|

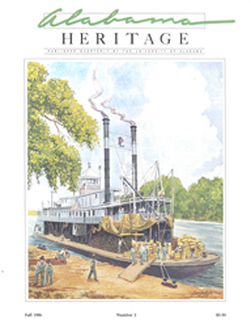

On the cover: The City of Mobile, a stern-wheeler built in Mobile in 1898 and destroyed in that city by the 1916 hurricane, at a landing on the Alabama River. (Illustration by Terry Henderson; original photograph courtesy James K. McNutt)

Although this issue is no longer in print, scroll down to find some features from this issue that are available for purchase as downloadable PDFs.

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

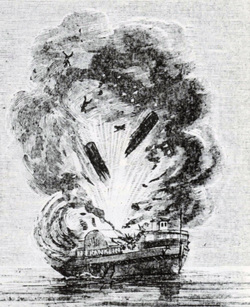

Near Mobile in 1836, a boiler exploded

Near Mobile in 1836, a boiler exploded aboard the steamer Ben Franklin,

depicted here. (Courtesy W.S. Hoole Special

Collections Library, University of Alabama)

Steamboat Travel in Early Alabama

By Robert O. Mellown

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of steamboats to the development of Alabama, culturally, socially, or economically. The state entered the Union in 1819, at the beginning of the steam era and the period of rapid growth in river transportation in America. Steamboats provided a fast and efficient transportation system, helping the state to build its towns, to move its people, and to transport its crops. The steamboat boom would continue until the Civil War, at which time a fractured infrastructure and an expanding railroad industry finally ended the reign of the Alabama steamboats.

Additional Information

About the Author

Robert Mellown, a Sumter County native, received his doctorate in art history from the University of North Carolina, where he specialized in the study of nineteenth-century American painting and sculpture. A member of the art history faculty at the University of Alabama since 1971, Mellown has focused his research on antebellum architecture in the Tuscaloosa area and, more recently, on antebellum Alabama steamboats. For the past two years he has been constructing a model stern-wheeler in his spare time. "Progress has been slow," he says. "I keep gluing my fingers together."

By Robert O. Mellown

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of steamboats to the development of Alabama, culturally, socially, or economically. The state entered the Union in 1819, at the beginning of the steam era and the period of rapid growth in river transportation in America. Steamboats provided a fast and efficient transportation system, helping the state to build its towns, to move its people, and to transport its crops. The steamboat boom would continue until the Civil War, at which time a fractured infrastructure and an expanding railroad industry finally ended the reign of the Alabama steamboats.

Additional Information

- For firsthand accounts of steamboat travel in Alabama prior to the Civil War, see references listed on page 11.

- "Landing Cotton on the Alabama River," Ballou 's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion 8 (April 21, 1855): 252.

- Frazer, Mell A. "Early History of Steamboats in Alabama," Alabama Polytechnic Institute Historical Studies, Ser. 3, # 1 (API, 1907) ..

- Foster, James Fleetwood. Ante-Bellum Floating Palaces of the Alabama River, and the "Good Old Times in Dixie" (Wilcox Banner, 1940; reprint ed. by Bert Neville, Selma: 1967).

- Lloyd, James T. Lloyd's Steamboat Directory and Disasters on the Western Waters, ... (James T. Lloyd, 1856).

- Neville, Bert. Directory of River Packets in the Mobile-Alabama-Warrior-Tombigbee Trades, 1818-1932 (Alabama: 1962).

- Watson, Ken. Paddle Steamers: An Illustrated History of Steamboats on the Mississippi and Its Tributaries (W. W. Norton, 1985).

About the Author

Robert Mellown, a Sumter County native, received his doctorate in art history from the University of North Carolina, where he specialized in the study of nineteenth-century American painting and sculpture. A member of the art history faculty at the University of Alabama since 1971, Mellown has focused his research on antebellum architecture in the Tuscaloosa area and, more recently, on antebellum Alabama steamboats. For the past two years he has been constructing a model stern-wheeler in his spare time. "Progress has been slow," he says. "I keep gluing my fingers together."

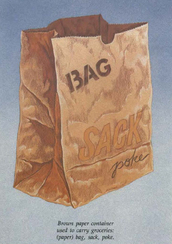

Brown paper container

Brown paper containerused to carry groceries:

(paper) bag; sack, poke.

(Illustration by Terry Henderson)

Is Southern English Disappearing?

By Ann H. Pitts

It is possible for a language, like a species of animal, to become extinct in a generation, but this seldom happens without the destruction of the people who speak that language. It is, therefore, surprising to discover that many people believe that southern US dialects are in decline--particularly while there are still millions of native speakers. Those predicting the decline of southern English base their arguments on seemingly common-sense observations: the decline of agrarian culture and the rise of mass media both seem to forecast the elimination of southern US dialects as the South slowly becomes absorbed into the broader US culture. But do such predictions accurately reflect the future of southern English? In this article, Ann H. Pitts argues that they do not.

By Ann H. Pitts

It is possible for a language, like a species of animal, to become extinct in a generation, but this seldom happens without the destruction of the people who speak that language. It is, therefore, surprising to discover that many people believe that southern US dialects are in decline--particularly while there are still millions of native speakers. Those predicting the decline of southern English base their arguments on seemingly common-sense observations: the decline of agrarian culture and the rise of mass media both seem to forecast the elimination of southern US dialects as the South slowly becomes absorbed into the broader US culture. But do such predictions accurately reflect the future of southern English? In this article, Ann H. Pitts argues that they do not.

Additional Information

- Cassidy, Frederic G. Dictionary of American Regional English, Vol. I: Introduction and A-C (Harvard University Press, 1985).

- Dengler, Carl L. Place Over Time: The Continuity of Southern Distinctiveness (Louisiana State University Press, 1977).

- McDavid, Raven I. "The Urbanization of American English," in Varieties of American English: Essays by Raven I. McDavid, Jr., ed. Anwar S. Dil (Stanford University Press, 1980), pp. 114-30.

- Miller, Mary R. "The Language of Power and Solidarity," The SECOL Review 9 (1985) 2: 114-42.

- Pitts, Ann H. "Flip-Flop Prestige in American tune, duke, news," American Speech 61 (Summer 1986) 2:130-38.

- Ryan, Ellen Bouchard "Why Do Low-Prestige Language Varieties Persist?" in Language and Social Psychology, ed. Howard Giles and Robert N. St. Clair (B. Blackwell, 1979).

About the Author

Ann Pitts grew up in Birmingham, took a B.A. in English at Birmingham-Southern College and an M.A. and Ph.D. in English language and linguistics at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor). Since 1982 she has been an assistant professor of English at Auburn University, responsible for the department's classes in general linguistics, phonology, grammar, and language variation. In Michigan, while studying the phonology of American English, Pitts (who has a Southern accent herself) became aware of the social pressures against Southern-accented speech. Since then, she says, she has sought to educate people about the history of Southern American English, its inherent interest, and its right to exist--a message "implicit or explicit" in all her linguistics classes at Auburn.

Rickwood Field, constructed in Birmingham in 1910, was home

Rickwood Field, constructed in Birmingham in 1910, was home field for the Black Barons, who rented the stadium from its

white owners on dates with then minor league white Barons

were not in town. (Courtesy the Birmingham Barons)

Slidin' and Ridin': At Home and on the Road with the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons

By Tim Cary

Birmingham has always been a baseball town, and as far back as the late nineteenth century, white professional baseball was popular in the city. Prevented from competing against whites, African Americans organized their own teams across Alabama. The Birmingham Black Barons was one of these teams. Formed in the 1920s, the Black Barons played until the early 1960s. In 1948 they made a play to win the Negro World Series; this is the story of their struggle. Most of the players never achieved the fame of other players from other teams, men such as Jackie Robinson. But for more than forty years the Birmingham Black Barons were an institution and an inspiration to the city's black community.

Additional Information

About the Author

Tim Cary, assistant special collections librarian at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, has master's degrees in American history and library science, both from the University of Iowa. A native of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and a lifelong baseball fan, Cary grew up rooting for the Milwaukee Braves and later the Milwaukee Brewers. This study of the Birmingham Black Barons, conducted while the author was assistant curator at the William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama, has allowed him to combine his interests in American social history and the history of baseball.

The author would like to thank former Black Barons Lorenzo "Piper" Davis, Johnnie Cowan, Harvey "Pete" Peterson, the Reverend Nathaniel Pollard, and William Powell, all of whom were interviewed for this article.

By Tim Cary

Birmingham has always been a baseball town, and as far back as the late nineteenth century, white professional baseball was popular in the city. Prevented from competing against whites, African Americans organized their own teams across Alabama. The Birmingham Black Barons was one of these teams. Formed in the 1920s, the Black Barons played until the early 1960s. In 1948 they made a play to win the Negro World Series; this is the story of their struggle. Most of the players never achieved the fame of other players from other teams, men such as Jackie Robinson. But for more than forty years the Birmingham Black Barons were an institution and an inspiration to the city's black community.

Additional Information

- Atkins, Leah Rawls. The Valley and the Hills: An Illustrated History of Birmingham and Jefferson County (Windsor Press, 1981).

- Bruce, Janet. The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (University Press of Kansas, 1985).

- Holway, John. Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (Dodd, Mead & Co., 1975).

- Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White (Prentice-Hall, 1970).

- Rogosin, Donn. Invisible Men: Life in Baseball's Negro Leagues (Atheneum, 1983).

- Rosengarten, Theodore. "Reading the Hops: Recollections of Lorenzo Piper Davis and the Negro Baseball League," Southern Exposure 5 (1977): 62-79.

About the Author

Tim Cary, assistant special collections librarian at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, has master's degrees in American history and library science, both from the University of Iowa. A native of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and a lifelong baseball fan, Cary grew up rooting for the Milwaukee Braves and later the Milwaukee Brewers. This study of the Birmingham Black Barons, conducted while the author was assistant curator at the William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama, has allowed him to combine his interests in American social history and the history of baseball.

The author would like to thank former Black Barons Lorenzo "Piper" Davis, Johnnie Cowan, Harvey "Pete" Peterson, the Reverend Nathaniel Pollard, and William Powell, all of whom were interviewed for this article.

Little Italy in Rural Alabama

By Rhoda Coleman Ellison

In the mid-1880s, the first immigrants arrived in Blocton, Alabama. Some were Slavic, others Polish, but the majority were Italians. Many came from villages in the hills above Bologna, south of Florence, and from the Italian colony on the island of Corsica. Employed as shepherds, farmers, or gardeners in their native land, they had been lured to Alabama by coal-mining company recruiters looking for cheap labor, and later, by letters from relatives and friends who had preceded them to the Bibb County hills. Unable to speak English, these immigrants met with problems communicating. Largely Roman Catholic, they faced religious intolerance from their Protestant neighbors. Strangers in a strange land, they set up their own community in Blocton. It was known as Little Italy.

Additional Information

Sources for this article include Bibb County newspapers of the period, the biennial reports of the Alabama State Inspector of Mines, 1892-94, the Bibb County Circuit Court Indictment Record, Vol. 5, and the following individuals, whom the author wishes to thank · for providing valuable information through interviews:

In Tuscaloosa-Charles E. Adams, whose knowledge of the area made possible the Little Italy map, and Dr. Gerald Globetti; in Birmingham-Rose Ferrire Rossi, Leno Rossi, Angel Biagi Ferrire, Bruno Globetti, the late William R. Young, Jr.; in West Blocton-the late Marie Nuggi Cinelli, Lemuel Parker, the late Richard Moore; in Centreville-the late Joseph Province (Providenza); in Atlanta-Jack Lawrence.

About the Author

Rhoda Coleman Ellison, a Bibb County native, has personal as well as professional interest in the rural Alabama region that once housed Little Italy. Not only is she a descendant of one of the county's first settlers, but her father, an attorney who practiced law in Bibb County from 1892 to 1947, included among his clients Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company--the company that imported the Italians to Bibb County to work the mines. Ellison, who holds degrees from Randolph-Macon, Columbia University, and the University of North Carolina (where she received a doctorate in English), was an English professor at Huntingdon College for forty-one years and served as chairman of the department from 1959 to 1971. She has published numerous articles in the Alabama Historical Quarterly and the Alabama Review and is the author of five books on Alabama history, all published by the University of Alabama Press. Her most recent book, Bibb County, Alabama: The First Hundred Years, 1818-1918 (UA Press, 1984), won the Alabama Historical Association's Sulzby Award for the best book on Alabama history published that year.

By Rhoda Coleman Ellison

In the mid-1880s, the first immigrants arrived in Blocton, Alabama. Some were Slavic, others Polish, but the majority were Italians. Many came from villages in the hills above Bologna, south of Florence, and from the Italian colony on the island of Corsica. Employed as shepherds, farmers, or gardeners in their native land, they had been lured to Alabama by coal-mining company recruiters looking for cheap labor, and later, by letters from relatives and friends who had preceded them to the Bibb County hills. Unable to speak English, these immigrants met with problems communicating. Largely Roman Catholic, they faced religious intolerance from their Protestant neighbors. Strangers in a strange land, they set up their own community in Blocton. It was known as Little Italy.

Additional Information

Sources for this article include Bibb County newspapers of the period, the biennial reports of the Alabama State Inspector of Mines, 1892-94, the Bibb County Circuit Court Indictment Record, Vol. 5, and the following individuals, whom the author wishes to thank · for providing valuable information through interviews:

In Tuscaloosa-Charles E. Adams, whose knowledge of the area made possible the Little Italy map, and Dr. Gerald Globetti; in Birmingham-Rose Ferrire Rossi, Leno Rossi, Angel Biagi Ferrire, Bruno Globetti, the late William R. Young, Jr.; in West Blocton-the late Marie Nuggi Cinelli, Lemuel Parker, the late Richard Moore; in Centreville-the late Joseph Province (Providenza); in Atlanta-Jack Lawrence.

About the Author

Rhoda Coleman Ellison, a Bibb County native, has personal as well as professional interest in the rural Alabama region that once housed Little Italy. Not only is she a descendant of one of the county's first settlers, but her father, an attorney who practiced law in Bibb County from 1892 to 1947, included among his clients Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company--the company that imported the Italians to Bibb County to work the mines. Ellison, who holds degrees from Randolph-Macon, Columbia University, and the University of North Carolina (where she received a doctorate in English), was an English professor at Huntingdon College for forty-one years and served as chairman of the department from 1959 to 1971. She has published numerous articles in the Alabama Historical Quarterly and the Alabama Review and is the author of five books on Alabama history, all published by the University of Alabama Press. Her most recent book, Bibb County, Alabama: The First Hundred Years, 1818-1918 (UA Press, 1984), won the Alabama Historical Association's Sulzby Award for the best book on Alabama history published that year.