|

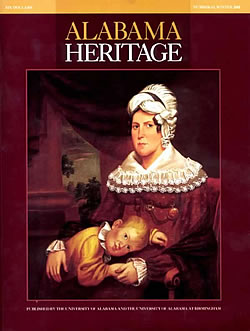

On the cover: John Grimes's portrait of Parmelia Thompson Bibb, 1784-1854, wife of Gov. Thomas Bibb, with her son.

|

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

John Grimes: Alabama's First Portrait Artist

By Edward Patillo

Alabama was once the rough frontier of our nation, but to the citizens of early Huntsville, having a portrait painter in town added a touch of civilization to the wilderness. That painter, John Grimes, left behind a body of stunning work that provides an insightful glimpse at the earliest citizens of the state. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, Edward Patillo follows the life of Grimes, from his early days as a student of painter Matthew Harris Jouett, to his timely arrival in Alabama where he made a name for himself. Huntsville was then ambitious and new, and Grimes painted its leading citizens. In addition to biographical information, stunning photographs of Grimes' work accompany the article, including renderings of his earliest paintings and his later, more developed style. These beautiful portraits show the richness of the artist's talent and offer an enlightening look at the earliest upper class in Alabama.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:Multimedia:

About the Author

Edward Patillo is a frequent contributor to Alabama Heritage. Most recently, he has written a piece on Paris porcelain in antebellum Alabama. An alumnus of the University of Alabama and Columbia University, Pattillo is currently an active appraiser of personal property and a consultant for the museums and the history program of the new Federal Judicial Building in Montgomery.

The author wishes to thank Jack and Emily Burwell of Huntsville, who made available their transcriptions of "The Old Mahogany Table" articles by Virginia Clay; John Rison Jones, Huntsville; Mr. and Mrs. Ben Walker, Huntsville; Mrs. Dixon Barr, Lexington, Kentucky; the late William Barrow Floyd, Lexington, the biographer of Matthew Harris Jouett; the Tennessee Historical Society; and the owners of the paintings.

By Edward Patillo

Alabama was once the rough frontier of our nation, but to the citizens of early Huntsville, having a portrait painter in town added a touch of civilization to the wilderness. That painter, John Grimes, left behind a body of stunning work that provides an insightful glimpse at the earliest citizens of the state. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, Edward Patillo follows the life of Grimes, from his early days as a student of painter Matthew Harris Jouett, to his timely arrival in Alabama where he made a name for himself. Huntsville was then ambitious and new, and Grimes painted its leading citizens. In addition to biographical information, stunning photographs of Grimes' work accompany the article, including renderings of his earliest paintings and his later, more developed style. These beautiful portraits show the richness of the artist's talent and offer an enlightening look at the earliest upper class in Alabama.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:Multimedia:

About the Author

Edward Patillo is a frequent contributor to Alabama Heritage. Most recently, he has written a piece on Paris porcelain in antebellum Alabama. An alumnus of the University of Alabama and Columbia University, Pattillo is currently an active appraiser of personal property and a consultant for the museums and the history program of the new Federal Judicial Building in Montgomery.

The author wishes to thank Jack and Emily Burwell of Huntsville, who made available their transcriptions of "The Old Mahogany Table" articles by Virginia Clay; John Rison Jones, Huntsville; Mr. and Mrs. Ben Walker, Huntsville; Mrs. Dixon Barr, Lexington, Kentucky; the late William Barrow Floyd, Lexington, the biographer of Matthew Harris Jouett; the Tennessee Historical Society; and the owners of the paintings.

Daniel S. Troy, 1887

Daniel S. Troy, 1887(Troy Family)

Incident at Hatcher's Run

By Sam Duvall

In the final days of the Civil War, Colonel D. S. Troy, C.S.A., was attempting to reform his lines in a battle near Petersburg, Virginia, when he was shot by a Union private. Troy survived the wound-which he thought was fatal-and told a tale of surprising humanity in times of war. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, Sam Duvall tells how Colonel Troy was captured and transported to a field hospital, where he received compassionate care from his captors throughout his recovery. In the article, Duvall refers to the journals of the men who participated in the skirmish and paints a vivid description of the scene from both Union and Confederate perspectives. He also relates how the story of Colonel Troy is intertwined with that of George W. Thompkins, the Union private who nearly killed him. Most amazing is the story of how, in 1923, Colonel Troy's son was able to contact Thompkins, telling him that the Colonel had indeed survived the wound Thompkins inflicted-news which reportedly pleased the Union veteran very much.

Additional Information

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Sam Duvall is the Communications Director for the Alabama Forestry Association, where he handles the publication of a quarterly full-color magazine and a monthly newsletter, plus other non-deadline publications for the association. His article on World War II pilot Ray Davis appeared in Alabama Heritage #59.

He would like to thank Bill Schaum, a Montgomery videographer and great-grandson of D. S. Troy, who provided him with a copy of Col. Troy's reminiscence, and Marie Troy from Montgomery, great-granddaughter of the Colonel, who read the article and provided valuable input. In addition, he wishes to thank Mr. John Troy of Muscle Shoals, the grandson of D. S. Troy, who has lovingly cared for the Colonel's sash and allowed it to be photographed for this article. Duvall would also like to thank Charles J. "Chuck" LaRocca of New York, who provided information on the Hatcher's Run Battle from a regimental history of the 124th New York Volunteers. LaRocca serves as a captain in the 124th New

York Volunteers reenactment unit.

By Sam Duvall

In the final days of the Civil War, Colonel D. S. Troy, C.S.A., was attempting to reform his lines in a battle near Petersburg, Virginia, when he was shot by a Union private. Troy survived the wound-which he thought was fatal-and told a tale of surprising humanity in times of war. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, Sam Duvall tells how Colonel Troy was captured and transported to a field hospital, where he received compassionate care from his captors throughout his recovery. In the article, Duvall refers to the journals of the men who participated in the skirmish and paints a vivid description of the scene from both Union and Confederate perspectives. He also relates how the story of Colonel Troy is intertwined with that of George W. Thompkins, the Union private who nearly killed him. Most amazing is the story of how, in 1923, Colonel Troy's son was able to contact Thompkins, telling him that the Colonel had indeed survived the wound Thompkins inflicted-news which reportedly pleased the Union veteran very much.

Additional Information

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

- Alabama and the Civil War (feature)

- Civil War in Alabama

- Civil War Amputation Kit (image)

- Troy

About the Author

Sam Duvall is the Communications Director for the Alabama Forestry Association, where he handles the publication of a quarterly full-color magazine and a monthly newsletter, plus other non-deadline publications for the association. His article on World War II pilot Ray Davis appeared in Alabama Heritage #59.

He would like to thank Bill Schaum, a Montgomery videographer and great-grandson of D. S. Troy, who provided him with a copy of Col. Troy's reminiscence, and Marie Troy from Montgomery, great-granddaughter of the Colonel, who read the article and provided valuable input. In addition, he wishes to thank Mr. John Troy of Muscle Shoals, the grandson of D. S. Troy, who has lovingly cared for the Colonel's sash and allowed it to be photographed for this article. Duvall would also like to thank Charles J. "Chuck" LaRocca of New York, who provided information on the Hatcher's Run Battle from a regimental history of the 124th New York Volunteers. LaRocca serves as a captain in the 124th New

York Volunteers reenactment unit.

Old Mobile Archaeology

By Gregory A. Waselkov

The year 2002 marks the three hundredth anniversary of the year Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville sailed up the Mobile River to a spot now known as Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff and established a settlement there named Mobile. In conjunction with the City of Mobile's Tricentennial Celebration, Alabama Heritage looks back at the founding of the city through its archaeology. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, Gregory A. Waselkov tells the story of the decision to establish a settlement up the Mobile River, and how the colony was later moved further south to Mobile Bay. Left behind at the Old Mobile site are tantalizingly brief clues about early colonial life in Alabama. Waselkov guides an archaeological tour through the remains of Old Mobile, providing a unique-and often unexpected-glimpse at the first Alabama colonists and their possessions. His article explains the process of digging up history and gives the most complete understanding of the state's elusive earliest settlement.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

About the Author

Gregory A. Waselkov professor of anthropology and director of the Center for Archaeological Studies at the University of South Alabama in Mobile, has studied the Indians and the French of the colonial southeast for over two decades. To learn more about archaeology in the Mobile area, see Waselkov's booklet, Old Mobile Archaeology (University of

South Alabama, 1999), or visit the "Old Mobile Archaeology" website.

By Gregory A. Waselkov

The year 2002 marks the three hundredth anniversary of the year Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville sailed up the Mobile River to a spot now known as Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff and established a settlement there named Mobile. In conjunction with the City of Mobile's Tricentennial Celebration, Alabama Heritage looks back at the founding of the city through its archaeology. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, Gregory A. Waselkov tells the story of the decision to establish a settlement up the Mobile River, and how the colony was later moved further south to Mobile Bay. Left behind at the Old Mobile site are tantalizingly brief clues about early colonial life in Alabama. Waselkov guides an archaeological tour through the remains of Old Mobile, providing a unique-and often unexpected-glimpse at the first Alabama colonists and their possessions. His article explains the process of digging up history and gives the most complete understanding of the state's elusive earliest settlement.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

Multimedia:

About the Author

Gregory A. Waselkov professor of anthropology and director of the Center for Archaeological Studies at the University of South Alabama in Mobile, has studied the Indians and the French of the colonial southeast for over two decades. To learn more about archaeology in the Mobile area, see Waselkov's booklet, Old Mobile Archaeology (University of

South Alabama, 1999), or visit the "Old Mobile Archaeology" website.

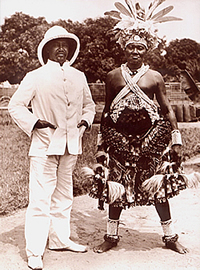

William Sheppard with

William Sheppard withthe chief of the Ibanche people

(Presbyterian Historical Society,

Presbyterian Church, U.S.A.,

Montreat, NC)

Changing the Heart of Darkness: Sheppard and Lapsley in the Congo

By T.J. Beitelman

In 1890, the work of spreading religion to foreign lands was often perilous and risky at best. But for an unlikely duo of Southern Presbyterian missionaries-one the son of former slaves, the other kin to former slave owners-peril and risk spelled the chance of a lifetime. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, T. J. Beitelman tells the story of Samuel Lapsley, a white minister, and William Sheppard, a black minister, who were joined together by the Southern Presbyterian Church to spread Christianity through the African continent. Sheppard and Lapsley would soon discover that their differences had the strange quality of fitting together like cogs in a machine. One supplied what the other lacked. Through letters and journals written by the two men, Beitelman follows the missionaries throughout their African mission work, including Lapsley's bout with "bilious fever," which he eventually succumbed to, leaving Sheppard alone. Sheppard continued his work for many years, finally returning home in his old age to be welcomed with a measure of celebrity-and bringing with him a story of faith, friendship, and adventure.

Additional Information

About the Author

T.J. Beitelman is associate editor of Alabama Heritage. He holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing from the University of Alabama and a Master of Arts degree in English literature from Virginia Tech. Prior to coming to Alabama Heritage, he edited Black Warrior Review, a nationally acclaimed literary magazine published at the University of Alabama. He wishes to thank the Presbyterian Historical Society in Montreat, North Carolina, and

Robert Heath, Dean for Stillman College's Sheppard Library, for their invaluable assistance with this article.

By T.J. Beitelman

In 1890, the work of spreading religion to foreign lands was often perilous and risky at best. But for an unlikely duo of Southern Presbyterian missionaries-one the son of former slaves, the other kin to former slave owners-peril and risk spelled the chance of a lifetime. In the Winter 2002 issue of Alabama Heritage, T. J. Beitelman tells the story of Samuel Lapsley, a white minister, and William Sheppard, a black minister, who were joined together by the Southern Presbyterian Church to spread Christianity through the African continent. Sheppard and Lapsley would soon discover that their differences had the strange quality of fitting together like cogs in a machine. One supplied what the other lacked. Through letters and journals written by the two men, Beitelman follows the missionaries throughout their African mission work, including Lapsley's bout with "bilious fever," which he eventually succumbed to, leaving Sheppard alone. Sheppard continued his work for many years, finally returning home in his old age to be welcomed with a measure of celebrity-and bringing with him a story of faith, friendship, and adventure.

Additional Information

- Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Houghton Mifflin, 1998).

- Jacobs, Sylvia, ed. Black Americans and the Missionary Movement in Africa (Greenwood Press, 1982).

- Lapley, Samuel Norvell. Life and Letters of Samuel Norvell Lapsley, Missionary to the Congo Valley, West Africa, 1866-1892 (Whittet & Shepperson, 1893).

- Sheppard, William Henry. Presbyterian Pioneers in Congo (Presbyterian Committee of Publications, 1916).

About the Author

T.J. Beitelman is associate editor of Alabama Heritage. He holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing from the University of Alabama and a Master of Arts degree in English literature from Virginia Tech. Prior to coming to Alabama Heritage, he edited Black Warrior Review, a nationally acclaimed literary magazine published at the University of Alabama. He wishes to thank the Presbyterian Historical Society in Montreat, North Carolina, and

Robert Heath, Dean for Stillman College's Sheppard Library, for their invaluable assistance with this article.

DEPARTMENT ABSTRACT

A liverleaf in Jefferson County

A liverleaf in Jefferson County(L.J. Davenport)

The Nature Album

Liverleaf (And the Doctrine of Signatures)

By L. J. Davenport

Compared to its more spectacular springtime colleagues, liverleaf (or hepatica) appears none too special--jut a few white, pink, or lavender blooms popping up through mottled, coppery leaves left over from the previous years. But those leaves possess "powers" unparalleled in the botanical world. L.J. Davenport examines the history and nature of this remarkable plant.

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

Liverleaf (And the Doctrine of Signatures)

By L. J. Davenport

Compared to its more spectacular springtime colleagues, liverleaf (or hepatica) appears none too special--jut a few white, pink, or lavender blooms popping up through mottled, coppery leaves left over from the previous years. But those leaves possess "powers" unparalleled in the botanical world. L.J. Davenport examines the history and nature of this remarkable plant.

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.