|

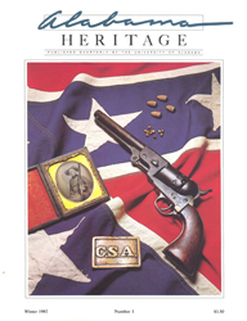

On the cover: Ambrotype image of William J. Rozelle, Company A, Nineteenth Alabama Infantry, C.S.A., holding his Mississippi rifle, c. 1861; Rigdon, Ansley revolver, a Confederate copy of Samuel Colt's popular .36 caliber Navy-model pistol; bullets and percussion caps; Confederate belt buckle. (Photo by Chip Cooper; ambrotype courtesy Hodo Strickland)

Although this issue is no longer in print, scroll down to find some features from this issue that are available for purchase as downloadable PDFs.

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

Civil War small arms. (Photo

courtesy Chip Cooper)

Civil War small arms. (Photo

courtesy Chip Cooper)

Arms for Dixie

By Douglas E. Jones

At the beginning of the Civil War, the North produced 97 percent of all firearms and railroad equipment in America, while the South had not a single battery of field artillery and only one factory capable of fabricating a military weapon of any kind. During the course of the four-year war, however, the South managed to create from scratch an amazingly effective ordnance system producing everything form uniforms to powder to cannon. The heart of that ordnance system lay in the state of Alabama. Together, the Selma operation and the state's own small manufacturing firms succeeded in creating, however briefly, Alabama's first industrial revolution.

By Douglas E. Jones

At the beginning of the Civil War, the North produced 97 percent of all firearms and railroad equipment in America, while the South had not a single battery of field artillery and only one factory capable of fabricating a military weapon of any kind. During the course of the four-year war, however, the South managed to create from scratch an amazingly effective ordnance system producing everything form uniforms to powder to cannon. The heart of that ordnance system lay in the state of Alabama. Together, the Selma operation and the state's own small manufacturing firms succeeded in creating, however briefly, Alabama's first industrial revolution.

Additional Information

About the Author

Doug Jones, professor of geology at the University of Alabama, director of the Alabama State Museum of Natural History, and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences from 1969 to 1984, became interested in the Civil War as a teenager, when, he says, "there were still things around on battlefields to pick up." In the intervening years, Jones has become an avid collector of Civil War memorabilia, an accomplished restorer of antique weapons, and in 1980, a member of the American Society of Arms Collectors. "So much of early American society," he says, "is reflected in the history of utility items like weapons.'' Weapons terminology has even become part of our language, says Jones, citing phrases like "lock, stock, and barrel,'' ''flash in the pan,'' and ''going off half-cocked," and the onomatopoeia "sis-boom-bah" (the sound of a cannon salute: "sis," the hiss of the fuse, ''boom,'' the report of the gun, and ''bah,'' the echo of

the shot).

The author wishes to thank Hodo Strickland and Jerry Oldshue for their assistance with portions of this article.

- Albaugh, William A., III, and Edward N. Simmons. Confederate Arms, (Stackpole, 1957).

- Armes, Ethel. The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama (The Chamber of Commerce, 1910).

- Edwards, William B. Civil War Guns (Stackpole, 1962).

- Jones, James Pickett. Yankee Blitzkrieg: Wilson 's Raid through Alabama and Georgia (University of Georgia Press, 1976).

- Ripley, Warren. Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War (Promontory Press, 1970).

- Stephen, Walter W. "The Brooke Guns from Selma," Alabama Historical Quarterly 20 (Fall 1958): 462-75.

- Tepper, Sol H. "Torpedoes? Damn!": Ordeal at Selma Gun Foundry and Battle of Mobile Bay (privately printed, 1979).

- Thomas, Emory M. The Confederate Nation: 1861-1865 (Harper & Row, 1979).

- Vandiver, Frank E. Ploughshares into Swords: Josiah Gorgas and Confederate Ordnance (University of Texas Press, 1952).

About the Author

Doug Jones, professor of geology at the University of Alabama, director of the Alabama State Museum of Natural History, and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences from 1969 to 1984, became interested in the Civil War as a teenager, when, he says, "there were still things around on battlefields to pick up." In the intervening years, Jones has become an avid collector of Civil War memorabilia, an accomplished restorer of antique weapons, and in 1980, a member of the American Society of Arms Collectors. "So much of early American society," he says, "is reflected in the history of utility items like weapons.'' Weapons terminology has even become part of our language, says Jones, citing phrases like "lock, stock, and barrel,'' ''flash in the pan,'' and ''going off half-cocked," and the onomatopoeia "sis-boom-bah" (the sound of a cannon salute: "sis," the hiss of the fuse, ''boom,'' the report of the gun, and ''bah,'' the echo of

the shot).

The author wishes to thank Hodo Strickland and Jerry Oldshue for their assistance with portions of this article.

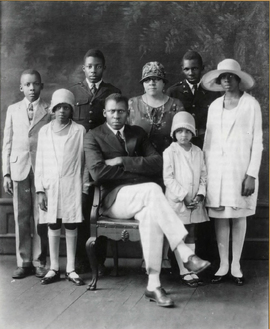

Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Monroe Campbell and family,

Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Monroe Campbell and family,1932. (Photo courtesy P.H. Polk estate.)

P.H. Polk

By Maryanne G. Culpepper

For over fifty years, beginning in the 1930s, Prentice Herman Polk's skillful hand and artistic sensibility documented the rural South through photography. These were wrenching years of transition for both the region and its people. By the time Polk was born at the end of the nineteenth century, the first generation of free black men and women had grown to adulthood and had found themselves rootless in a new economic, social, and political order. As the twentieth century dawned, the outlook for African Americans was bleak, but a new sense of racial pride was taking shape. Freed from the restrictions of slavery, black men and women, for the first time, were able to pursue careers in the arts, searching for new ways to express the black experience in America. One of those black artists was the photography P.H. Polk.

By Maryanne G. Culpepper

For over fifty years, beginning in the 1930s, Prentice Herman Polk's skillful hand and artistic sensibility documented the rural South through photography. These were wrenching years of transition for both the region and its people. By the time Polk was born at the end of the nineteenth century, the first generation of free black men and women had grown to adulthood and had found themselves rootless in a new economic, social, and political order. As the twentieth century dawned, the outlook for African Americans was bleak, but a new sense of racial pride was taking shape. Freed from the restrictions of slavery, black men and women, for the first time, were able to pursue careers in the arts, searching for new ways to express the black experience in America. One of those black artists was the photography P.H. Polk.

Additional Information

About the Author

Maryanne Gillis Culpepper, a producer/director for Auburn Television, Auburn University, holds a master's degree in journalism and communications from the University of Florida. With Bruce Kuerten, she co-produced "Lost in Time," a one-hour documentary on southeastern prehistory that aired nationally on PBS in 1985, and "First Frontier," a dramatic documentary on southeastern history (1540-1835), slated for broadcast in February 1987. Currently she is working on "Living Blues,'' a program on the history of blues and its impact on popular music.

Culpepper first met P. H. Polk in 1981, when she was researching a multimedia presentation for Tuskegee Institute on the life of George Washington Carver. Her interviews with Polk form the basis for this article.

For his assistance in assembling photographs for this article, the editors would like to thank Mr. Donald Polk.

- Black Photographers Annual, Inc. The Black Photographers Annual, Vol. 2 (Brooklyn: Black Photographers Annual, Inc., 1974).

- Coar, Valencia Hollins, ed. A Century of Black Photographers, 1840-1960 (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1983).

- Haskins, James. James Van DerZee: The Picture-Takin' Man (Dodd, Mead & Co., 1979).

- Higgins, Chester, Jr., and Orde Coombs. Some Time Ago: A Historical Portrait of Black Americans from 1850-1950 (Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1980).

- Parks, Gordon. To Smile in Autumn: A Memoir (W. W. Norton, 1979).

- Willis-Thomas, Deborah. Black Photographers, 1840-1940: An Illustrated Bio-Bibliography (Garland Publishing, 1985).

About the Author

Maryanne Gillis Culpepper, a producer/director for Auburn Television, Auburn University, holds a master's degree in journalism and communications from the University of Florida. With Bruce Kuerten, she co-produced "Lost in Time," a one-hour documentary on southeastern prehistory that aired nationally on PBS in 1985, and "First Frontier," a dramatic documentary on southeastern history (1540-1835), slated for broadcast in February 1987. Currently she is working on "Living Blues,'' a program on the history of blues and its impact on popular music.

Culpepper first met P. H. Polk in 1981, when she was researching a multimedia presentation for Tuskegee Institute on the life of George Washington Carver. Her interviews with Polk form the basis for this article.

For his assistance in assembling photographs for this article, the editors would like to thank Mr. Donald Polk.

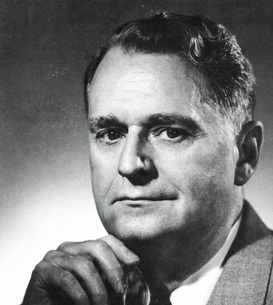

Writer William March (Courtesy

Writer William March (CourtesyW.S. Hoole Special Collections

Library, University of Alabama)

Alabama's William March

By Roy S. Simmonds

Roy S. Simmonds recounts the life of Alabama's forgotten genius, William March. March's evocation of Alabama small-town life at the turn of the century is vivid and unrelenting in its veracity. Whatever the verdict of posterity may be, there is no denying that March's legacy to the world will remain a rich and revealing chapter in the literary history of Alabama.

Additional Information

About the Author

Roy Simmonds, a retired British government official, was born in London, England, and now lives in Billericay, Essex. Since his teenage years, Simmonds has had "an abiding interest in modern American literature." Over the course of the past twenty years, he has contributed articles on John Steinbeck and William March to various scholarly journals in the United States. He became interested in William March sixteen years ago, and from the moment of his first acquaintance with the Alabama author's work, Simmonds writes, he ''became convinced that March was one of the most shamefully neglected of all twentieth-century American writers."

Simmonds' biography of March, The Two Worlds of William March, was published in 1984 by The University of Alabama Press. At present, he is writing a biography of the American short story anthologist Edward J. O'Brien, who edited the annual Best Short Stories collections from 1915 until his death in 1941. These short story anthologies, says Simmonds, led to his interest in modem American literature.

By Roy S. Simmonds

Roy S. Simmonds recounts the life of Alabama's forgotten genius, William March. March's evocation of Alabama small-town life at the turn of the century is vivid and unrelenting in its veracity. Whatever the verdict of posterity may be, there is no denying that March's legacy to the world will remain a rich and revealing chapter in the literary history of Alabama.

Additional Information

- Bolton, Clint. "In Memoriam Bill March," Vieux Carre Courier, August 16, 1968.

- Crowder, Richard. ''The Novels of William March,'' University of Kansas City Review 15 (Winter 1948): 111-29.

- Emerson, O.B. "William March and Southern Literature," Carson-Newman College Faculty Studies 1 (1968): 3-10.

- Going, William T. Essays on Alabama Literature (University of Alabama Press, 1975).

- _____. "William March: Regional Perspective and Beyond," Papers on Language and Literature 13 (Fall 1977): 430-43.

- Simmonds, Roy S. The Two Worlds of William March (University of Alabama Press, 1984).

- _____. William March: An Annotated Checklist (University of Alabama Press, 1988).

- Tallant, Robert. "Poor Pilgrim, Poor Stranger," Saturday Review 37 (July 17, 1954) 9: 33-34.

About the Author

Roy Simmonds, a retired British government official, was born in London, England, and now lives in Billericay, Essex. Since his teenage years, Simmonds has had "an abiding interest in modern American literature." Over the course of the past twenty years, he has contributed articles on John Steinbeck and William March to various scholarly journals in the United States. He became interested in William March sixteen years ago, and from the moment of his first acquaintance with the Alabama author's work, Simmonds writes, he ''became convinced that March was one of the most shamefully neglected of all twentieth-century American writers."

Simmonds' biography of March, The Two Worlds of William March, was published in 1984 by The University of Alabama Press. At present, he is writing a biography of the American short story anthologist Edward J. O'Brien, who edited the annual Best Short Stories collections from 1915 until his death in 1941. These short story anthologies, says Simmonds, led to his interest in modem American literature.