|

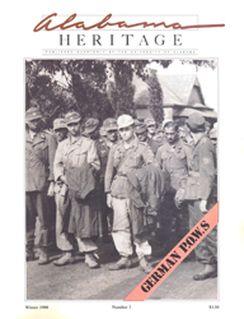

On the cover: Bedraggled members of Rommel's Afrika Korps arrive in Aliceville, Alabama, c. 1943, for detention in a prisoner-of-war camp. (Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History)

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

German prisoners prepare to march from the Aliceville train

German prisoners prepare to march from the Aliceville train depot to the POW camp, c. 1943. (Photo courtesy Alabama Archives)

Inside the Wire: Aliceville and the Afrika Korps

By Randy Wall

For British and Commonwealth forces, the crushing defeat of the Germans at El Alamein, Egypt, in October 1942, was a long-awaited turning point in the war in North Africa. That same victory, however, had exacerbated prisoner-of-war problems for the British. They were already holding over 190,000 Italian prisoners. At El Alamein alone they picked up an additional 30,000 Germans, and new prisoners were being captured daily, among them large numbers of Hitler's Afrika Korps. The space-pressed British needed help, and the US Joint Chiefs of Staff responded to urgent pleas, agreeing to accept prisoners on American soil. Thus was set in motion a series of events that would bring the Afrika Korps to the countryside of Alabama.

Additional Information

About the Author

Randy Wall, a Texas native, spent seven years in Las Vegas where he worked in the convention and entertainment industry. For the past year, he has lived in Tuscaloosa while working on a screenplay. Wall first became interested in World War II POW camps in Alabama after meeting Dr. Stephen Fleck, who, as a physician in the U.S. Army during the war, spent several months in the Aliceville internment facility treating German prisoners. Wall is currently living in Los Angeles, where he is attending the screenwriter's program at the University of Southern California and working on a new screenplay.

The author wishes to thank the people who assisted in the research for this article, particularly Ethelda Potts, Jack Sisty, John Richey, Margie Archibald Colvin, and Sue Ray Stabler, all of Aliceville; Pickens county resident Bobbie Colemanl; and Dr. Stephen Fleck.

By Randy Wall

For British and Commonwealth forces, the crushing defeat of the Germans at El Alamein, Egypt, in October 1942, was a long-awaited turning point in the war in North Africa. That same victory, however, had exacerbated prisoner-of-war problems for the British. They were already holding over 190,000 Italian prisoners. At El Alamein alone they picked up an additional 30,000 Germans, and new prisoners were being captured daily, among them large numbers of Hitler's Afrika Korps. The space-pressed British needed help, and the US Joint Chiefs of Staff responded to urgent pleas, agreeing to accept prisoners on American soil. Thus was set in motion a series of events that would bring the Afrika Korps to the countryside of Alabama.

Additional Information

- Aliceville POW Camp Collection at the Aliceville Public Library, including scrapbooks, illustrations, photographs, and Chip Walker's correspondence with Hans Kopera, March 11, 1983.

- Aliceville POW Camp Collection at the William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama.

- Bailey, Ronald H. Prisoners of War, World War II (Time-Life Books, 1981)

- Collier, Richard. The War in the Desert, World War II (Time-Life Books, 1977)

- Hoole, W. Stanley. "Alabama's World War II Prisoner of War Camps," Alabama Review 20 (April 1967): 83-114.

- Walker, Chip. "German Creative Camp Activities in Camp Aliceville, 1943-1946" Alabama Review 38 (January 1985): 19-37.

About the Author

Randy Wall, a Texas native, spent seven years in Las Vegas where he worked in the convention and entertainment industry. For the past year, he has lived in Tuscaloosa while working on a screenplay. Wall first became interested in World War II POW camps in Alabama after meeting Dr. Stephen Fleck, who, as a physician in the U.S. Army during the war, spent several months in the Aliceville internment facility treating German prisoners. Wall is currently living in Los Angeles, where he is attending the screenwriter's program at the University of Southern California and working on a new screenplay.

The author wishes to thank the people who assisted in the research for this article, particularly Ethelda Potts, Jack Sisty, John Richey, Margie Archibald Colvin, and Sue Ray Stabler, all of Aliceville; Pickens county resident Bobbie Colemanl; and Dr. Stephen Fleck.

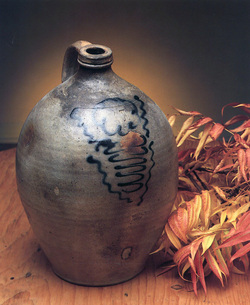

This salt-glazed, one-gallon jug with cobalt

This salt-glazed, one-gallon jug with cobalt decoration was found in Mobile Bay by divers

and was made in the mid-19th

century. (Photo courtesy Chip Cooper;

jug courtesy Mr. and Mrs. J.E. Mulkin)

Traditional Pottery of Mobile Bay

By Joey Brackner

In nineteenth-century Alabama, the potter's work was essential to every settlement. If a family needed a crock, a churn, a chamber pot, or a storage jar, they obtained it from their nearest potter. While traditional potters took pride in their craftsmanship, they wasted little time in decorating their product. What mattered to the average nineteenth-century Alabamian was the item's utilitarian value. Thus, folk pottery reveals much about the workings of everyday life in the community in which it was made. This article examines the pottery of Mobile Bay, asking what these crocks, churns, and jars can tell us about their area of origin.

Additional Information

About the Author

Joey Brackner, a native of Fairfield, Alabama, directs the Folklife Program of the Alabama State Council on the Arts. He holds an undergraduate degree from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a master's degree in anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin. Currently, Brackner is preparing a manuscript on Greenwood Cemetery, Tuscaloosa, and he is co-directing a thirty-minute color film n folk potter Jerry Brown of Hamilton, Alabama. He is also coordinating the Mobile Glazed Earthenware Project, a joint effort between the Mobile Historic Development Commission and the University of South Alabama. With funding from the Smith foundation of Daphne, Alabama, project participants--primarily Dr. Wayne Isphording of the University of South Alabama Geoogy Department--have begun analyzing the contents of Mobile Bay pottery shards in an effort to learn more about the indigenous potters who have worked there in the European tradition.

By Joey Brackner

In nineteenth-century Alabama, the potter's work was essential to every settlement. If a family needed a crock, a churn, a chamber pot, or a storage jar, they obtained it from their nearest potter. While traditional potters took pride in their craftsmanship, they wasted little time in decorating their product. What mattered to the average nineteenth-century Alabamian was the item's utilitarian value. Thus, folk pottery reveals much about the workings of everyday life in the community in which it was made. This article examines the pottery of Mobile Bay, asking what these crocks, churns, and jars can tell us about their area of origin.

Additional Information

- Brackner, Joey, and Ron Countryman. Pottery from the Mountains of Alabama (Bessemer Hall of History, 1986).

- Burrison, John. Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Potters (University of Georgia Press, 1983).

- Greer, Georgeanna H. American Stoneware (Schiffer Publishing Ltd. 1981).

- Sweezy, Nancy. Raised in Clay (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984).

- Willett, Henry E. and Joey Brackner. The Traditional Pottery of Alabama (Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1983).

- Zug, Charles G. Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

About the Author

Joey Brackner, a native of Fairfield, Alabama, directs the Folklife Program of the Alabama State Council on the Arts. He holds an undergraduate degree from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a master's degree in anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin. Currently, Brackner is preparing a manuscript on Greenwood Cemetery, Tuscaloosa, and he is co-directing a thirty-minute color film n folk potter Jerry Brown of Hamilton, Alabama. He is also coordinating the Mobile Glazed Earthenware Project, a joint effort between the Mobile Historic Development Commission and the University of South Alabama. With funding from the Smith foundation of Daphne, Alabama, project participants--primarily Dr. Wayne Isphording of the University of South Alabama Geoogy Department--have begun analyzing the contents of Mobile Bay pottery shards in an effort to learn more about the indigenous potters who have worked there in the European tradition.

Lella Warren, c. 1915. (Courtesy Lella

Lella Warren, c. 1915. (Courtesy LellaWarren manuscript collection, Auburn

University at Montgomery)

Lella Warren: Alabama's Margaret Mitchell?

By Nancy G. Anderson

In the mid-1930s, readers for Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., advised the publisher to obtain the rights to Foundation Stone, a novel by Lella Warren. This book, they predicted, would be "an American epic" and a great commercial success. They were right. Foundation Stone, the saga of the pioneering Whetstone family who settled in Alabama in the 1820s, took the country by storm when it appeared in September 1940. Within weeks of its publication, the novel moved quickly up the nation's best-seller lists where it remained throughout 1940 and 1941, at times selling at the rate of one thousand copies a day. The book was a success, and its author--forty-one-year-old Lella Warren--was a national celebrity. This period would be the pinnacle of Warren's career, and though both she and her novel were destined to slip into obscurity, their story is one that is tied closely to the story of Alabama itself.

Additional Information

About the Author

Nancy Anderson, Director of Composition at Auburn University at Montgomery, first heard Lella Warren's name in the summer of 1976 when a friend at Princeton University Press recommended Foundation Stone. Anderson read the book, liked it, and was pleased to learn that the Alabama ETV program Alabama Perspectives had recently recorded Lella Warren reading passages from her books. From the television station, Anderson obtained Warren's address and began a correspondence that led to a visit with the author in her Washington apartment, a few months before Warren's death in 1982. Later, Warren's daughter, Lee Spanogle Shipman, turned over her mother's manuscripts, letters, research notes, and family photographs to Anderson for inventory and cataloging. As a result of Anderson's ongoing efforts to acquaint Alabamians with the work of Lella Warren, Foundation Stone was recently reprinted in paperback by the University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, as part of the Alabama Classics Series.

By Nancy G. Anderson

In the mid-1930s, readers for Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., advised the publisher to obtain the rights to Foundation Stone, a novel by Lella Warren. This book, they predicted, would be "an American epic" and a great commercial success. They were right. Foundation Stone, the saga of the pioneering Whetstone family who settled in Alabama in the 1820s, took the country by storm when it appeared in September 1940. Within weeks of its publication, the novel moved quickly up the nation's best-seller lists where it remained throughout 1940 and 1941, at times selling at the rate of one thousand copies a day. The book was a success, and its author--forty-one-year-old Lella Warren--was a national celebrity. This period would be the pinnacle of Warren's career, and though both she and her novel were destined to slip into obscurity, their story is one that is tied closely to the story of Alabama itself.

Additional Information

- Anderson, Nancy G. "Lella Warren," Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook: 1983 (Gale, 1984): 330-335.

- _____. "Lella Warren's Literary Gift--Alabama," Clearing the Thicket (Mercer University Press, 1985): 77-88.

- Warren, Lella. Foundation Stone (Knopf, 1940; Collins, 1941; reprint by the University of Alabama Press, 1986).

- _____. A Touch of Earth (Simon & Schuster, 1926).

- _____. Whetstone Walls (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1952).

About the Author

Nancy Anderson, Director of Composition at Auburn University at Montgomery, first heard Lella Warren's name in the summer of 1976 when a friend at Princeton University Press recommended Foundation Stone. Anderson read the book, liked it, and was pleased to learn that the Alabama ETV program Alabama Perspectives had recently recorded Lella Warren reading passages from her books. From the television station, Anderson obtained Warren's address and began a correspondence that led to a visit with the author in her Washington apartment, a few months before Warren's death in 1982. Later, Warren's daughter, Lee Spanogle Shipman, turned over her mother's manuscripts, letters, research notes, and family photographs to Anderson for inventory and cataloging. As a result of Anderson's ongoing efforts to acquaint Alabamians with the work of Lella Warren, Foundation Stone was recently reprinted in paperback by the University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, as part of the Alabama Classics Series.