|

On the cover: William Frye's "Vue of the

Huntsville Spring from Nature," c. 1845. (Courtesy Wamm Rhett/Photograph by Robin McDonald) |

FEATURE ABSTRACTS

Montgomery historian Richard Bailey holds the 1901 Constitution in a photo that appeared on October 15, 2000, in the first of seven Mobile Register editorials titled, "Alabama's Constitution: Century of Shame." (Courtesy of the Mobile Register 2000)

Montgomery historian Richard Bailey holds the 1901 Constitution in a photo that appeared on October 15, 2000, in the first of seven Mobile Register editorials titled, "Alabama's Constitution: Century of Shame." (Courtesy of the Mobile Register 2000)

Why Alabama Needs a New Constitution

By Albert P. Brewer

Alabama's constitution is the longest in the world, more than forty times as long as the US Constitution, and longer even than Moby Dick. The state's charter has been amended 706 times, for reasons as general as changing statewide school spending and as specific as allowing Mobile County to start a mosquito control program. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, former Governor Albert P. Brewer outlines the case for abandoning Alabama's current constitution and writing a new one from scratch. He explains how the present constitution's provisions for an unstable tax structure, limited home rule, and restricted public spending impose needless handicaps on local governments, businesses, and citizens. With Alabama's constitution celebrating its one hundredth birthday this year, Brewer's words come at a particularly appropriate time in the hot debate on constitutional reform.

Additional Information

About the Author

Albert Preston Brewer served as governor of Alabama from 1968 to 1971, succeeding Gov. Lurleen Wallace who died in office. A graduate of the University of Alabama and the University of Alabama School of Law, Brewer practiced law in Decatur, Alabama, and in 1954 entered the state legislature. He is the only person in Alabama history to serve as speaker of the house, lieutenant governor, and governor. Brewer is presently Distinguished Professor of Law and Government at Samford University's Cumberland School of Law. As governor, he supported constitutional reform in Alabama, a subject he continues to research and on which he writes and speaks often.

By Albert P. Brewer

Alabama's constitution is the longest in the world, more than forty times as long as the US Constitution, and longer even than Moby Dick. The state's charter has been amended 706 times, for reasons as general as changing statewide school spending and as specific as allowing Mobile County to start a mosquito control program. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, former Governor Albert P. Brewer outlines the case for abandoning Alabama's current constitution and writing a new one from scratch. He explains how the present constitution's provisions for an unstable tax structure, limited home rule, and restricted public spending impose needless handicaps on local governments, businesses, and citizens. With Alabama's constitution celebrating its one hundredth birthday this year, Brewer's words come at a particularly appropriate time in the hot debate on constitutional reform.

Additional Information

- Grafton, Carl and Anne Permaloff. Big Mules and Branchheads: James E. Folsom and Political Power in Alabama (The University of Georgia Press, 1985).

- McMillan, Malcolm Cook. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism (The Reprint Company, Publishers, 1978).

- Moore, A. B. History of Alabama (Alabama Bookstore, 1951).

About the Author

Albert Preston Brewer served as governor of Alabama from 1968 to 1971, succeeding Gov. Lurleen Wallace who died in office. A graduate of the University of Alabama and the University of Alabama School of Law, Brewer practiced law in Decatur, Alabama, and in 1954 entered the state legislature. He is the only person in Alabama history to serve as speaker of the house, lieutenant governor, and governor. Brewer is presently Distinguished Professor of Law and Government at Samford University's Cumberland School of Law. As governor, he supported constitutional reform in Alabama, a subject he continues to research and on which he writes and speaks often.

Alabama's electric chair, "Yellow Mama"

Alabama's electric chair, "Yellow Mama"(Bettmann/CORBIS)

To Die in Dixie: Alabama and the Electric Chair

By Derryn E. Moten

This ought to shock you. Seventy-four years after electrocuting its first condemned prisoner in 1927, Alabama is one of the last states in the country to use the electric chair as its sole means of execution. Since that year, the state has put 175 individuals to death. An additional 190 on death row are currently waiting their turn--the seventh highest number of any state in the union. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, Derryn E. Moten investigates the gruesome history of electrocution as a form of capital punishment, and he explains the charged controversy that has surrounded the practice in Alabama from the beginning. From the invention of the electric chair by a New York dentist, to a technological rivalry between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse, to the construction of Alabama's "Yellow Mama" by a convicted burglar serving sixty years, Moten traces the bizarre course of Alabama's ultimate form of criminal justice.

Additional Information

About the Author

Derryn Moten holds a doctorate and a master's degree in American Studies from the University of Iowa, a MLS from the Catholic University of America, and a bachelor's degree in English from Howard University. His book on the August 16, 1912, execution of Virginia Christian, a seventeen-year-old black juvenile from Hampton, Virginia, is due out from the University of Georgia Press in Spring of 2002. He is currently Associate Professor of Humanities at Alabama State University in Montgomery.

The author and editors wish to extend thanks to the following individuals and organizations for their assistance with this article: the staff of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, particularly Rickie Brunner, Norwood Kerr, and Ken Tilley; Bryan Stevenson, LaJuana Davis, and Eva Ansley of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery; and Watt Espy.

By Derryn E. Moten

This ought to shock you. Seventy-four years after electrocuting its first condemned prisoner in 1927, Alabama is one of the last states in the country to use the electric chair as its sole means of execution. Since that year, the state has put 175 individuals to death. An additional 190 on death row are currently waiting their turn--the seventh highest number of any state in the union. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, Derryn E. Moten investigates the gruesome history of electrocution as a form of capital punishment, and he explains the charged controversy that has surrounded the practice in Alabama from the beginning. From the invention of the electric chair by a New York dentist, to a technological rivalry between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse, to the construction of Alabama's "Yellow Mama" by a convicted burglar serving sixty years, Moten traces the bizarre course of Alabama's ultimate form of criminal justice.

Additional Information

- Marquart, James W. The Rope, the Chair, and the Needle: Capital Punishment in Texas, 1923-1990 (The University of Texas Press, 1994).

- Miller, Arthur Selwyn. Death by Installments: The Ordeal of Willie Francis (Greenwood, 1998).

- Pennington, Michael and Nicholas O'Dwyer. The Chair (First Run/Icarus Films, 1998).

- Prejean, Helen. Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States (Random House, 1993).

About the Author

Derryn Moten holds a doctorate and a master's degree in American Studies from the University of Iowa, a MLS from the Catholic University of America, and a bachelor's degree in English from Howard University. His book on the August 16, 1912, execution of Virginia Christian, a seventeen-year-old black juvenile from Hampton, Virginia, is due out from the University of Georgia Press in Spring of 2002. He is currently Associate Professor of Humanities at Alabama State University in Montgomery.

The author and editors wish to extend thanks to the following individuals and organizations for their assistance with this article: the staff of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, particularly Rickie Brunner, Norwood Kerr, and Ken Tilley; Bryan Stevenson, LaJuana Davis, and Eva Ansley of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery; and Watt Espy.

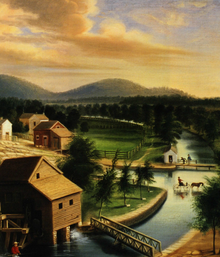

John Hunt, a pioneer squatter, turned north Alabama's Big Spring- painted here in its early days by William Frye- into a hub for a growing community of independent- minded frontiersmen like him. (Courtesy Warren Rhen, Photography by Robin McDonald)

John Hunt, a pioneer squatter, turned north Alabama's Big Spring- painted here in its early days by William Frye- into a hub for a growing community of independent- minded frontiersmen like him. (Courtesy Warren Rhen, Photography by Robin McDonald)

Twickenham: Or How Huntsville Came to Share Its History with a London Suburb

By John R. Jordan, Jr.

What's in a name? In Huntsville's case, you could start with greed, power, factionalism, and international politics. But that's just the beginning. In the early nineteenth century, the Tennessee River Valley attracted the attention of many men seeking freedom and fortune. Two of these individuals--a rugged homesteader named John Hunt and a moneyed plantation farmer named LeRoy Pope--would play key roles in the foundation of the area now known as Huntsville. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, John R. Jordan, Jr., describes the tenacious rivalry between these two men for the rights to own and name the budding settlement. How the town eventually came to be known as Huntsville, rather than Twickenham, as Pope had wished, is a revealing tale of their ugly struggle.

Additional Information

John Jordan grew up in Huntsville, a child of the Space Race. His technical roots led him to pursue his bachelor's degree in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Vanderbilt Univerity. He returned to the Huntsville area and joined a small military defense contractor, CAS, Inc., where he continues to work today as a Vice President and Technical Director in the Air and Missile Defense Group. Mr. Jordan earned a master's degree at the University of Alabama in Huntsville in Systems Engineering and a second master's degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in management. His love of international travel, especially in the British Isles, combined with a childhood fascination with Huntsville's early history provided the spark for his research into Huntsville's link with Twickenham, England.

By John R. Jordan, Jr.

What's in a name? In Huntsville's case, you could start with greed, power, factionalism, and international politics. But that's just the beginning. In the early nineteenth century, the Tennessee River Valley attracted the attention of many men seeking freedom and fortune. Two of these individuals--a rugged homesteader named John Hunt and a moneyed plantation farmer named LeRoy Pope--would play key roles in the foundation of the area now known as Huntsville. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, John R. Jordan, Jr., describes the tenacious rivalry between these two men for the rights to own and name the budding settlement. How the town eventually came to be known as Huntsville, rather than Twickenham, as Pope had wished, is a revealing tale of their ugly struggle.

Additional Information

- Betts, Edward Chambers. Early History of Huntsville, Alabama 1804-1870 (Old Huntsville, Inc., 1998).

- Carney, Tom. The Way It Was (the Other Side of Huntsville's Story) (Old Huntsville, Inc., 1994).

- Dupre, Daniel S. Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County Alabama 1800-1840 (Louisiana State

- University Press, 1997).

- Mack, Maynard. Alexander Pope: A Life (W. W. Norton & Co., 1985).

John Jordan grew up in Huntsville, a child of the Space Race. His technical roots led him to pursue his bachelor's degree in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Vanderbilt Univerity. He returned to the Huntsville area and joined a small military defense contractor, CAS, Inc., where he continues to work today as a Vice President and Technical Director in the Air and Missile Defense Group. Mr. Jordan earned a master's degree at the University of Alabama in Huntsville in Systems Engineering and a second master's degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in management. His love of international travel, especially in the British Isles, combined with a childhood fascination with Huntsville's early history provided the spark for his research into Huntsville's link with Twickenham, England.

Places in Peril 2001

By Brandon Brazil and Patrick McIntyre

What is it about historic neighborhoods that gives each one of them its own unique sense of place? Good planning might be the best answer. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, Brandon Brazil and Patrick McIntyre renew the magazine's popular annual "Places in Peril" feature, this time turning their focus on the concrete planning and legislation needed to preserve the unique character of Alabama's historic neighborhoods. "Keeping a historic neighborhood intact does not happen by chance," they write. "Successful local historic districts depend heavily on a committed and educated historic preservation commission that evenly applies design guidelines to regulate development." Their discussion is followed by a review of the state's most recent additions to the list of endangered historic landmarks. From the commercial encroachment on the elegant Sweetwater Plantation in Florence, to Opelika's Frederick House, which faces removal or demolition as the result of church expansion, ten new properties are described that now face the threat of loss.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Authors

Brandon Brazil is Preservation Issues Coordinator for the Alabama Historical Commission, while Patrick McIntyre serves as Endangered Properties Coordinator. As part of the Commission's Outreach and Development Division, they work across the state with concerned citizens, local municipalities, and civic organizations to develop preservation strategies. Special thanks goes to Mary Mason Shell of the Alabama

Historical Commission for her generous assistance with this article. The eighth annual listing of Places in Peril was prepared by Douglas Purcell , chair, and a committee of preservationists, archaeologists, and historians. David Nelson, Carole King, and Chip DeShields represented the Alabama Preservation Alliance. Robert Gamble, Patrick McIntyre, Elizabeth Brown, Brandon Brazil, Stacye Hathorn, and Greg Rhinehart represented the Alabama Historical Commission.

By Brandon Brazil and Patrick McIntyre

What is it about historic neighborhoods that gives each one of them its own unique sense of place? Good planning might be the best answer. In the Fall 2001 issue of Alabama Heritage, Brandon Brazil and Patrick McIntyre renew the magazine's popular annual "Places in Peril" feature, this time turning their focus on the concrete planning and legislation needed to preserve the unique character of Alabama's historic neighborhoods. "Keeping a historic neighborhood intact does not happen by chance," they write. "Successful local historic districts depend heavily on a committed and educated historic preservation commission that evenly applies design guidelines to regulate development." Their discussion is followed by a review of the state's most recent additions to the list of endangered historic landmarks. From the commercial encroachment on the elegant Sweetwater Plantation in Florence, to Opelika's Frederick House, which faces removal or demolition as the result of church expansion, ten new properties are described that now face the threat of loss.

Additional Information

The following articles in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

- Florence

- Opelika

- Plantation Architecture in Alabama

- Sweetwater Plantation, Lauderdale County (image)

About the Authors

Brandon Brazil is Preservation Issues Coordinator for the Alabama Historical Commission, while Patrick McIntyre serves as Endangered Properties Coordinator. As part of the Commission's Outreach and Development Division, they work across the state with concerned citizens, local municipalities, and civic organizations to develop preservation strategies. Special thanks goes to Mary Mason Shell of the Alabama

Historical Commission for her generous assistance with this article. The eighth annual listing of Places in Peril was prepared by Douglas Purcell , chair, and a committee of preservationists, archaeologists, and historians. David Nelson, Carole King, and Chip DeShields represented the Alabama Preservation Alliance. Robert Gamble, Patrick McIntyre, Elizabeth Brown, Brandon Brazil, Stacye Hathorn, and Greg Rhinehart represented the Alabama Historical Commission.

To read about more places in peril, click here for our Places in Peril blog.

DEPARTMENT ABSTRACT

A luna moth on a sweetgum trunk

A luna moth on a sweetgum trunk(W. Mike Howell)

The Nature Journal

"Luna Moths (And Pheromones)"

By L. J. Davenport

Luna moths do not eat; instead, they spend their single week of life seeking a mate. L.J. Davenport discusses the use of pheromones in the luna moth's mating cycle.

Additional Information

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham.

"Luna Moths (And Pheromones)"

By L. J. Davenport

Luna moths do not eat; instead, they spend their single week of life seeking a mate. L.J. Davenport discusses the use of pheromones in the luna moth's mating cycle.

Additional Information

The following items in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will also be of interest:

About the Author

Larry Davenport is a professor of biology at Samford University, Birmingham.