|

On the cover: Tea-servers kept Chinese laborers in Reconstruction Alabama supplied with their favorite beverage. (Courtesy The Historical New Orleans Collection, Museum/Research Center, Acc. No. 1953.80. Tinting by Jan Pruitt)

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

Chinese Laborers in Reconstruction Alabama

By Daniel Liestman

In the years following the Civil War, Alabama embarked on what some called "the Chinese experiment." For the experiment's most optimistic proponents, the idea was simple and sure: Import inexpensive Chinese workers to redress the dire labor shortages the state was suffering after the Civil War and use Chinese immigrants to rebuild plantations and to construct railroads, thereby resuscitating the state's lifeless post-war economy at the least possible cost. For the most part, the plan did not work. In this article, Daniel Liestman examines the plan, the thinking behind it, and the reasons for its failure.

Additional Information

About the Author

Daniel Liestman, reference librarian and coordinator of bibliographic instruction, the Kilmer Area Library, Rutgers University, holds master's degrees in library science (University of Tennessee) and history (Midwestern State University, Texas). A native of Wisconsin, Liestman spent his undergraduate years in South Dakota, where he became interested in Chinese immigration to the United States. "The Yellow Man in the Black Hills," an article by Liestman on the Chinese in nineteenth-century South Dakota, was published in the Journal of the West in January 1988. From August 1985 to January 1988, Liestman was a reference librarian at the Amelia Gayle Gorgas Library, University of Alabama.

By Daniel Liestman

In the years following the Civil War, Alabama embarked on what some called "the Chinese experiment." For the experiment's most optimistic proponents, the idea was simple and sure: Import inexpensive Chinese workers to redress the dire labor shortages the state was suffering after the Civil War and use Chinese immigrants to rebuild plantations and to construct railroads, thereby resuscitating the state's lifeless post-war economy at the least possible cost. For the most part, the plan did not work. In this article, Daniel Liestman examines the plan, the thinking behind it, and the reasons for its failure.

Additional Information

- Barth, Gunther. Bitter Strength: A History of the Chinese in the United States, 1850-1870 (Harvard University Press, 1974).

- Clark, James Harold. "History of the North-East and South-West Alabama Railroad to 1872," M.A. thesis, University of Alabama, 1949.

- Cohen, Lucy M. Chinese in the Post-Civil War South: A People Without a History (Louisiana State University Press, 1984).

- _____. "Entry of Chinese to the Lower South from 1865 to 1870: Policy Dilemmas," Southern Studies, 17 {Spring 1978): 5-37.

- Krebs, Sylvia H. "John Chinaman and Reconstruction Alabama: The Debate and the Experience," Southern Studies, 21 (Winter 1982): 369-83.

- Miller, Stuart Creighton. The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the Chinese, 1875-1882 (University of California Press, 1%9).

- Peabody, Etta B. "Efforts of the South to Import Chinese Coolies, 1865-1870," M.A. thesis, Baylor University, 1967.

About the Author

Daniel Liestman, reference librarian and coordinator of bibliographic instruction, the Kilmer Area Library, Rutgers University, holds master's degrees in library science (University of Tennessee) and history (Midwestern State University, Texas). A native of Wisconsin, Liestman spent his undergraduate years in South Dakota, where he became interested in Chinese immigration to the United States. "The Yellow Man in the Black Hills," an article by Liestman on the Chinese in nineteenth-century South Dakota, was published in the Journal of the West in January 1988. From August 1985 to January 1988, Liestman was a reference librarian at the Amelia Gayle Gorgas Library, University of Alabama.

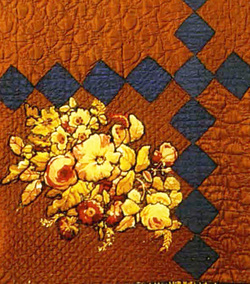

A detail of quilt made prior to 1862 by

A detail of quilt made prior to 1862 by Martha Jane Hatter of Greensboro, Alabama.

(Photo courtesy Chip Cooper)

Gunboat Quilts

By Bryding Adams Henley

In mid-February 1862, the Mobile Register and Advertiser published a letter from "A Southern Woman" who wished to appeal to the patriotism of Southern women in general and Alabama women in particular, all of whom, she said, should begin raising money for the cause of the Confederacy. This particular Southern woman had as her goal the creation of a gunboat to defend the City of Mobile. To this end, the woman was willing to contribute "her mite of less than five dollars" which she had "earned by her needle." Thus began the inspiration for a statewide campaign in Alabama to raise money for what came to be known as the Women's Gunboat Fund.

Additional Information

About the Author

Bryding Henley, curator of decorative arts at the Birmingham Museum of Art, received a bachelor's degree in art history from Hollins College and a master's degree in museum studies from the Cooperstown Graduate Program in New York. A native of Alabama, she returned home eight years ago with plans to undertake a statewide research project designed to locate, identify, and document nineteenth- and early twentieth-century decorative arts in Alabama. That study, the

Alabama Decorative Arts Survey, is now in its third year, and this article represents a small part of the findings of that survey.

Ms. Henley is currently researching the nineteenth-century Alabama folk artist, William Frye. Persons with paintings by Frye and information about his life are asked to contact her at the Birmingham Museum of Art, 2000 Eighth Avenue North, Birmingham, Alabama 35203; (205) 254-2565.

By Bryding Adams Henley

In mid-February 1862, the Mobile Register and Advertiser published a letter from "A Southern Woman" who wished to appeal to the patriotism of Southern women in general and Alabama women in particular, all of whom, she said, should begin raising money for the cause of the Confederacy. This particular Southern woman had as her goal the creation of a gunboat to defend the City of Mobile. To this end, the woman was willing to contribute "her mite of less than five dollars" which she had "earned by her needle." Thus began the inspiration for a statewide campaign in Alabama to raise money for what came to be known as the Women's Gunboat Fund.

Additional Information

- Cargo, Robert, Gail C. Andrews, and Janet Strain McDonald. Black Belt to Hill Country: Alabama Quilts from the Robert and Helen Cargo Collection (Birmingham Museum of Art, 1982).

- Horton, Laurel. "South Carolina Quilts in the Civil War," in Uncoverings 1985, edited by Sally Garoutte (American Quilt Study Group, 1986).

- Horton, Laurel and Lynn Robertson Myers, eds. Social Fabric: South Carolina 's Traditional Quilts (McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, no date).

- Newman, Joyce Joines. North Carolina Country Quilts (The Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1978).

- Still, William N., Jr. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1971).

About the Author

Bryding Henley, curator of decorative arts at the Birmingham Museum of Art, received a bachelor's degree in art history from Hollins College and a master's degree in museum studies from the Cooperstown Graduate Program in New York. A native of Alabama, she returned home eight years ago with plans to undertake a statewide research project designed to locate, identify, and document nineteenth- and early twentieth-century decorative arts in Alabama. That study, the

Alabama Decorative Arts Survey, is now in its third year, and this article represents a small part of the findings of that survey.

Ms. Henley is currently researching the nineteenth-century Alabama folk artist, William Frye. Persons with paintings by Frye and information about his life are asked to contact her at the Birmingham Museum of Art, 2000 Eighth Avenue North, Birmingham, Alabama 35203; (205) 254-2565.

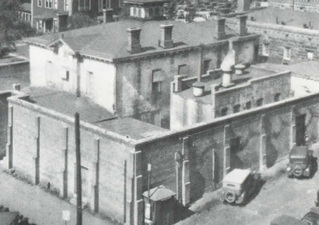

The Jefferson County Jail, known as "The Rock," housed

The Jefferson County Jail, known as "The Rock," housed many of the most dangerous prisoners from Bibb and

surrounding counties until it was razed in 1927. (Courtesy

Birmingham Public Library)

Outlaws, Cat's-Paws, and Spotters

By Rhoda Coleman Ellison

A century ago, crime flourished in the central Alabama backwoods. Thieves made their raids from the rough hill country, afterwards retiring safely among protective family and friends. Their primary object was to seize livestock and cotton, but theft sometimes led to violence. The press followed the exploits of these desperadoes avidly and heaped condemnation on those counties that failed to control them. By the early 1890s, Bibb County bore the heaviest burden of shame. It was known as "Bloody Bibb." And yet, from time to time throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Bibb's neighboring counties were bloody, too. Besides producing criminals of their own, they were havens for others who operated without any respect for county lines. This article recounts the exploits of some of these criminals.

Additional Information

About the Author

Rhoda Coleman Ellison, whose article "Little Italy in Rural Alabama" [Alabama Heritage #2, Fall1986] remains one of the most frequently requested articles Alabama Heritage has published, has again tapped the rich resources of her native Bibb County. For this article on nineteenth-century outlaws, Ellison combed the newspapers of the period and interviewed descendants of many of the people involved. Indeed, Ellison's own life touches her article indirectly. In 1892, when her father came as a young man to practice law in Bibb County, he disembarked at the Randolph train station, where Wiley Trott had shot the Louisiana sheriff a year earlier. Ellison believes her father was present at Trott's

trial the day Trott attempted to cut his own throat with a pen knife.

The author would like to thank the following individuals who provided information for the article: John Glasscock, Jemison; Charles Adams, Tuscaloosa; Melvin Thrasher, Northport; and Marty Everse, Brierfield.

By Rhoda Coleman Ellison

A century ago, crime flourished in the central Alabama backwoods. Thieves made their raids from the rough hill country, afterwards retiring safely among protective family and friends. Their primary object was to seize livestock and cotton, but theft sometimes led to violence. The press followed the exploits of these desperadoes avidly and heaped condemnation on those counties that failed to control them. By the early 1890s, Bibb County bore the heaviest burden of shame. It was known as "Bloody Bibb." And yet, from time to time throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Bibb's neighboring counties were bloody, too. Besides producing criminals of their own, they were havens for others who operated without any respect for county lines. This article recounts the exploits of some of these criminals.

Additional Information

- Ayers, Edward L. Vengeance and Justice: Crime and Punishment in the 19th-Century American South (Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Bigelow, Martha Mitchell. "Alabama's Carnival of Crime, 1871-1910," The Alabama Review 3 (April 1950): 123-33.

- Chappell, Gordon T. "'Gentleman Jim': Montgomery's Notorious Robber," The Alabama Review 24 Ganuary 1971): 3-16.

- Ellison, Rhoda Coleman. Bibb County, Alabama: The First Hundred Years, 1818-1918 (University of Alabama Press, 1984).

- Holmes, William F. "Moonshiners and Whitecaps in Alabama, 1893," The Alabama Review 3 (January 1981): 31-49.

- McKinney, Gordon B. "Industrialization and Violence in Appalachia in the 1890's" in An Appalachian Symposium: Essays Written in Honor of Cratis D. Williams, edited by J. W. Williamson (Appalachian State University Press, 1977): 131-44.

About the Author

Rhoda Coleman Ellison, whose article "Little Italy in Rural Alabama" [Alabama Heritage #2, Fall1986] remains one of the most frequently requested articles Alabama Heritage has published, has again tapped the rich resources of her native Bibb County. For this article on nineteenth-century outlaws, Ellison combed the newspapers of the period and interviewed descendants of many of the people involved. Indeed, Ellison's own life touches her article indirectly. In 1892, when her father came as a young man to practice law in Bibb County, he disembarked at the Randolph train station, where Wiley Trott had shot the Louisiana sheriff a year earlier. Ellison believes her father was present at Trott's

trial the day Trott attempted to cut his own throat with a pen knife.

The author would like to thank the following individuals who provided information for the article: John Glasscock, Jemison; Charles Adams, Tuscaloosa; Melvin Thrasher, Northport; and Marty Everse, Brierfield.

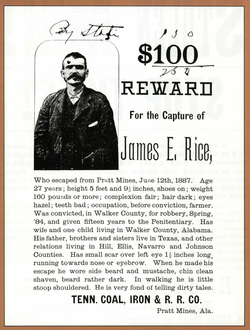

Stop Thief! Nineteenth-Century Wanted Posters

This photographic section features posters selected from the collections of the William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library. Written in the days before photography was common, these posters were created by people who had to rely primarily on their descriptive capabilities in order to distinguish the person or animal or object they sought from others of its kind. Apparently they took to their task with relish, describing teeth, scars, skin color, physical deformities, and personality traits with remarkable candor if not total objectivity.

This photographic section features posters selected from the collections of the William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library. Written in the days before photography was common, these posters were created by people who had to rely primarily on their descriptive capabilities in order to distinguish the person or animal or object they sought from others of its kind. Apparently they took to their task with relish, describing teeth, scars, skin color, physical deformities, and personality traits with remarkable candor if not total objectivity.