestly, wrote A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama, an important legal compendium that would help codify the laws and democratize the state legal system. Henry Hitchcock, a descendent of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, authored Alabama Justice of the Peace, a guidebook and courts manual that soon became the standard text for judicial functionaries on the outposts of the frontier.

By Philip Beidler

Amid the freewheeling and often lawless atmosphere of Alabama’s territorial and early statehood eras, Harry Toulmin and Henry Hitchcock authored two landmark legal volumes. Toulmin, the son of a noted theologian and a disciple of Dr. Joseph Priestly, wrote A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama, an important legal compendium that would help codify the laws and democratize the state legal system. Henry Hitchcock, a descendent of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, authored Alabama Justice of the Peace, a guidebook and courts manual that soon became the standard text for judicial functionaries on the outposts of the frontier.

Additional Information

About the Author

Philip Beidler is a professor of English at the University of Alabama, where he has taught American literature since receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Virginia in 1974. His publications over the years in Alabama Heritage include essays on Caroline Lee Hentz, Johnny Mack Brown, and Alabama soldiers in the Vietnam War and the American Civil War. His most recent book is Late Thoughts on an Old War: The Legacy of Vietnam (2004). He has just completed a new set of linked essays on American wars and American peace, Son of the Empire.

Errata

There are a couple of errors in the article entitled “Toulmin & Hitchcock: Pioneering Jurists of the Alabama Frontier.” A descendent of Harry Toulmin has notified us that the often-published death date of 1824 for Toulmin is incorrect. He died in 1823. Also the photograph identified as “the home of Harry Toulmin” is actually the home of his son. We are in search of a photograph of Toulmin’s last home and will post it online when we find it.

- Alabama Department of Archives & History Bio of Henry Hitchcock

- Alabama Supreme Court & State Law Library

- DeNeefe, Janie. “Lessons taught by ancestor still relevant to citizens today” The Huntsville Times, April 30, 2006. Harry Toulmin’s descendant.

- Ethan Allen Homestead History

- Hitchcock, Henry. Alabama Justice of the Peace

- Toulmin, Harry. A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama

- Toulmin, Llewellyn M. “Ancestral Journey” The Mobile Register March 19, 2006. Another descendant.

- Henry Hitchcock

- Henry Hitchcock (image)

- Territorial Period and Early Statehood

- U.S. District Courts in Alabama

About the Author

Philip Beidler is a professor of English at the University of Alabama, where he has taught American literature since receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Virginia in 1974. His publications over the years in Alabama Heritage include essays on Caroline Lee Hentz, Johnny Mack Brown, and Alabama soldiers in the Vietnam War and the American Civil War. His most recent book is Late Thoughts on an Old War: The Legacy of Vietnam (2004). He has just completed a new set of linked essays on American wars and American peace, Son of the Empire.

Errata

There are a couple of errors in the article entitled “Toulmin & Hitchcock: Pioneering Jurists of the Alabama Frontier.” A descendent of Harry Toulmin has notified us that the often-published death date of 1824 for Toulmin is incorrect. He died in 1823. Also the photograph identified as “the home of Harry Toulmin” is actually the home of his son. We are in search of a photograph of Toulmin’s last home and will post it online when we find it.

This hand-painted wallpaper by an anonymous artist depicts a pastoral fantasy of the mythic Aigleville

This hand-painted wallpaper by an anonymous artist depicts a pastoral fantasy of the mythic Aigleville(Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Alabama's Vine and Olive Colony: Myth and Fact

By Rafe Blaufarb

In the legend of the Vine and Olive Colony, a group of French military aristocrats fled to Alabama in 1817 after their Emperor Napoleon was deposed, and tried to cultivate grape vines and olive trees while maintaining their lavish lifestyle in Marengo County. In reality, most of the settlers were refugees from the French Caribbean island of St. Domingue where a bloody slave rebellion had left thousands dead. Congress approved a bill that gave the French settlers ninety-two thousand acres of recently conquered Creek and Choctaw territory before the lands were offered to the general public. Although bombarded with criticism over this generous “gift,” Congress created the land grant as part of a strategy to solidify the United States’ hold on the Gulf Coast by populating the area. A prime location at the juncture of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers—navigable rivers that flowed into Mobile Bay—also made the colony important. The struggle for basic survival overshadowed attempts to grow grape vines and olive trees, and by 1831 the colonists were released from obligations to plant the area with vines and olives. Although not a success in viticulture, the Vine and Olive Colony did make a lasting impact on future westward expansion. Congress would never again make a similar grant, so expansion had to be carried out in a more individualistic way.

By Rafe Blaufarb

In the legend of the Vine and Olive Colony, a group of French military aristocrats fled to Alabama in 1817 after their Emperor Napoleon was deposed, and tried to cultivate grape vines and olive trees while maintaining their lavish lifestyle in Marengo County. In reality, most of the settlers were refugees from the French Caribbean island of St. Domingue where a bloody slave rebellion had left thousands dead. Congress approved a bill that gave the French settlers ninety-two thousand acres of recently conquered Creek and Choctaw territory before the lands were offered to the general public. Although bombarded with criticism over this generous “gift,” Congress created the land grant as part of a strategy to solidify the United States’ hold on the Gulf Coast by populating the area. A prime location at the juncture of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers—navigable rivers that flowed into Mobile Bay—also made the colony important. The struggle for basic survival overshadowed attempts to grow grape vines and olive trees, and by 1831 the colonists were released from obligations to plant the area with vines and olives. Although not a success in viticulture, the Vine and Olive Colony did make a lasting impact on future westward expansion. Congress would never again make a similar grant, so expansion had to be carried out in a more individualistic way.

Additional Information

Multimedia:

About the Author

Rafe Blaufarb, Associate Professor at Auburn University, is a specialist in French history, 1530–1830, with thematic interests in military history, the history of the state, and the Age of Revolution in the Atlantic world. He received his B.A. from Amherst College in 1985 and his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in 1996. His first book, The French Army, 1750 – 1820: Careers, Talent, Merit (Manchester, 2002), treats the meritocratic transformation of the French military profession across the revolutionary period. His second book, Bonapartists in the Borderlands: French Exiles and Refugees on the Gulf Coast, 1815 – 1835, on the French settlement in territorial Alabama known as the Vine and Olive Colony, was published by the University of Alabama Press in 2006. His current research is on state centralization, taxation, and social conflict in early modern France, 1530–1789 and on the impact of Latin American independence in the broader Atlantic world.

- Blaufarb, Rafe. Bonapartists in the Borderlands (University of Alabama Press, 2006). [Amazon.com]

- Charles Lallemand, Texas Handbook

- History of Demopolis

- Marengo County Historical Markers

Multimedia:

About the Author

Rafe Blaufarb, Associate Professor at Auburn University, is a specialist in French history, 1530–1830, with thematic interests in military history, the history of the state, and the Age of Revolution in the Atlantic world. He received his B.A. from Amherst College in 1985 and his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in 1996. His first book, The French Army, 1750 – 1820: Careers, Talent, Merit (Manchester, 2002), treats the meritocratic transformation of the French military profession across the revolutionary period. His second book, Bonapartists in the Borderlands: French Exiles and Refugees on the Gulf Coast, 1815 – 1835, on the French settlement in territorial Alabama known as the Vine and Olive Colony, was published by the University of Alabama Press in 2006. His current research is on state centralization, taxation, and social conflict in early modern France, 1530–1789 and on the impact of Latin American independence in the broader Atlantic world.

Lucille Douglass

Lucille Douglass (Birmingham Public Library

Archives)

From Tuskegee to Angkor: The Odyssey of Lucille Douglass

By Stephen Goldfarb

In an era when women were expected to be dainty, passive, and entertaining, Lucille Douglass was an exception. Born into the genteel poverty of Tuskegee, Alabama in 1878, Douglass learned the foundations of visual art from her mother and yearned for travel. She graduated college with an art degree at the age of seventeen, and soon moved to Birmingham, where she lived alone for several years as both an artist and art teacher in a loft above the city. There she banded with other female artists to found the Birmingham Art Club—a foundation that still exists today. In 1909 Douglass turned her childhood dreams of travel into a European odyssey of artistic training, studying with masters like Rene Menard, Lucien Simon, and Alexander Robinson. She spent the rest of her life trotting the globe, working her way from Paris to Shanghai, to Angkor–even to parts of Africa. Everywhere she went, Douglass preserved her encounters as works of art. Through her paintings, etchings, and pastel drawings, she captured the exotic, and made it accessible to those not privileged enough to experience it firsthand.

By Stephen Goldfarb

In an era when women were expected to be dainty, passive, and entertaining, Lucille Douglass was an exception. Born into the genteel poverty of Tuskegee, Alabama in 1878, Douglass learned the foundations of visual art from her mother and yearned for travel. She graduated college with an art degree at the age of seventeen, and soon moved to Birmingham, where she lived alone for several years as both an artist and art teacher in a loft above the city. There she banded with other female artists to found the Birmingham Art Club—a foundation that still exists today. In 1909 Douglass turned her childhood dreams of travel into a European odyssey of artistic training, studying with masters like Rene Menard, Lucien Simon, and Alexander Robinson. She spent the rest of her life trotting the globe, working her way from Paris to Shanghai, to Angkor–even to parts of Africa. Everywhere she went, Douglass preserved her encounters as works of art. Through her paintings, etchings, and pastel drawings, she captured the exotic, and made it accessible to those not privileged enough to experience it firsthand.

Additional Information

The longest and most complete account of Douglass’s life and career can be found in Vicki Leigh Ingham, Art of the New South: Women Artists of Birmingham, 1890–1950 (Birmingham Historical Society, 2004). An episode in Douglass’s career not dealt with in this article can be found in Catherine MacKenzie, “Florence Wheelock Ayscough’s Niger Reef Tea House,”Journal of Canadian Art History/Annales d’Histoire de l’Art Canadien, 23 (2002), 34-62. The Birmingham Museum of Art has extensive holdings of Douglass’s art, mostly from before World War I (and a few papers) and the Department of Archives and Manuscripts of the Birmingham Public Library has extensive holdings of Douglass’s papers.

For possible further study, the author would like to hear from anyone who owns any of Miss Douglass’s papers or art works, especially her paintings. He can be reached via email.

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Stephen J. Goldfarb holds a Ph.D. in the history of science and technology from Case Western Reserve University. He retired from the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library in 2003. His article on the Mobile etcher/artist Marian Acker Macpherson appeared inAlabama Heritage, # 73, Summer 2004. He has also written on New Deal art (primarily post office murals) in Georgia.

Errata

On page 41 in “From Tuskegee to Angkor: The Odyssey of Lucille Douglass,” the phrase “HMS Titanic” should have read, “RMS Titanic.”

The longest and most complete account of Douglass’s life and career can be found in Vicki Leigh Ingham, Art of the New South: Women Artists of Birmingham, 1890–1950 (Birmingham Historical Society, 2004). An episode in Douglass’s career not dealt with in this article can be found in Catherine MacKenzie, “Florence Wheelock Ayscough’s Niger Reef Tea House,”Journal of Canadian Art History/Annales d’Histoire de l’Art Canadien, 23 (2002), 34-62. The Birmingham Museum of Art has extensive holdings of Douglass’s art, mostly from before World War I (and a few papers) and the Department of Archives and Manuscripts of the Birmingham Public Library has extensive holdings of Douglass’s papers.

For possible further study, the author would like to hear from anyone who owns any of Miss Douglass’s papers or art works, especially her paintings. He can be reached via email.

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

- Adelaide Mahan

- Adelaide Mahan (gallery)

About the Author

Stephen J. Goldfarb holds a Ph.D. in the history of science and technology from Case Western Reserve University. He retired from the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library in 2003. His article on the Mobile etcher/artist Marian Acker Macpherson appeared inAlabama Heritage, # 73, Summer 2004. He has also written on New Deal art (primarily post office murals) in Georgia.

Errata

On page 41 in “From Tuskegee to Angkor: The Odyssey of Lucille Douglass,” the phrase “HMS Titanic” should have read, “RMS Titanic.”

DEPARTMENT ABSTRACTS

Two patrons

Two patrons at the fieldstone bar in Bangor Cave

(Blount County

Memorial Museum)

Alabama Mysteries

Bangor Cave Casino

By Pam Jones

In the summer of 1937, J. Breck Musgrove and fellow investors opened Alabama’s only underground nightclub. This nightclub occupied the front caverns of Bangor Cave in Blount County, and no expense was spared to make it into a lavish (and illegal) destination. Governor Bibb Graves ordered the club, along with other “notorious dives,” closed down. But a few government raids couldn’t keep the Bangor Cave Club from being a huge success. In its heyday, the club attracted dancers, diners, gamblers, and criminals to its secret luxury, but now all that remains is a community of cave creatures and some dim outlines of a bar and orchestra pit.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:Multimedia:

About the Author

Pamela Jones is a freelance writer and researcher based in Birmingham.

Bangor Cave Casino

By Pam Jones

In the summer of 1937, J. Breck Musgrove and fellow investors opened Alabama’s only underground nightclub. This nightclub occupied the front caverns of Bangor Cave in Blount County, and no expense was spared to make it into a lavish (and illegal) destination. Governor Bibb Graves ordered the club, along with other “notorious dives,” closed down. But a few government raids couldn’t keep the Bangor Cave Club from being a huge success. In its heyday, the club attracted dancers, diners, gamblers, and criminals to its secret luxury, but now all that remains is a community of cave creatures and some dim outlines of a bar and orchestra pit.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:Multimedia:

About the Author

Pamela Jones is a freelance writer and researcher based in Birmingham.

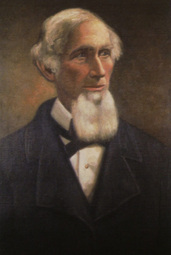

Josiah Clark Nott

Josiah Clark Nott (UAB Historical Collections

University of Alabama

at Birmingham)

Nature Journal

The Two Faces of Dr. Nott

By L. J. Davenport

Dr. Josiah Nott settled in Mobile in 1837 and quickly established a successful medical practice in that city. Mobile frequently was visited by epidemics of yellow fever, and Nott helped treat many afflicted citizens. In an 1848 article, Nott declared his radical beliefs that yellow fever was different from other tropical fevers and that an insect must be involved in the spreading of the disease. Alas, these findings about yellow fever were not the Nott ideas to be embraced by the public. Instead, the ideas that got the most attention were Nott’s “scientific” theories supporting slavery.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:Multimedia:

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

The Two Faces of Dr. Nott

By L. J. Davenport

Dr. Josiah Nott settled in Mobile in 1837 and quickly established a successful medical practice in that city. Mobile frequently was visited by epidemics of yellow fever, and Nott helped treat many afflicted citizens. In an 1848 article, Nott declared his radical beliefs that yellow fever was different from other tropical fevers and that an insect must be involved in the spreading of the disease. Alas, these findings about yellow fever were not the Nott ideas to be embraced by the public. Instead, the ideas that got the most attention were Nott’s “scientific” theories supporting slavery.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:Multimedia:

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

Gold Star Pilgrims at the

Gold Star Pilgrims at theFlanders Field American Cemetery

(Michael Kearney

in honor of Thomas Emmett Kearney)

Recollections:

A Gold Star Pilgrimage to Flanders Fields

By J. Darren Peterson

Among the 368 graves in the Flanders Field American Cemetery in Waregem, Belgium rests Pvt. William C. Barlow of Ashford— the only native Alabamian buried there. In spite of an attempt to be exempted due to “dependent parents,” Barlow was drafted on April 20, 1918. Newly married, he spent only five days with his bride before being called to duty. Barlow’s widow chose to have him laid to rest close to where he fell instead of bringing his body back to Alabama. In 1931, thanks to the Gold Star Pilgrimages program, Barlow’s mother and sister were able to visit the grave at last.

Additional Information

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

A native of Alabama's Wiregrass region, J. Darren Peterson is a software engineer with a deep interest in history.

A Gold Star Pilgrimage to Flanders Fields

By J. Darren Peterson

Among the 368 graves in the Flanders Field American Cemetery in Waregem, Belgium rests Pvt. William C. Barlow of Ashford— the only native Alabamian buried there. In spite of an attempt to be exempted due to “dependent parents,” Barlow was drafted on April 20, 1918. Newly married, he spent only five days with his bride before being called to duty. Barlow’s widow chose to have him laid to rest close to where he fell instead of bringing his body back to Alabama. In 1931, thanks to the Gold Star Pilgrimages program, Barlow’s mother and sister were able to visit the grave at last.

Additional Information

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

A native of Alabama's Wiregrass region, J. Darren Peterson is a software engineer with a deep interest in history.