Jeanne Elisabeth Helene Lajonie, known as Ninon, was born in Demopo-lis July 31, 1820, and she died in Gensac, Gironde, France, in 1911. Hers was probably one of the first births to the French emigres of the Vine and Olive Colony.

Jeanne Elisabeth Helene Lajonie, known as Ninon, was born in Demopo-lis July 31, 1820, and she died in Gensac, Gironde, France, in 1911. Hers was probably one of the first births to the French emigres of the Vine and Olive Colony. [Nicole Sauvage]

It is mistakenly believed that the Vine and Olive Colony was populated by wealthy aristocrats who wanted to craft a paradise out of the southern wilderness. The only notable person involved with the colony was General Count Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes. The aristocrat climbed up the ranks of the French Revolutionary army and received his title from Napoleon in 1808. Several other Napoleonic officers also arrived in Alabama but only for brief periods; Lefebvre-Desnouettes eventually left the state in 1821 to return to France, drowning off of the coast of Ireland. By 1830 the colony was depleted of its Napoleonic settlers, but this did nothing to stop romantic stories about the Vine and Olive Colony from remaining a part of the cultural history of our state.

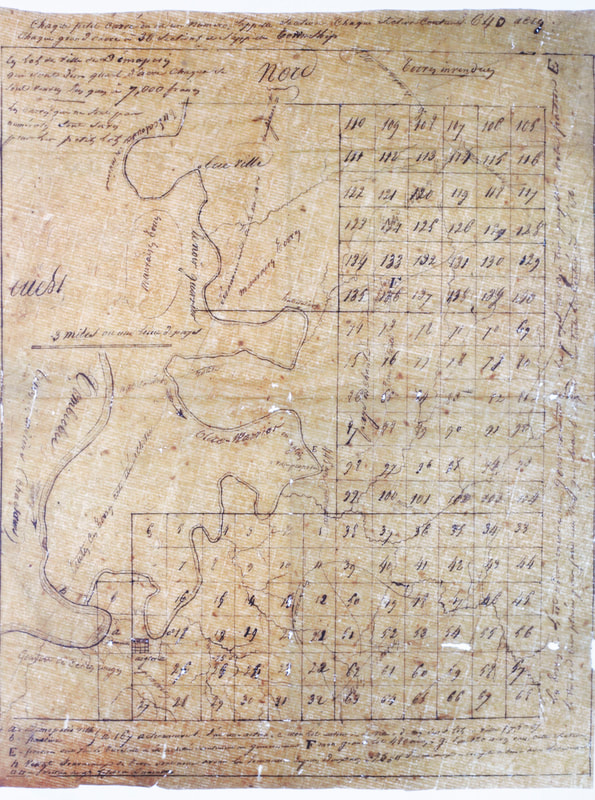

It was in Philadelphia that the "Society for the Cultivation of the Vine and Olive" was formed as a potential settlement for French settlers. In January 1817 the society decided upon a location for the settlement in territory that General Andrew Jackson took from the Creek and Choctaw Indians on the banks of the Tombigbee River. The bill proposing the tract of land, then part of the Mississippi Territory, was signed into law by President Madison on his last day of office, on March 3, 1817. The society was given 92,000 acres and a fourteen-year period in which to make the colony a viable success by the cultivation of grapevines and olive trees.

The endeavor was met with doubt from the very beginning. Alabama newspapers such as the Huntsville Republican disapproved of the awarding of superb land to "a company of foreigners" and predicted that the experiment would end in failure. The plan went forward despite these protests, as the United States wanted to boost their economy and cement their hold on territories along the Gulf Coast, particularly after the War of 1812. The Vine and Olive Colony would contribute to these goals, along with establishing a presence at the juncture of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior rivers that ultimately flowed into the Mobile Bay. Yet another reason for the awarding of such a large tract of land to foreign persons was that the United States hoped to become more self-sufficient in wine production.

The first settlers sailed from Philadelphia to Mobile and arrived in Marengo County in spring 1817; a much larger party of settlers arrived in August. The negotiation and sale of the territory's land tracts fell to General Charles Lallemand, who had served Napoleon and was now gathering funds to invade Texas, which was currently being fought over by Spain and the United States. This plan proved successful as more than eleven thousand acres were sold to St. Domingan merchants, and General Lallemand made the money he needed for his military expedition, which proved unsuccessful.

The settlers who continued to try to make the colony a success were French officers who had not sold their shares to General Lallemand; immigrants, banished exiles from France, and refugees from St. Dominique. They hoped to recreate the leisure they had enjoyed in the Caribbean, and this would have been impossible without implementing slavery in the colony. A Madame Victoire George quickly purchased a slave woman after arriving in Mobile and said that "We must absolutely have Negroes to cultivate our land." The purchase of slaves was a debilitating cost for the settlers, but most tried their best to acquire them, deplorably introducing slavery into that part of Alabama.

Food had to be imported to the colony at great expense and initially more corn and cotton was planted than grapevines. The log cabins the settlers constructed were not well-built and usually tiny; the largest measuring only nineteen by twenty-three feet, and offered little protection from the elements, including snakes, wolves, and bears. The city of Demopolis was founded by an earlier party of settlers but due to a surveying error, the city was actually outside of the colony's boundaries. Due to this the French settlers had to leave Demopolis and establish a new city further inland. They called it Aigleville (Eagle City), but it did not last.

When the settlers began seriously attempting the cultivation of vines and olives, their efforts were doomed from the beginning, as many of the plants died en route to the settlement or died after being planted, as they were unsuited to our state's climate. As late as 1831 attempts at viticulture were still attempted, but the only crop that was successful was cotton. The remaining settlers appealed to Congress to extend the years allotted to the grant and lower the prices to purchase further land, and this was granted. However, Congress never again granted immigrants a tract of land in which to begin a colony.

By the 1830s, the great French experiment was largely at an end. There were very few of the original 347 settlers left, and instead of vines there were fields of cotton. Most of the immigrants left for Mobile and New Orleans or returned to Philadelphia or France. The few French who remained were those rich enough to purchase slaves and begin plantations. An unusual blend of French culture and southern planters did remain in the area and the story of the Vine and Olive Colony settlers remains a part of Marengo County's heritage. The city of Greensboro has what is known locally as the “Vine and Olive house,” or more properly the Noel-Ramsey House, which is owned by the local historical society. It was built by a Vine and Olive colonist and features artifacts from that family. The story (very loosely) inspired a John Wayne film, The Fighting Kentuckian. Very few papers and artifacts of the settlers survive, but the legend lives on.

Sources

About the Author

RSS Feed

RSS Feed