|

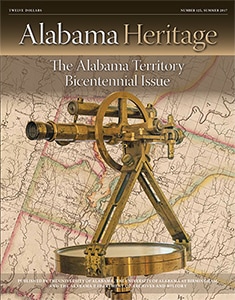

On the cover: Foreground: Nineteenth-century surveyor’s theodolite on display in a re-creation of the Federal Land Office at Constitution Village in Huntsville. (Robin McDonald) Background: Detail of the 1819 update of John Melish’s map of the Alabama Territory. (Library of Congress)

|

EDITOR'S NOTE: We are honored to have the support of the Alabama Bicentennial Commission (ABC) for this special issue of Alabama Heritage. Please see Alabama200.org for more information about the ABC and upcoming bicentennial-related events.

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

A LONG ROAD TO BECOMING A TERRITORY

by Edwin C. Bridges

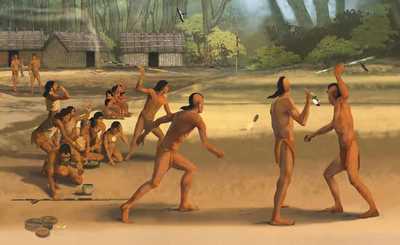

Before Alabama became a territory, it had a rich human presence, dating back to before 11,000 BCE. Native Americans in the land that would become known as Alabama inhabited a landscape with mammoths, mastodons, sloths, and bison. For the Mississippian Indians, the area was an epicenter of economic and commercial growth. The arrival of European explorers in the sixteenth century reshaped communities by introducing diseases that ravaged native populations. Over the following centuries, Native Americans and Europeans negotiated—sometimes violently—over the land that would eventually become a territory of the United States.

About the Author

Edwin C. Bridges grew up in the Wiregrass part of Southwest Georgia. He attended Furman University and received his MA and PhD degrees from the University of Chicago. He was appointed director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History in 1982 and served there for just over thirty years. He continues to be active in Alabama history, working with the Alabama Bicentennial Commission and several other state history organizations. He is the author of Alabama: The Making of an American State, published last fall by the University of Alabama Press.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Alabama: The Making of an American State by Edwin C. Bridges http://www.uapress.ua.edu/product/Alabama,6460.aspx

Timeline of 1492—1700: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1519.html

Timeline of 1701—1800: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1702.html

The Territorial Period and Early Statehood http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1548

Hernando De Soto: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/brnzdrs/1.html

Muscogee (Creek) Nation: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-108

by Edwin C. Bridges

Before Alabama became a territory, it had a rich human presence, dating back to before 11,000 BCE. Native Americans in the land that would become known as Alabama inhabited a landscape with mammoths, mastodons, sloths, and bison. For the Mississippian Indians, the area was an epicenter of economic and commercial growth. The arrival of European explorers in the sixteenth century reshaped communities by introducing diseases that ravaged native populations. Over the following centuries, Native Americans and Europeans negotiated—sometimes violently—over the land that would eventually become a territory of the United States.

About the Author

Edwin C. Bridges grew up in the Wiregrass part of Southwest Georgia. He attended Furman University and received his MA and PhD degrees from the University of Chicago. He was appointed director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History in 1982 and served there for just over thirty years. He continues to be active in Alabama history, working with the Alabama Bicentennial Commission and several other state history organizations. He is the author of Alabama: The Making of an American State, published last fall by the University of Alabama Press.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Alabama: The Making of an American State by Edwin C. Bridges http://www.uapress.ua.edu/product/Alabama,6460.aspx

Timeline of 1492—1700: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1519.html

Timeline of 1701—1800: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1702.html

The Territorial Period and Early Statehood http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1548

Hernando De Soto: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/brnzdrs/1.html

Muscogee (Creek) Nation: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-108

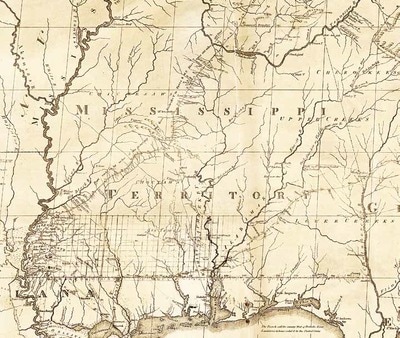

This Francis Shallus map, “The State of Mississippi and Alabama

Territory,” inaccurately shows the Alabama-Mississippi border as a straight line. The location of the border was the subject

of intense disagreement between the eastern and western groups of settlers before statehood. (Library of Congress)

This Francis Shallus map, “The State of Mississippi and Alabama

Territory,” inaccurately shows the Alabama-Mississippi border as a straight line. The location of the border was the subject

of intense disagreement between the eastern and western groups of settlers before statehood. (Library of Congress)

“MORE OR LESS ARBITRARY”:

THE LOCATION OF THE ALABAMA-MISSISSIPPI

BORDER

by Mike Bunn

Today, state and territorial borders may seem sacrosanct, things that could never have been in question. However, prior to the creation of the Alabama Territory, numerous competing interests vied to claim land for themselves, and the territory’s borders were anything but certain. Historian Mike Bunn explores the many considerations—from territorial sectionalism to a desire to subvert the lethargic pace of government policy—that helped shape the Alabama Territory.

About the Author

Mike Bunn is a public historian who has worked with a variety of cultural heritage institutions in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia during his career. He currently serves as director of operations at Historic Blakeley State Park in Spanish Fort, Alabama. He is active with several state and national historical organizations and is a member of the board of directors of the Alabama Historical Association. He also serves as editor of Muscogiana, a local history journal published by the Muscogee County (Georgia) Genealogical Society. Bunn is the author of several books and numerous articles on the colonial-era, antebellum, and Civil War South, which give particular attention to its numerous historic sites. Material for this article was taken from his forthcoming history and guide to Alabama’s territorial and early statehood years, to be published by the University of Alabama Press. Bunn lives in Daphne, Alabama, with his wife, Tonya, and daughter, Zoey.

Additional Information

For more on Alabama’s boundaries, see http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-160

THE LOCATION OF THE ALABAMA-MISSISSIPPI

BORDER

by Mike Bunn

Today, state and territorial borders may seem sacrosanct, things that could never have been in question. However, prior to the creation of the Alabama Territory, numerous competing interests vied to claim land for themselves, and the territory’s borders were anything but certain. Historian Mike Bunn explores the many considerations—from territorial sectionalism to a desire to subvert the lethargic pace of government policy—that helped shape the Alabama Territory.

About the Author

Mike Bunn is a public historian who has worked with a variety of cultural heritage institutions in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia during his career. He currently serves as director of operations at Historic Blakeley State Park in Spanish Fort, Alabama. He is active with several state and national historical organizations and is a member of the board of directors of the Alabama Historical Association. He also serves as editor of Muscogiana, a local history journal published by the Muscogee County (Georgia) Genealogical Society. Bunn is the author of several books and numerous articles on the colonial-era, antebellum, and Civil War South, which give particular attention to its numerous historic sites. Material for this article was taken from his forthcoming history and guide to Alabama’s territorial and early statehood years, to be published by the University of Alabama Press. Bunn lives in Daphne, Alabama, with his wife, Tonya, and daughter, Zoey.

Additional Information

For more on Alabama’s boundaries, see http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-160

LAND CLAIMS AND SURVEYING IN THE ALABAMA TERRITORY

by Herbert James Lewis

As Native Americans were displaced from their historic lands, the area that would become the Alabama Territory was opened to settlement by Europeans and white Americans. Although legislation such as the Land Act of 1800 attempted to instill a kind of order to the settlement, the reality often differed. Many would be settlers simply claimed some acreage by squatting on it and starting to make improvements. Such circumstances underscored the need for official surveys to determine land tracts and establish clear ownership of them.

About the Author

Herbert James “Jim” Lewis earned both his BA in history and his law degree from the University of Alabama. He clerked at the Alabama Supreme Court, served in the US Air Force in the Judge Advocate General’s Office, and practiced law for twenty-six years as an Assistant US Attorney in Birmingham, Alabama. The Alabama Review published his 2006 article concerning one of Alabama’s earliest attorneys, Henry Wilbourne Stevens. For two years, Lewis edited or contributed numerous entries to the award-winning online Encyclopedia of Alabama. In March 2013 Quid Pro Books of New Orleans published his first book, Clearing the Thickets: A History of Antebellum Alabama. Jim’s second book, Lost Capitals of Alabama, was published by the History Press in November 2014. Lewis currently serves on the board of directors of the Alabama Historical Association, as well as the board of directors of the Shelby County Historical Society.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Timeline of 1801—1860: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1801.html

Creek War 1813-1814: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1820

Alabama Fever: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3155

John Coffee: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3041

by Herbert James Lewis

As Native Americans were displaced from their historic lands, the area that would become the Alabama Territory was opened to settlement by Europeans and white Americans. Although legislation such as the Land Act of 1800 attempted to instill a kind of order to the settlement, the reality often differed. Many would be settlers simply claimed some acreage by squatting on it and starting to make improvements. Such circumstances underscored the need for official surveys to determine land tracts and establish clear ownership of them.

About the Author

Herbert James “Jim” Lewis earned both his BA in history and his law degree from the University of Alabama. He clerked at the Alabama Supreme Court, served in the US Air Force in the Judge Advocate General’s Office, and practiced law for twenty-six years as an Assistant US Attorney in Birmingham, Alabama. The Alabama Review published his 2006 article concerning one of Alabama’s earliest attorneys, Henry Wilbourne Stevens. For two years, Lewis edited or contributed numerous entries to the award-winning online Encyclopedia of Alabama. In March 2013 Quid Pro Books of New Orleans published his first book, Clearing the Thickets: A History of Antebellum Alabama. Jim’s second book, Lost Capitals of Alabama, was published by the History Press in November 2014. Lewis currently serves on the board of directors of the Alabama Historical Association, as well as the board of directors of the Shelby County Historical Society.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Timeline of 1801—1860: http://www.archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1801.html

Creek War 1813-1814: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1820

Alabama Fever: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3155

John Coffee: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3041

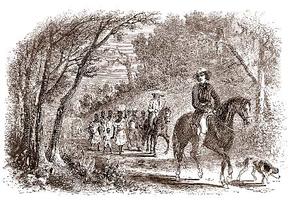

Wealthy planters brought their slaves and wagonloads of possessions with them when they moved to the frontier. (Public Domain)

Wealthy planters brought their slaves and wagonloads of possessions with them when they moved to the frontier. (Public Domain)

ALABAMA FEVER RAGES:

MIGRATIONS TO THE FRONTIER OF

EARLY ALABAMA

by Thomas Chase Hagood

As the Alabama Territory opened up to settlement, so many people migrated to the area that the phenomenon became known as Alabama Fever. The influx remains documented through letters, journals, and other accounts, and these texts indicate that the fever struck a wide range of people, from bachelors and families to elderly mothers reluctant to send their children to start a new life across the frontier. Even fabled frontiersman Davy Crockett ventured into the Alabama Territory, giving rise to sensational (and perhaps somewhat sensationalized) accounts of his adventures there.

About the Author

Thomas Chase Hagood serves as the director of the division of academic enhancement at the University of Georgia (UGA) where he directs programs and initiatives that foster students’ academic success. He is co-director of the university’s “Reacting to the Past” program. Hagood completed his PhD in history (May 2011) at UGA and began his academic career as an assistant professor of history and rural studies at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton, Georgia. Hagood’s passion for innovative instruction saw his return to UGA in fall 2013, joining the UGA Center for Teaching and Learning as an assistant director. Hagood’s historical research explores nineteenth-century America and American identity formation. His scholarship has been featured in The Southern Quarterly, The Alabama Review, The Journal of Backcountry Studies, and SouthernSpaces.org. Hagood is the co-editor of a forthcoming book on active-learning strategies and Reacting to the Past. For more on Hagood, see thomaschasehagood.com.

Additional Information

For more information, please see http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3155

MIGRATIONS TO THE FRONTIER OF

EARLY ALABAMA

by Thomas Chase Hagood

As the Alabama Territory opened up to settlement, so many people migrated to the area that the phenomenon became known as Alabama Fever. The influx remains documented through letters, journals, and other accounts, and these texts indicate that the fever struck a wide range of people, from bachelors and families to elderly mothers reluctant to send their children to start a new life across the frontier. Even fabled frontiersman Davy Crockett ventured into the Alabama Territory, giving rise to sensational (and perhaps somewhat sensationalized) accounts of his adventures there.

About the Author

Thomas Chase Hagood serves as the director of the division of academic enhancement at the University of Georgia (UGA) where he directs programs and initiatives that foster students’ academic success. He is co-director of the university’s “Reacting to the Past” program. Hagood completed his PhD in history (May 2011) at UGA and began his academic career as an assistant professor of history and rural studies at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton, Georgia. Hagood’s passion for innovative instruction saw his return to UGA in fall 2013, joining the UGA Center for Teaching and Learning as an assistant director. Hagood’s historical research explores nineteenth-century America and American identity formation. His scholarship has been featured in The Southern Quarterly, The Alabama Review, The Journal of Backcountry Studies, and SouthernSpaces.org. Hagood is the co-editor of a forthcoming book on active-learning strategies and Reacting to the Past. For more on Hagood, see thomaschasehagood.com.

Additional Information

For more information, please see http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3155

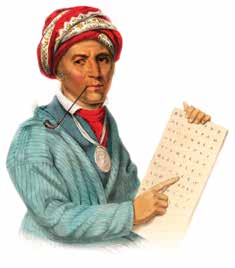

Sequoyah, a Cherokee, created the first written language for an American tribe. He lived in Wills Town during the Territorial period. (Library of Congress)

Sequoyah, a Cherokee, created the first written language for an American tribe. He lived in Wills Town during the Territorial period. (Library of Congress)

THE ALABAMA TERRITORY’S CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

by Gregory A. Waselkov

As Alabama Fever swept across the nation, the people racing into the Alabama Territory brought new kinds of housing, settlement, and agriculture—and they dramatically reshaped the area’s natural and social environments. The land itself was altered by deforestation and the introduction of non-native species, causing changes in the region’s wildlife populations. As settlers sought new means of transportation, roads and rivers were transformed. Native communities were overtaken by plantations, towns, and forts. Ecologically and socially, the area changed dramatically as the territory moved toward statehood.

About the Author

Gregory A. Waselkov has taught archaeology at the University of South Alabama for twenty-nine years, following nine years as a researcher at Auburn University. His interests in French Colonial America led to excavations at Fort Toulouse, Old Mobile, and several plantation sites along the Gulf Coast. His other primary research topic involves the Creek Indians in Alabama, which led to excavations at the Creek War battle sites of Fort Mims and Holy Ground. He is currently working on a book about religious revitalization movements in the Southeast between 1590 and 1813.

Additional Information

For more information on the history and culture of Alabama, during the territorial period and beyond, you may wish to visit the Museum of Alabama. http://www.museum.alabama.gov

by Gregory A. Waselkov

As Alabama Fever swept across the nation, the people racing into the Alabama Territory brought new kinds of housing, settlement, and agriculture—and they dramatically reshaped the area’s natural and social environments. The land itself was altered by deforestation and the introduction of non-native species, causing changes in the region’s wildlife populations. As settlers sought new means of transportation, roads and rivers were transformed. Native communities were overtaken by plantations, towns, and forts. Ecologically and socially, the area changed dramatically as the territory moved toward statehood.

About the Author

Gregory A. Waselkov has taught archaeology at the University of South Alabama for twenty-nine years, following nine years as a researcher at Auburn University. His interests in French Colonial America led to excavations at Fort Toulouse, Old Mobile, and several plantation sites along the Gulf Coast. His other primary research topic involves the Creek Indians in Alabama, which led to excavations at the Creek War battle sites of Fort Mims and Holy Ground. He is currently working on a book about religious revitalization movements in the Southeast between 1590 and 1813.

Additional Information

For more information on the history and culture of Alabama, during the territorial period and beyond, you may wish to visit the Museum of Alabama. http://www.museum.alabama.gov

In this 2009 photo, the half-cellar of the Globe Hotel can be seen behind the wooden framework. In the foreground are the foundations of the slave quarters. (Robin McDonald)

In this 2009 photo, the half-cellar of the Globe Hotel can be seen behind the wooden framework. In the foreground are the foundations of the slave quarters. (Robin McDonald)

ST. STEPHENS:

THE ALABAMA TERRITORY’S FIRST CAPITAL

by George Shorter

Originally created as a fort, St. Stephens changed hands between numerous nations before finally becoming the Alabama Territory’s first capital. Prior to that, it had been a trading post, a post office, a judicial seat, and a commercial center. It also held Alabama’s first school for settlers, which was established prior to the Alabama Territory. Although St. Stephens’s time as the capital was short lived, the town expanded for several years, until larger population centers lured most residents away. Today, St. Stephens is an active and vibrant archaeological site, discussed in depth in the sidebar to this article.

About the Author

George Shorter received a BS in landscape architecture in 1967 from Louisiana State University (LSU) and practiced for almost thirty years in Mobile. Returning to LSU in 1992, he received a MA in anthropology in 1995 and was employed by the Center for Archaeological Studies at the University of South Alabama as a research associate from that date until his retirement in 2013. During that period, he supervised numerous archaeological research projects dealing with prehistory as well as historical sites. In 1997 Shorter started his research at the historic site of Old St. Stephens in Washington County, Alabama. Since retirement he has continued to direct research at Old St. Stephens with the support of the center and its director, Dr. Gregory Waselkov, and the St. Stephens Historical Commission.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Old St. Stephens http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1674

St. Stephens Website: http://www.oldststephens.net/

William Wyatt Bibb: http://www.archives.state.al.us/govs_list/g_bibbwm.html

THE ALABAMA TERRITORY’S FIRST CAPITAL

by George Shorter

Originally created as a fort, St. Stephens changed hands between numerous nations before finally becoming the Alabama Territory’s first capital. Prior to that, it had been a trading post, a post office, a judicial seat, and a commercial center. It also held Alabama’s first school for settlers, which was established prior to the Alabama Territory. Although St. Stephens’s time as the capital was short lived, the town expanded for several years, until larger population centers lured most residents away. Today, St. Stephens is an active and vibrant archaeological site, discussed in depth in the sidebar to this article.

About the Author

George Shorter received a BS in landscape architecture in 1967 from Louisiana State University (LSU) and practiced for almost thirty years in Mobile. Returning to LSU in 1992, he received a MA in anthropology in 1995 and was employed by the Center for Archaeological Studies at the University of South Alabama as a research associate from that date until his retirement in 2013. During that period, he supervised numerous archaeological research projects dealing with prehistory as well as historical sites. In 1997 Shorter started his research at the historic site of Old St. Stephens in Washington County, Alabama. Since retirement he has continued to direct research at Old St. Stephens with the support of the center and its director, Dr. Gregory Waselkov, and the St. Stephens Historical Commission.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Old St. Stephens http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1674

St. Stephens Website: http://www.oldststephens.net/

William Wyatt Bibb: http://www.archives.state.al.us/govs_list/g_bibbwm.html

A pot of sofkee-nitkee with deer jerky cooks by an open fire.

A pot of sofkee-nitkee with deer jerky cooks by an open fire.

THE THREE SISTERS:

HOW SQUASH, BEANS, AND CORN BECAME SOUTHERN FOOD

by John C. Hall and Rosa N. Hall

Ask many people today to name southern foods, and you’ll likely get a fairly standard set of answers. What may be less recognizable is the origin of many of these food items that are now standard southern fare. John and Rosa Hall describe many delicacies and explore how they entered the southern belly from a range of sources, including Native American, European, and African communities.

About the Authors

John C. Hall was a frequent contributor to Alabama Heritage magazine. He has written articles on Hernando de Soto, William Bartram, Prince Madoc, and the Sylacauga Meteorite. He served as a naturalist at the Alabama Museum of Natural History and also as director of the Black Belt Museum at the University of West Alabama. With environmental photographer Beth Maynor Young, he was the coauthor of Headwaters, a Journey on Alabama Rivers (University of Alabama Press, 2009). He was also an author credited for Longleaf: As Far as the Eye Can See (University of North Carolina Press, 2012). He passed away in 2016 and is dearly missed by his family, friends, and colleagues. Alabama Heritage thanks him for his contributions to this magazine, our state, and the history community.

Rosa Newman Hall retired from the Alabama Museum of Natural History after doing programs and serving as the camp director for the Museum Expedition program, started by her late husband Dr. John Hall in 1979. The Museum Expedition will celebrate its thirty-ninth year this year at Old Cahawba. For over twenty years, she has performed living history programs as a Creek woman from the 1800s at museums and festivals all over the Southeast. With a hunting camp set up, she demonstrates cooking, discusses foods, highlights the woman’s role in the society, as well as describes the deer skin trade and how it affected the Creek Nation. Hall currently performs similar activities at the University of West Alabama with The Center for the Study of the Black Belt.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Native American Foods: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2150

Archaic Period: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1163

“Busk” or Green Corn Ceremony: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1553

HOW SQUASH, BEANS, AND CORN BECAME SOUTHERN FOOD

by John C. Hall and Rosa N. Hall

Ask many people today to name southern foods, and you’ll likely get a fairly standard set of answers. What may be less recognizable is the origin of many of these food items that are now standard southern fare. John and Rosa Hall describe many delicacies and explore how they entered the southern belly from a range of sources, including Native American, European, and African communities.

About the Authors

John C. Hall was a frequent contributor to Alabama Heritage magazine. He has written articles on Hernando de Soto, William Bartram, Prince Madoc, and the Sylacauga Meteorite. He served as a naturalist at the Alabama Museum of Natural History and also as director of the Black Belt Museum at the University of West Alabama. With environmental photographer Beth Maynor Young, he was the coauthor of Headwaters, a Journey on Alabama Rivers (University of Alabama Press, 2009). He was also an author credited for Longleaf: As Far as the Eye Can See (University of North Carolina Press, 2012). He passed away in 2016 and is dearly missed by his family, friends, and colleagues. Alabama Heritage thanks him for his contributions to this magazine, our state, and the history community.

Rosa Newman Hall retired from the Alabama Museum of Natural History after doing programs and serving as the camp director for the Museum Expedition program, started by her late husband Dr. John Hall in 1979. The Museum Expedition will celebrate its thirty-ninth year this year at Old Cahawba. For over twenty years, she has performed living history programs as a Creek woman from the 1800s at museums and festivals all over the Southeast. With a hunting camp set up, she demonstrates cooking, discusses foods, highlights the woman’s role in the society, as well as describes the deer skin trade and how it affected the Creek Nation. Hall currently performs similar activities at the University of West Alabama with The Center for the Study of the Black Belt.

Additional Information

For additional information, please consult the following:

Native American Foods: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2150

Archaic Period: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1163

“Busk” or Green Corn Ceremony: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1553

DEPARTMENT ABSTRACTS

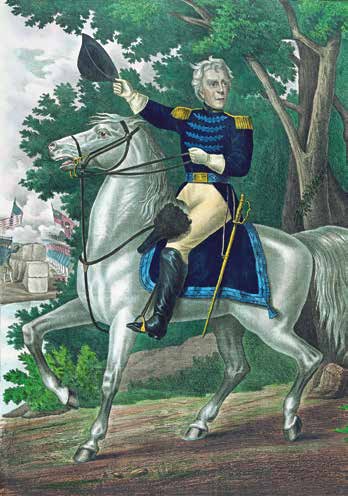

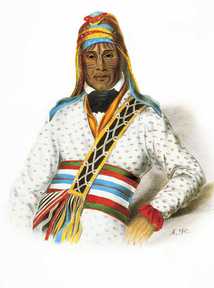

The Upper Creek chief Yoholo Micco fought with the Americans in the Creek War and signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson, yet he died at age fifty during the enforced removal of the Creeks from Alabama west to the Indian Territory.

(McKenney and Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America)

The Upper Creek chief Yoholo Micco fought with the Americans in the Creek War and signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson, yet he died at age fifty during the enforced removal of the Creeks from Alabama west to the Indian Territory.

(McKenney and Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America)

The Alabama Territory

Quarter by Quarter

Editor’s Note--Alabama Heritage, the Alabama Bicentennial Commission, and the Alabama Tourism Department offer this serialized history of Alabama’s road to statehood as part of Alabama’s bicentennial celebrations that will run from 2017 through 2019. Quarter by Quarter allows you to experience the story of the territorial era as it unfolds, ultimately culminating in Alabama’s acceptance into the Union as a state—sometimes describing pivotal events, sometimes describing daily life, but always illuminating a world in flux. We will wait for the outcomes as our forebears did—over time. If you would like to follow the story online, you can find earlier quarters on our website at www.AlabamaHeritage.com.

Abstract

Alabama’s territorial identity was shaped by the Mississippi bid for statehood. The Mississippi Territory, which originally included what is now the state of Alabama, was divided to expedite Mississippi’s acceptance into the union, and Alabama’s own quick path to statehood soon followed.

About the Author

Mike Bunn currently serves as director of operations at Historic Blakeley State Park in Spanish Fort, Alabama. This department of Alabama Heritage magazine is sponsored by the Alabama Bicentennial Commission and the Alabama Tourism Department.

Quarter by Quarter

Editor’s Note--Alabama Heritage, the Alabama Bicentennial Commission, and the Alabama Tourism Department offer this serialized history of Alabama’s road to statehood as part of Alabama’s bicentennial celebrations that will run from 2017 through 2019. Quarter by Quarter allows you to experience the story of the territorial era as it unfolds, ultimately culminating in Alabama’s acceptance into the Union as a state—sometimes describing pivotal events, sometimes describing daily life, but always illuminating a world in flux. We will wait for the outcomes as our forebears did—over time. If you would like to follow the story online, you can find earlier quarters on our website at www.AlabamaHeritage.com.

Abstract

Alabama’s territorial identity was shaped by the Mississippi bid for statehood. The Mississippi Territory, which originally included what is now the state of Alabama, was divided to expedite Mississippi’s acceptance into the union, and Alabama’s own quick path to statehood soon followed.

About the Author

Mike Bunn currently serves as director of operations at Historic Blakeley State Park in Spanish Fort, Alabama. This department of Alabama Heritage magazine is sponsored by the Alabama Bicentennial Commission and the Alabama Tourism Department.