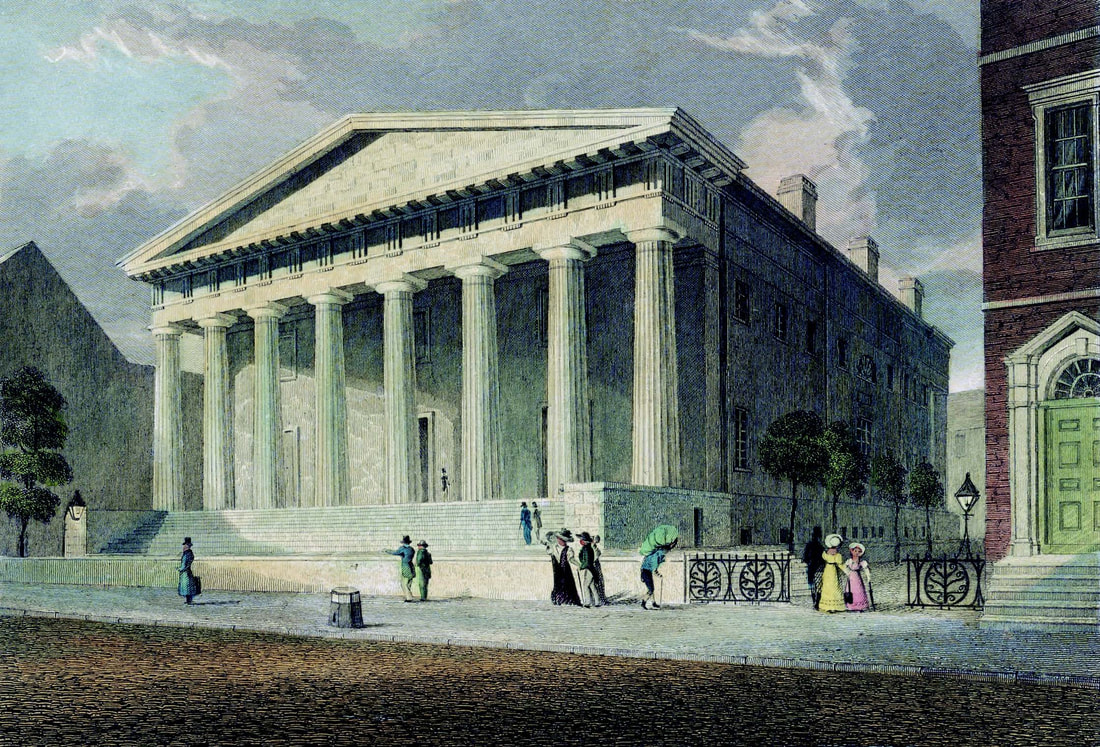

The tight money policies of the Second Bank of the United States, headquartered in Philadelphia (above), were blamed for the length and depth of the recession following the Panic of 1819, particularly in the South and West, where borrowed money was needed to buy land on the frontier. The loss of credit caused many Alabama landowners to default on their loans. (Library of Congress)

In many ways the year Alabama became a state stands as among the least auspicious of its tumultuous territorial experience. Shortly after the turn of the New Year in 1819, a land heretofore showcasing steady economic growth, generous and easy credit, wide-ranging speculation, and general optimism among a swelling population suddenly entered a severe economic downturn that threatened to reverse its previous progress. Known to historians as the Panic of 1819, this first major depression in US history struck Alabama particularly hard and carried far-ranging repercussions that resonated well into its first decade of statehood.

The root causes of the depression are tangled and complex, but it is generally agreed that at its heart lay a combination of overextension of credit in the heady years after the War of 1812, a rash of unregulated banking and questionable financial management of the Second Bank of the United States, lowered demand for cotton in Europe as it began to tap into Indian markets, and declining prices for manufactured goods. Alabama essentially became the front lines of the disaster in the South, as cotton and land sales financed by its fledgling banks were the very lifeblood of its economic engine. In early 1819 the first tremors of the impending calamity hit when cotton prices began to falter. By summer they had plummeted to twelve cents per pound after an extended period in which they averaged over twice that and at times had reached over thirty cents per pound. The cascading series of disasters that resulted brought widespread economic ruin over much of Alabama for an extended period, as shaken financial institutions stopped issuing loans and countless debtors suddenly defaulted on loans for the soil they tilled. The financial collapse unraveled the very fabric of frontier communities across the territory, as the informal and unregulated methods of extending credit and repaying debt—often sealed with little more than handshakes and letters of recommendation obligating friends and family as security on loans—collapsed on itself like so many dominoes and swamped communities in wholesale fashion. By some estimates as much as half the nation’s land debt lay in Alabama at the onset of the panic, and debtors ended up relinquishing enormous swaths of acreage. In the Huntsville area alone, the federal government reclaimed some 400,000 acres within three years. Reactions to the setbacks ranged from fleeing the scene to suicide.

The panic’s repercussions extended far beyond the purely economic realm in Alabama. In some ways it redefined the political landscape, since in finding a scapegoat for the calamity Alabamians believed they discovered their former heroes from Georgia might just have been a self-serving cabal. The roots of the “Royal Party’s” demise, like the crisis itself, are tangled and deep but indisputably can be traced to the remarkable degree with which the small group of wealthy and politically connected Georgians guided Alabama through its territorial experience. They held leadership positions in its legislature and its financial institutions, and when the financial storm struck, they came under brutal scrutiny.

That many of them were associated with the embattled Planters and Merchants Bank would come to hang, albatross- like, around their collective necks as the depression dismantled homesteads the next year. Under the heat of the spotlight steadily applied by resentful antagonists, even former steadfast allies such as planter and financier Israel Pickens would separate from the Georgians. Running as “champions of the people,” these defectors soon banded together to claim more than their fair share of important offices. The panic did not end the days of the “Royal Party” power brokers in Alabama politics, but it marked the beginning of its demise.

The panic’s repercussions extended far beyond the purely economic realm in Alabama. In some ways it redefined the political landscape, since in finding a scapegoat for the calamity Alabamians believed they discovered their former heroes from Georgia might just have been a self-serving cabal. The roots of the “Royal Party’s” demise, like the crisis itself, are tangled and deep but indisputably can be traced to the remarkable degree with which the small group of wealthy and politically connected Georgians guided Alabama through its territorial experience. They held leadership positions in its legislature and its financial institutions, and when the financial storm struck, they came under brutal scrutiny.

That many of them were associated with the embattled Planters and Merchants Bank would come to hang, albatross- like, around their collective necks as the depression dismantled homesteads the next year. Under the heat of the spotlight steadily applied by resentful antagonists, even former steadfast allies such as planter and financier Israel Pickens would separate from the Georgians. Running as “champions of the people,” these defectors soon banded together to claim more than their fair share of important offices. The panic did not end the days of the “Royal Party” power brokers in Alabama politics, but it marked the beginning of its demise.

The panic did not end the days of the “Royal Party” power brokers in Alabama politics, but it marked the beginning of its demise.

While still in the throes of economic setbacks and the beginning stages of its first true political rivalry, cruel reminders that the territory could be a harsh place to make a living seemed to abound with an unprecedented vigor in 1819. On July 27, an intense hurricane slammed into Mobile, leaving a swath of destruction all along the Mississippi and Alabama coasts. Alligators and boats floated through the streets, and innumerable felled trees blocked roads throughout the region. “The whole coast from Rigolets to Mobile,” reported the New Orleans Courier, was “a scene of desolation, covered with fragments of vessels and houses, the bodies of human beings, and the carcasses of cattle.” That same month a particularly insidious outbreak of dreaded yellow fever struck Mobile as well, bringing business to a standstill. Commonly known at the time as “yellow jack,” the fever is a viral disease spread by mosquitoes. After a short incubation period, it manifests itself in a variety of unpleasant ways, including fever, headache, nausea, muscle pains, and the tell-tale yellowish tint to the skin caused by liver damage. Many of those who contracted the illness died within a matter of days—sometimes even hours. Fully half of Mobile’s residents are believed to have fled the area, and hundreds of those who remained died.

Yet even as such disasters ravished the territory, momentum continued to carry it towards its statehood destiny. Early in 1819 in the nation’s capital, a petition to Congress requesting immediate statehood, sent during the previous legislative session, had come up for discussion. Citing the “unparalleled tide of emigration, invited by the general fertility of our soil and the happy temperature of our Climate… daily flowing into the bosom of our Territory,” author John W. Walker insisted that its citizens “cannot conceive, how it could promote the interest of the national government, longer, to withhold from the people of Alabama the right they solicit.” He also reminded Congress that, with a population of nearly 70,000 people, the Alabama Territory easily surpassed the population of the recently admitted state of Mississippi and compared favorably to Indiana and Illinois, which entered the Union in 1816 and 1818, respectively. Sen. Charles Tait, close friend of many in the tight-knit Georgia Faction and soon to be resident of Alabama himself, guided the bill through Congress. On March 2, Pres. James Monroe signed the act that led to the state of Alabama. The act set forth the steps that needed to be taken for the new state to be admitted into the Union, including writing a constitution and establishing a government, and specified that elections be held in May to choose delegates to a July constitutional convention. Ironically, within a year that highlighted all that could go wrong on the frontier, Alabama finally prepared to make the transition that would mark the beginning of a bright new chapter in its story.

Yet even as such disasters ravished the territory, momentum continued to carry it towards its statehood destiny. Early in 1819 in the nation’s capital, a petition to Congress requesting immediate statehood, sent during the previous legislative session, had come up for discussion. Citing the “unparalleled tide of emigration, invited by the general fertility of our soil and the happy temperature of our Climate… daily flowing into the bosom of our Territory,” author John W. Walker insisted that its citizens “cannot conceive, how it could promote the interest of the national government, longer, to withhold from the people of Alabama the right they solicit.” He also reminded Congress that, with a population of nearly 70,000 people, the Alabama Territory easily surpassed the population of the recently admitted state of Mississippi and compared favorably to Indiana and Illinois, which entered the Union in 1816 and 1818, respectively. Sen. Charles Tait, close friend of many in the tight-knit Georgia Faction and soon to be resident of Alabama himself, guided the bill through Congress. On March 2, Pres. James Monroe signed the act that led to the state of Alabama. The act set forth the steps that needed to be taken for the new state to be admitted into the Union, including writing a constitution and establishing a government, and specified that elections be held in May to choose delegates to a July constitutional convention. Ironically, within a year that highlighted all that could go wrong on the frontier, Alabama finally prepared to make the transition that would mark the beginning of a bright new chapter in its story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed