Although it had been seven years since the British liner Titanic had struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic, losing fifteen hundred passengers at sea, people still remembered the disaster vividly. But all that seemed far away on this beautiful Sunday morning. Children in Tuscaloosa and the surrounding towns had been looking forward all week to Sunday afternoon, when Mr. S. F. Alston, a prominent Tuscaloosa banker and businessman, promised them a free holiday excursion on the Black Warrior River aboard his forty-foot yacht, the Mary Frances.

No one doubted that Sam Alston loved children. They "amused him," one contemporary wrote. "He was fond of their merry life, their wonderment, frankness, shrewdness and merry salutes." One of the first people in Alabama to own an automobile, he frequently filled it with children. In 1915 he purchased a yacht, which he named for his two granddaughters, Mary and Frances Rudulph, the children of his daughter Marilou. It surprised no one in town when he began offering trips on his new boat to local children.

The Mary Frances, according to reports, was a Peerless class launch built at Racine, Wisconsin, by the Racine Boat Company. A raised deck cruiser, forty feet long, with a beam of nine and a half feet, the vessel had a seating capacity of thirty-five and a berth capacity of eight. She was equipped with a full kitchen, running water, electricity, copper screening, and nickel finishings. For passenger safety, she carried a motor lifeboat. Her fifty-horsepower, self-starting engine furnished a top speed of twelve miles per hour.

Alston's Sunday afternoon excursions ran between Riverview, a point about halfway between Tuscaloosa and the Holt Lock and Dam, and the North River. A boating publication of the time referred to the Mary Frances as the "Boat Load of Happiness" for the pleasure she gave to area children, and recalled an August 1916 jaunt in which Alston entertained a total of 362 children aboard the vessel. The next year, he hosted employees of the Alston Lumber Company on a trip to Lock 17, and in 1918 he ran free excursions for soldiers training at the university, "carrying up to sixty at a time."

The yacht's trusted captain on all of these jaunts was Richard Antoni, known to all as "Captain Tony."

No one doubted that Sam Alston loved children. They "amused him," one contemporary wrote. "He was fond of their merry life, their wonderment, frankness, shrewdness and merry salutes."

The morning wore on slowly for children all over town, as they eagerly awaited the afternoon's excursion. Tuscaloosa postmaster Sam Clabaugh Sr., arranged with his father, J.H. Clabaugh, to accompany his son, Sam Jr., age five, on the boat ride. Sam's parents and little sister, Mary Oliver, stayed at home. Across town, two of Sam's playmates, James Cleere, six, and James Weir, eight, talked happily about the trip ahead. Mrs. Luther McGee and her young daughter traveled with a friend, Ruth Tucker, who came all the way from Coker to Tuscaloosa for the excursion.

Finally, it was time for the short trolley ride to Riverview, where the Mary Frances waited in dock. Tunstall "Tonsie" and Louise Robertson, ages seven and five, whose father ran the swimming pool at Riverview, excitedly left their home on Tenth Street to join the crowd. Mrs. L. Rosenfeld with her brood--Hyman, Dickie, Emanuel, and Louise--and Mrs. M.L. Waddell, with little six-year-old Elizabeth, joined the group at the dock, as did the four Bishop children and their mother.

A number of adolescent girls also showed up. Among them was Grace Lindsley, eleven, daughter of A.L. Lindsley, the lumberman, and Marguerite McGuire, thirteen, who had left her father, two little sisters, and a brother at home. Marguerite was excited about being out with her friends because only four months earlier her mother had died, leaving her to care for the three younger children. Other young people, some students at the University of Alabama, others at Tuscaloosa Female Institute, joined the group, as did several teenage boys from Kaulton and Northport and Coker.

Some who wanted to go missed the trip. When young William Collier, son of the society editor of the Tuscaloosa News, rushed to jump aboard, his brother James, standing on the bank, shouted, "You come back here, Bubber, don't get on that boat. There’s too many on there!" William turned and hesitated, and in a split second, the gangplank pulled up, leaving him standing on the dock. Miss Ruth Tinsley had also planned to go, but the boat had left by the time she arrived. Later it was said tl1at a certain young girl in Tuscaloosa had also planned on going, but she had disobeyed her mother the previous week. To teach her daughter a lesson, the mother kept her home that Sunday afternoon.

Despite assertions by some survivors that the boat was dangerously overcrowded, or that the turnaround was “too fast and too sharp,” only one lawsuit was ever filed in the case—a $50,000 claim, which was thrown out by the judge.

Only a quarter-mile up the river, the vessel neared the turn in the river at Holt, and Captain Tony called to the crowd, "I'm going to make a turn here. Everybody hold on, and if you haven't got anybody to hold on to, hold on to yourself!" With the boat at midstream, about one hundred yards from the bank, the captain made an acute left turn. Suddenly, the scores of passengers holding onto the rail felt the boat lean sharply, then the rail sank into the water and the boat capsized. Some of the passengers slid into the water; others were caught underneath the craft; still others were trapped below deck. People floundered, struggling to keep afloat, grasping for the few life preservers that floated on the surface. Echoes of screams and cries for help rang across the water's surface. Near the shore, a group of boys swimming beard the cries for help and swam quickly to assist tl1ose who were clinging to the hull of the craft.

Allen Parker Mize, Jr., of West End had been sitting on the port side of the upper deck when the captain announced he was going to turn. The next thing Mize knew, he was in the water. "I grabbed a life preserver that floated by, got it by one end, and a great big boy got the other end. Then a little girl floated by another life preserver and he did not seem to know what to do. So I got one end of her preserver and held onto one end of mine, and this big boy, the other, and we kicked and paddled and drifted into shore. The current took us a good ways down.

Mrs. Robert Cleere, her boy James, and his inseparable playmate, James Weir, had been standing on the top deck when the boat overtumed. Accordmg to accounts, "When Captain Antoni sang out about making the turn, both the little fellows, sitting side by side, grasped the same stanchion for support. As the boat careened over, Mrs. Cleere was thrown far from them and went down almost to the bottom, swallowing a great deal of water. She came to the surface, choking and strangling, and the only thing she could grasp was the almost red-hot exhaust pipe of the motor." Despite the heat, "she held on and looked for the two little boys--who were nowhere to be seen. They had held on so tightly they were carried down in the debris."

Down below, water rushed into the cabin. Eleven-year- old Grace Lindsley and the other children below deck scrambled to reach a high spot out of the reach of the rising flood.

“There was not many in the cabin,” explained Grace the next day. “The first thing I heard was when the little Robertson girls, Cleo, jumped out and her sister was hollering for help. And when the boat turned completely over, it was dark. There were only a few of us left—me and Marguerite McGuire and the two little Bishop boys. And then the water came over their heads, and they were drowned. I climbed up on a cracker box or something, and this just lifted my mouth and nose above the water, and I managed to get hold of two pipes or something to hold onto, and I stood that way.

“It was very dark, and the water was right along my chin. It was awful dark, and it was a long time. I talked to Marguerite McGuire until they started dragging the boat out, and then she went under and was drowned.

“A man reached through the hole and held me. I was hollering for my daddy when I heard them begin to hammer on the boat and cut a hole. My arms, which were bare, were scratched some when they pulled me out, but otherwise I was not hurt and feel all right this morning."

Just before the yacht gained water and began to sink, a group of teenage boys dove off the deck and swam to the bank. One of the Northport boys grabbed a life preserver and dragged a little girl to shore. The Kaulton boys, Roy Speed and his brother Stephen, both excellent swimmers, reached shore and were saved. Truman Waldron swam ashore holding a girl on a life preserver. Troy Wall also saved a little girl, but as Bill Wilson swam, he was pulled down twice by a little girl who clutched him about the neck. In her frantic efforts and terror, she came near taking both of them to the bottom of the Warrior. Bill recalled later that the girl was crying, "Save me, save me, and I'll be your sweetheart for life!" At that moment a rescue boat came up and took the girl to safety. Bill hung onto the overturned hull and waited till he himself was rescued. However, the two Albright boys drowned trying to escape.

Sadie Foster, Bettie Hood, Cecile Cunningham, and several other girls were standing on deck when the vessel began to sink. Sadie, a good swimmer, grabbed Bettie and held her head above\·e the water until a skiff picked them up. While Sadie was trying to balance, she felt someone pulling at her foot and was able to grab another child. Cecile Cunningham was pulled under four times by drowning children, but managed not to become strangled and was saved.

Lee McGee, eighteen, of Coker, who had come on board with his mother and little sister, was on the upper deck when the accident occurred. His mother and sister were on the lower. "I jumped just as the boat went over,'' said McGee later. "I grabbed a little girl and swam with her to the shore. I thought I had my sister, but could not look to see until I arrived at the bank. There was no warning of any sort of impending wreck--a sharp swerve of the boat, and suddenly it was on us. ... I'm glad I saved the little girl--I don't know who she is. But my little sister and my mother are dead."

Little Sam Clabaugh's grandfarher, J.H. Clabaugh, was flung into the water when the vessel capsized. He grabbed the boy, but the child was struck from his arms by a section of the boat. Polly Jones, with the help of her friends, Jerome Kennedy and Myrtie Burchfield, helped the old gentleman to shore, but in the wreckage and confusion, five-year-old Sam was lost.

The Northport boys, Howard Maxwell, Patton Evans, and Harris Strong, narrowly escaped drowning by swimming from the sinking boat; they then assisted other rescuers in pulling children from the river. Harris, though not an expert swimmer himself, threw his life preserver to a little girl who was saved.

Sam Alston was also thrown into the water, but managed to pull himself out by grasping the exhaust pipe with one finger. With his free hand, he grabbed as many children as he could. When a rescue boat arrived to pull them to safety, three children were clinging to his arm. Alston did not leave the scene, however, and stayed on the bank attempting to rescue victims until he was forcibly taken away at a late hour in serious condition. Captain Antoni struggled up the riverbank, exhausted and wild with grief. Observers said he seemed utterly bereft of reason and kept exclaiming over and over, ''Will the people of Tuscaloosa ever forgive me?" He was sedated and put under the care of a doctor and a Catholic priest, Father Lennehan.

Young Charles Rice, a carrier with the Tuscaloosa News, was the first to sound the rescue alarm. He had been standing at the stern when the boat turned over. An excellent swimmer, he dove into the water and was the first to reach the shore. Racing to the car barn at nearby Holt, he gave the alarm, and then caught the six o'clock car back to Riverview. There, on the bank, were relatives of the passengers, awaiting the return of the boat. None of them knew what had happened. When Rice told them, volunteers rushed immediately to the scene to help rescue victims.

A news story in the Tuscaloosa News later described the rescue attempt when people on shore learned of the disaster:

All work at the Semet-Solvay Company’s plant was immediately stopped, and all facilities of the company were turned toward assistance in rescuing the bodies. A huge hoisting engine was rushed down to the switch near the scene of the tragedy and cables attached to the overtumed craft, and it was in this manner hauled up out of the water, with the aid of many willing hands pulling on cables attached to the other end of the vessel. Huge searchlights used in the yards of the company were hurried to the scene and attached to the current and arc lights hastily erected to aid the growing fleet of small boats trying to rescue bodies from the river.

"Every once and a while a still, silent form would be brought to the undertaking establishment, and the roll of the dead would be increased by one," the newspaper reported.

Eugene Beatty, an electrician with the Tuscaloosa Railway and Utilities Company, directed the rescue effort and supervised recovery of the bodies. As he reported later, when rescuers climbed upon the overturned hull, they could hear voices from the cabin below. They chopped a hole into the hull with axes but struck metal, and could not free the imprisoned children without cutting away several pipes. A man from Semet-Solvay rushed to get a hacksaw, and with it workers made a small hole in the rear of the hull, enabling them to pull Grace Lindsley from the wreckage. Two small boys from Holt were also pulled from the front part of the cabin.

As the cables moved the wrecked vessel, more bodies slipped from the deck-one was six-year-old Robert Cleere and the other seven-year-old "Tonsie" Robertson.

Throughout the night the search parties dragged the river for bodies, aided by powerful searchlights from the government vessel Clio. By midnight most of the relarives had left the scene, leaving only rescue workers and "a scattered throng of the morbidly curious" on the muddy banks of the river. Other boats and barges rendered assistance, and two divers from Mobile-Capt. Frank Nelson and R. Bertalsen-went to work at the scene of the accident. One was equipped with ca t-iron shoes, the other with lead soles; each had a rope tied securely to his waist and had an air tube attached to the diving helmet. The divers walked along the muddy bottom twenty-two feet below, signaling to the surface crew every half-hour when they needed to come up and cool off.

On June 18, the Tuscaloosa News announced that the last body had been found:

At 2:30 o 'clock this morning the pitiful little body of Elizabeth Waddell, the six-year-old child of Mrs. M.S. Waddell, was found floating on the surface of the water near where tje boat went down. The mother also met her death in the dreadful disaster of Sunday when S.F. Alston's motor boat "Mary Frances" turned turtle opposite Holt, and 24 people went to their death beneath the waters of the Warrior River.

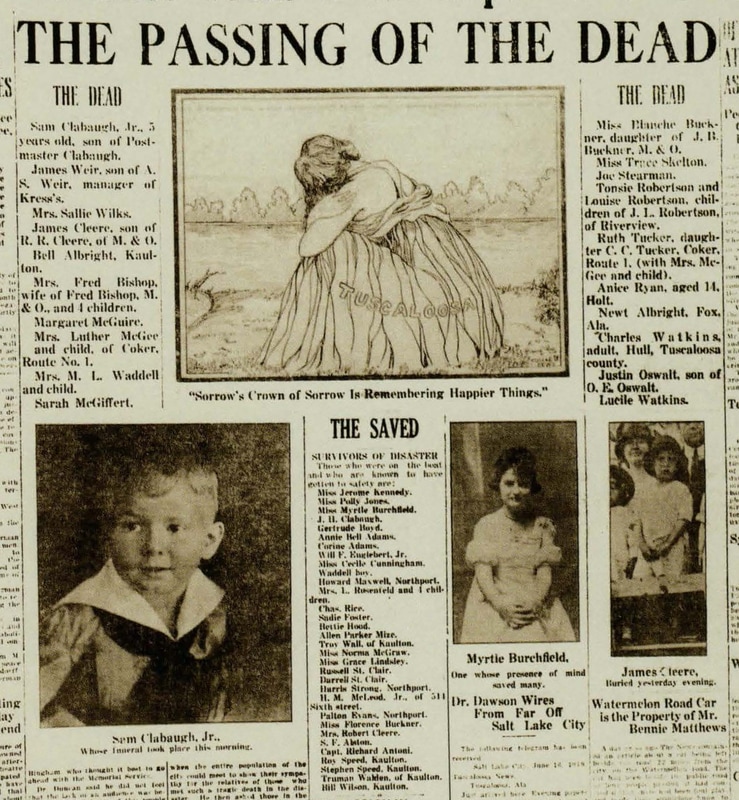

Almost immediately, the city began digging graves for the deceased. Sam Alston purchased grave plots in Evergreen Cemetery for all the victims and arranged to pay for their interment. The Tuscaloosa News reported that "Chief of Police McDuff took the street gang out to the cemetery this morning to dig graves, he not being able to do the work in the short time required." Funerals were arranged, some in the churches, some in the victims' homes. Obituaries and funeral notices filled column after column in Tuesday's and Wednesday's newspapers. A proclamation from the city commissioners appeared in Monday's paper, noting that the whole city was "inexpressibly shocked by the great calamity" and offering "heartfelt sympathy" to those who had lost loved ones. President of the Board of Commissioners D.B. Robertson called upon the community to close all businesses from noon to 2:00 p.m. on Tuesday, June 17. He also encouraged citizens to attend a memorial service in the Elks' Auditorium during that time "to give expression of their great sympathy for the families and friends who have suffered such overwhelming bereavement."

A newspaper editorial asked readers not to forget "the sympathy due the good citizen [Sam Alston], who tosses in delirium of mental agony over the tragic outcome of what he hoped would be only pleasure." The editors also extended condolences to the families involved: It is impossible to express in type the feeling of genuine grief and sorrow felt by the entire staff of the Tuscaloosa News. It has never been called upon to perform a more sorrowful office than carrying the news of this disaster, and may God in his mercy keep from us the task of ever having a similar duty to perform.

Other reports noted that Captain Antoni was in the depths of a "mental depression. ... The poor fellow went to the residence of Father Lennehan, where he lay on the floor for hours." When Sam Alston heard of the captain's state, he requested that Dr. Alston Fitts bring him to Alston's home, where Antoni was put under the care of a trained nurse. He was doing ''as well as could be expected,'' the paper noted, "for a man laboring under the great mental suffering he has undergone."

Another newspaper notice explained that "the seamstress shop of Mrs. G.C. O'Quinn did not close at 12 o'clock [on Tuesday], as other business houses did, on account of having to sew on the shrouds for the drowned, waiting to be dressed at the undertaking establishments."

A letter from inspectors appeared in Thursday's Tuscaloosa News, absolving Alston and Antoni from blame for the accident. Addressed to Alston and signed "very respectfully" by Henry O. Lueders and Harold F. Bean, U.S. Local Inspectors, the letter noted that "a careful and thorough examination" of the Mary Frances had been made. The inspectors found "the vessel to be a very substantial construction and according to all reports of the number of people carried on this trip, she was fully equipped with life-saving appliances and in our opinion, was in no wise overcrowded." The vessel turned over, in the inspectors' opinion, "through the shifting of the children and people carried from one side to the other for some unaccountable reason." The letter concluded by noting that the vessel had been "handled in a proper and seaman-like manner."

Other stories appeared in the paper that day clearing up misperceptions as to who had been on the boat that day. “Mr. Charles Watkins of Hulls was not drowned in the Mary Frances disaster, as has been stated. ... It now turns out that Mr. Watkins was not on the boat at all, and that it was his daughter, Louise, [who] was drowned and taken to Hulls for interment." Another story pointed out that a nurse, employed by the Bishops, had not been on the boat with Mrs. Bishop and her children, as some had thought. "It is remarkable," the paper noted, "that no more errors crept into the report than did, with all the confusion and excitement. The names of the victims, as far as possible to obtain them, were gathered on the banks of the river Sunday night, as the bodies were pulled from the hull of the boat, and as all was confusion, is there any wonder that there were not more errors?"

“Through whispered replies to my questions from aunts and our nursemaid, I learned that the small boy in the picture was ‘little Sam,’ and that he had drowned in a terrible accident.”

"I was only five when the Mary Frances capsized," Mary Burges Rudulph Steeves, the granddaughter of S.F. Alston, recalled recently, "but I sensed the grief and distress of my elders. I did not ask questions then or later as my mother grew sad at the mention. ... I like to think of the happy times aboard the Mary Frances. There were life belt drills when my grandfather gave a prize to the fastest. Noisy seagulls feasted on our breakfast scraps. Small islands of pretty, blooming water hyacinths floated by. Gentle water lapped against the sides of the boat."

Others have more painful memories.

"Mother never discouraged my lifelong love of water sports and boating--which, in retrospect, I find remarkable and for which I'm very grateful," says Betsy Plank Rosenfield of Chicago, whose mother, Bettie White Hood, had been saved from drowning by young Sadie Foster. "Mother never saved the press reports, never dramatized nor hugged the tragic experience. She spoke of it to me only once--mostly, I recall, about the blessing of a friend's courage and her abiding philosophy of 'what God has in mind.'

"Years later, she and my father, Richard J. Plank, flew to Chicago to join my husband and me in christening our first small boat. Afterwards, Dad came along for the maiden voyage on Lake Michigan; she stayed ashore and waited all afternoon. Never a word about why."

Jean Clabaugh Hiles, of Pensacola, recalls how the shock of losing her older brother, Sam, affected her family. "I have only the recall of a young girl wondering: Who is the little boy in the picture? If he is my brother, where is he? Why won't my parents tell me about him?

"Although my parents never talked to my sisters or me about our brother, I could sense something was very wrong. Through whispered replies to my questions from aunts and our nursemaid, I learned that the small boy in the picture was 'little Sam,' and that he had drowned in a terrible accident. I was admonished not to upset my parents with questions about him because it hurt them too much to talk about him.

"As I grew older, I realized that my mother and father never got over the loss, but they were determined that their sadness would not affect or hurt their four little girls. They were also determined that we would learn to swim at a very early age.''

Hiles also remembers another poignant incident when she was sixteen and a senior at Gulf Park High School on the Mississippi Coast. Several students and their fathers went out on an all-clay fishing trip aboard a small charter vessel.

"Daddy kept telling me, 'Be careful. Don't go over there. Watch out! There are too many on that side.' Finally, I asked, 'What in the world is the matter with you? I can't catch fish sitting down in the middle of the boat!'

“He looked at me and said, 'Don't you see what the name of this boat is?' And I replied, 'Yeah, the Mary Frances--so what?' I can still remember the sad wistful look he had as he replied, 'The Mary Frances was the name of the boat that turned over in the Black Warrior River when little Sam was drowned.' I had not known the name of the boat. Seeing his face, I had to fight back tears the rest of the day.''

Mason Clark Cleere, also of Pensacola, remembers his mother telling him the story and learning for the first time that he had had an older brother named James. "As a small boy, I would say, 'Tell me about little James, Mama. Tell me about my brother.' Her story came through much sobbing and flowing of tears from both of us." Cleere tells of the graves of his brother James and his brother's best friend, James Weir, buried side by side in Evergreen Cemetery, boys ''who died together and remain together after death.

"Robert Cleere, our father, said to me, 'If ever I hear a boat whistle, I recall that night as the boat whistles announced the discovery of another body."'

Barges and tugboats still course up and down the Black Warrior River, carrying coal from the mines of north Alabama to the port of Mobile. Private pleasure boats dot the waters on the weekends and holidays, but Tuscaloosa and its surrounding communities have grown and changed. Gone are the days when a single citizen would invite the entire town on a Sunday afternoon excursion. Also gone are most of the people who remember those earlier times--when parents and children, dressed in their Sunday best, rode the trolley to Riverview for an outing on the river.

This feature was previously published in Issue #61, Summer 2001.

Author

Frances Tucker, a retired public relations and marketing director for the University of Alabama Museums, served seven years as editor of NatureSouth, a natural history magazine published by the Alabama Museum of Natural History. While researching this article, Tucker collaborated closely with Rufus Bealle, retired University of Alabama attorney, using personal accounts of the tragedy contained in letters to Bealle, written by relatives of the survivors. Much of the report was taken directly from news stories published in the Tuscaloosa News during the week June 15-18, 1919. Special thanks go to Mary Burges Rudulph Steeves, Jean Clabaugh Hiles, Mason Clark Cleere, and Betsy Plank Rosenfield, all whom allowed the writer to use excerpts from their letters, and to the Cecile (Cunningham) Craig Foundation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed