Dedicated in 1910, Rickwood Field serves as the home of the Birmingham Barons of the Southern League and the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League.

Dedicated in 1910, Rickwood Field serves as the home of the Birmingham Barons of the Southern League and the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. (Photograph by Robin McDonald)

On August 18, 1910, Birmingham looked like a deserted city. All business had closed down, as had many stores in Bessemer and Ensley. It was "Baseball Day," and everyone in town who had the price of a ticket had gone to the grand opening of Rickwood Field. "There has never been such a day in Birmingham or in any other city of the Southern league," wrote one excited newspaper reporter. Sixty additional street cars had been put in service to aid in moving the anticipated crowd of as many as ten thousand people.

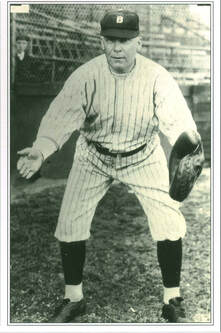

A. H. "Rick" Woodward, owner of both the Birmingham Barons and Rickwood Field, liked to dress in uniform and work out with the team.

A. H. "Rick" Woodward, owner of both the Birmingham Barons and Rickwood Field, liked to dress in uniform and work out with the team. Opening ceremonies at what the Birmingham Age-Herald called "the finest baseball plant in minor leaguedom" were formal but simple. After brief remarks by local officials, Judge William H. Kavanaugh, president of the baseball league, christened the new field by pouring champagne from a silver cup on home plate.

Then A. H. "Rick" Woodward–owner of both the Birmingham Barons and the new ballpark–threw out the first pitch. Woodward's toss, however, was not ceremonial. He had dressed out with the players and inserted himself on the roster in order to throw the game's first official pitch–"ball one," as it turned out.

Since that day in 1910, the ballpark has hosted many of the twentieth century's greatest players–Babe Ruth, Dizzy Dean, Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron, to name only a few and earned its place in history in other ways as well. In 1991, when Chicago's Comiskey Park was torn down, Rickwood Field became the oldest standing baseball stadium in the United States.

Baseball was already a firmly established part of Birmingham when Rick Woodward, son of millionaire industrialist Joseph Woodward, bought the Birmingham Coal Barons in 1909. The games were then played at the "Old Slag Pile" in West End, which had opened in 1901, but when Woodward purchased the Barons, he "fell heir to exactly nothing" in the way of a ballpark, he said. "The Old Slag Pile grandstand held about 600 people and was leased sixty days at a time." The new stadium would cost $75,000 and feature a concrete and steel grandstand, but it would not be completed until midway through the 1910 season.

Spring practice went well for the Barons that year, and Woodward was optimistic about their prospects. But three weeks into the season, with the Barons languishing in seventh place, he headed to Cincinnati in search of talent. There he bought Harry Coveleskie, paying one thousand dollars for him, and then went to Chicago, where he bought Bob Messenger from Charles Comiskey for another thousand. "It seemed to me that I had spent a fortune for ball players," he said later, "because in those days attendance was decidedly limited."

By late summer the Barons had rebounded, and on opening day at Rickwood Field, Harry "Big Pole" Coveleskie was on the mound. The Barons bunted their way to a 3-2 victory over Montgomery that night, while Coveleskie made the news for his "stirring mound duel" as well as for his "pugilistic stunts between innings."

Local press coverage of the opening ceremony was effusive. A reporter for the Birmingham Age-Herald wrote glowingly of the park, its owners, and the public spirit:

There is little doubt that the liberal efforts of "Rick" Woodward and other members of the association will redound to their benefit, for the modding populace of the Magic City entered into the spirit of the occasion yesterday and the spirit manifested by the 10,000 persons, and more, in attendance cannot and will not die.

This was language suited to a booming industrial town already captivated by the game of baseball.

Then A. H. "Rick" Woodward–owner of both the Birmingham Barons and the new ballpark–threw out the first pitch. Woodward's toss, however, was not ceremonial. He had dressed out with the players and inserted himself on the roster in order to throw the game's first official pitch–"ball one," as it turned out.

Since that day in 1910, the ballpark has hosted many of the twentieth century's greatest players–Babe Ruth, Dizzy Dean, Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron, to name only a few and earned its place in history in other ways as well. In 1991, when Chicago's Comiskey Park was torn down, Rickwood Field became the oldest standing baseball stadium in the United States.

Baseball was already a firmly established part of Birmingham when Rick Woodward, son of millionaire industrialist Joseph Woodward, bought the Birmingham Coal Barons in 1909. The games were then played at the "Old Slag Pile" in West End, which had opened in 1901, but when Woodward purchased the Barons, he "fell heir to exactly nothing" in the way of a ballpark, he said. "The Old Slag Pile grandstand held about 600 people and was leased sixty days at a time." The new stadium would cost $75,000 and feature a concrete and steel grandstand, but it would not be completed until midway through the 1910 season.

Spring practice went well for the Barons that year, and Woodward was optimistic about their prospects. But three weeks into the season, with the Barons languishing in seventh place, he headed to Cincinnati in search of talent. There he bought Harry Coveleskie, paying one thousand dollars for him, and then went to Chicago, where he bought Bob Messenger from Charles Comiskey for another thousand. "It seemed to me that I had spent a fortune for ball players," he said later, "because in those days attendance was decidedly limited."

By late summer the Barons had rebounded, and on opening day at Rickwood Field, Harry "Big Pole" Coveleskie was on the mound. The Barons bunted their way to a 3-2 victory over Montgomery that night, while Coveleskie made the news for his "stirring mound duel" as well as for his "pugilistic stunts between innings."

Local press coverage of the opening ceremony was effusive. A reporter for the Birmingham Age-Herald wrote glowingly of the park, its owners, and the public spirit:

There is little doubt that the liberal efforts of "Rick" Woodward and other members of the association will redound to their benefit, for the modding populace of the Magic City entered into the spirit of the occasion yesterday and the spirit manifested by the 10,000 persons, and more, in attendance cannot and will not die.

This was language suited to a booming industrial town already captivated by the game of baseball.

Baseball fever had spread through the South in the years after the Civil War, but in cities like Birmingham, where industry reigned, it was particularly intense. Industrialization brought sweeping technological changes that altered the way life was lived. Entire communities formed around mines and mills and furnaces, their rhythms governed by the clock rather than the sun and seasons. Life revolved around the company, which tried to control all aspects of workers' lives–where they lived, where they shopped, where they played. To mitigate the effects of industrial work, often both arduous and regimented, industry instituted programs and activities that both improved morale and increased production. Recreation became as much a company-sponsored activity as a personal pursuit, and it was not long before virtually every industrial enterprise had a team of its own.

Industrial leagues cropped up across the state. In Birmingham the first league was formed in 1905 by the YMCA. On its board were some of the city's leading industrialists: Thomas Hillman, president of Alice Furnace; William Barclay, secretary/treasurer of Alabama Ironworks; James W Sloss, founder of the Sloss Furnace Company; and William T Underwood, financier and coal and furnace developer. By the time Rickwood Field opened in 1910, the industrial leagues were such a pool of baseball talent that not only Birmingham but the entire state had become a hot recruiting ground for the professional leagues.

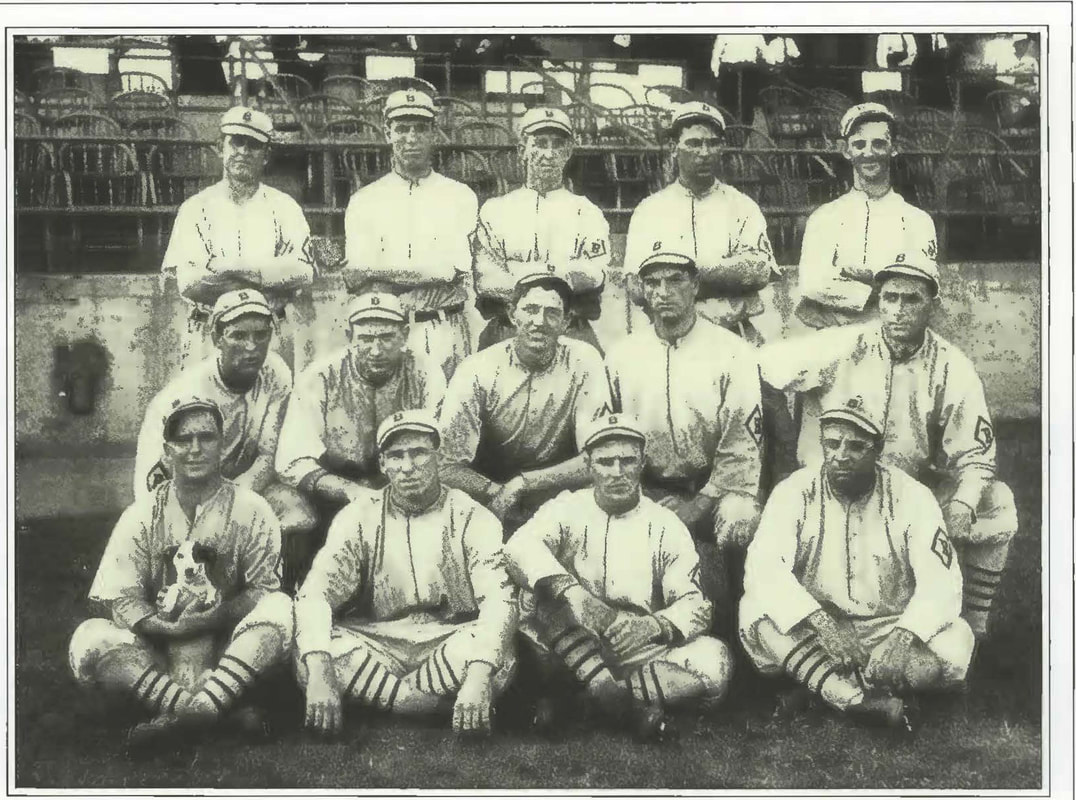

For the next fifty years, until television changed the game forever, Rickwood baseball was a source of civic pride. The Barons, perennial contenders for the Southern League pennant, won league championships in 1912, 1914, 1928, and 1931. Such early legends as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Lou Gehrig played exhibition games in Birmingham as they barnstormed across the country. In 1931 a young Houston Buffs pitcher named Dizzy Dean lost the first game of the Dixie Series to the Barons while more than twenty thousand ecstatic fans watched. The Barons won the series that year, fielding what Woodward called his best team ever. Baseball was the most popular sport in America, and although Birmingham was too small to support a major league franchise, it was brimming with baseball talent.

Rickwood Field was also home to the Birmingham Black Barons. Those were the days of Jim Crow, and black ballplayers, prohibited from playing on white teams, formed their own leagues. The Black Barons were organized in 1924, when members of the American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO) left the industrial league to form a team of their own. Other black players soon followed, some of them from the Stockham Valves and Fittings team. Segregation so limited economic opportunity in the black community that industrial league baseball was a serious business. Local industry recruited the best players for company teams, gave them jobs and often time off to play. If a black ballplayer didn't end up in the Negro leagues, he could still make a living playing for the company. Sometimes he could do both.

The Black Barons leased Rickwood from its owner and scheduled their home games on alternating weekends. The team was allowed to hire black concessionaires and park attendants but was restricted from using the locker-room facilities. Instead, players dressed in black-operated motels in the downtown area. Seating at Rickwood was segregated for all the Barons' games, black or white. About five hundred seats in the outfield bleachers were reserved for black fans during the Barons' games and for white fans when the Black Barons played.

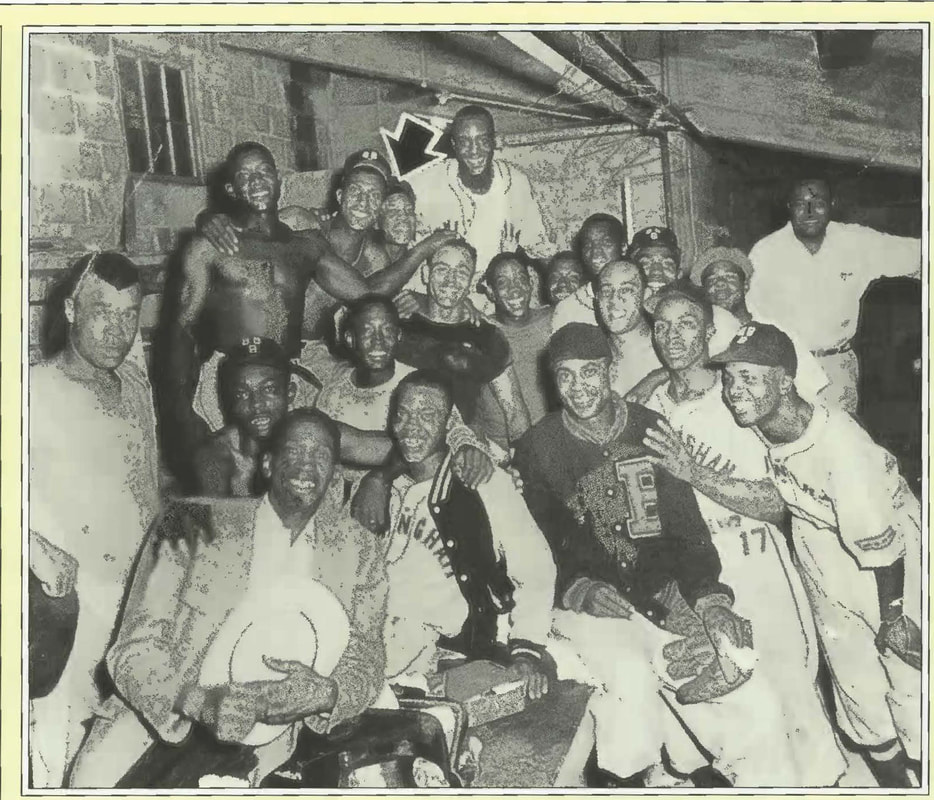

Just as the Negro leagues inspired a generation of black Americans, so the Black Barons sparked the imaginations of young people all over Alabama. Pitcher Satchel Paige came of age at Rickwood, going 23-15 in 1928 and 1929, with 184 strikeouts in 196 innings in 1929. This strikeout mark was a Negro league record that would never be matched. Another local hero was Birmingham native Piper Davis. For many years a standout second baseman for the Black Barons, Davis managed the 1948 championship team that saw a rookie from Fairfield named Willie Mays start in centerfield. In his memoirs, Mays called Piper Davis the most important person in his early baseball years. "Piper taught me many lessons. ... He told you something only once, and he expected you to go from there. That was a big reason why I matured so quickly. ... I learned fast in the Negro league and I learned hard, often right on the spot."

A common misunderstanding about the old Negro leagues is that they were minor league versions of white baseball. But as Mays pointed out, the best black ballplayers in the country played in the Negro leagues. "What kind of teams do you think were composed of the best black players in America?" he asked. "There have been a lot of myths about those times and leagues and players, as if we were just a bunch of characters flitting around in a sagging old yellow school bus, as if it was unorganized and sort of played just for fun, not following the rules. Nothing could be further from the truth."

The Black Barons won the Negro American League pennant three times in the 1940s and, with the Barons, ushered in the golden days of 1948. That year, both teams played to overflow crowds. The Barons set a Southern League attendance record, drawing more than 440,000 on their way to winning the Dixie Series behind future major leaguers Walt Dropo, Tommy O'Brien, and George Wilson. Meanwhile, the Black Barons were also packing the stadium week after week as they pursued the Negro American League championship. The team won the pennant but lost to the Homestead-Washington Grays in the Negro World Series. Several players from the 1948 Black Barons also went to the major leagues, once the color barrier was broken by Jackie Robinson: Willie Mays and Art Wilson to the New York Giants, Jehosie Heard to the Orioles, Bill Greason to St. Louis, Piper Davis to the Red Sox.

The stellar procession of ballplayers, both black and white, that moved through Rickwood Field came to a halt in 1962, when the Barons folded rather than integrate. For two years, Rickwood sat empty. When the Barons returned to play in 1964, it was with an integrated team. Desegregation essentially killed the Negro leagues, and beginning in the 1960s, stars like Reggie Jackson, Rollie Fingers, and Joe Rudi all wore the same Barons uniform.

The end for Rickwood came in 1987. Art Clarkson had bought the team in 1981 and spent seven hard years trying to make it at the old field. By then, however, the facilities had so deteriorated he was using a two-by-four to hold up the ceiling outside his office. When the opportunity arose, Clarkson moved the Barons south of the city to the new Hoover Met. "I remember every game for seven years," he told a Birmingham News reporter. "When we threw those lights on, we held our breath." The Barons left Rickwood in style, winning the Southern League pennant that same year.

Clarkson once called Rickwood the "bag lady of baseball." Over the years, the bag lady has weathered tornadoes and withstood leaking roofs and collapsing ceilings, flaking paint and power outages, and, more recently, graffiti. Now, finally, she has become the grand dame-the oldest standing baseball stadium in the U.S. Respected at last, she is earning the attention she deserves. In 1993 Rickwood was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and plans are underway to restore her former glory.

Industrial leagues cropped up across the state. In Birmingham the first league was formed in 1905 by the YMCA. On its board were some of the city's leading industrialists: Thomas Hillman, president of Alice Furnace; William Barclay, secretary/treasurer of Alabama Ironworks; James W Sloss, founder of the Sloss Furnace Company; and William T Underwood, financier and coal and furnace developer. By the time Rickwood Field opened in 1910, the industrial leagues were such a pool of baseball talent that not only Birmingham but the entire state had become a hot recruiting ground for the professional leagues.

For the next fifty years, until television changed the game forever, Rickwood baseball was a source of civic pride. The Barons, perennial contenders for the Southern League pennant, won league championships in 1912, 1914, 1928, and 1931. Such early legends as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Lou Gehrig played exhibition games in Birmingham as they barnstormed across the country. In 1931 a young Houston Buffs pitcher named Dizzy Dean lost the first game of the Dixie Series to the Barons while more than twenty thousand ecstatic fans watched. The Barons won the series that year, fielding what Woodward called his best team ever. Baseball was the most popular sport in America, and although Birmingham was too small to support a major league franchise, it was brimming with baseball talent.

Rickwood Field was also home to the Birmingham Black Barons. Those were the days of Jim Crow, and black ballplayers, prohibited from playing on white teams, formed their own leagues. The Black Barons were organized in 1924, when members of the American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO) left the industrial league to form a team of their own. Other black players soon followed, some of them from the Stockham Valves and Fittings team. Segregation so limited economic opportunity in the black community that industrial league baseball was a serious business. Local industry recruited the best players for company teams, gave them jobs and often time off to play. If a black ballplayer didn't end up in the Negro leagues, he could still make a living playing for the company. Sometimes he could do both.

The Black Barons leased Rickwood from its owner and scheduled their home games on alternating weekends. The team was allowed to hire black concessionaires and park attendants but was restricted from using the locker-room facilities. Instead, players dressed in black-operated motels in the downtown area. Seating at Rickwood was segregated for all the Barons' games, black or white. About five hundred seats in the outfield bleachers were reserved for black fans during the Barons' games and for white fans when the Black Barons played.

Just as the Negro leagues inspired a generation of black Americans, so the Black Barons sparked the imaginations of young people all over Alabama. Pitcher Satchel Paige came of age at Rickwood, going 23-15 in 1928 and 1929, with 184 strikeouts in 196 innings in 1929. This strikeout mark was a Negro league record that would never be matched. Another local hero was Birmingham native Piper Davis. For many years a standout second baseman for the Black Barons, Davis managed the 1948 championship team that saw a rookie from Fairfield named Willie Mays start in centerfield. In his memoirs, Mays called Piper Davis the most important person in his early baseball years. "Piper taught me many lessons. ... He told you something only once, and he expected you to go from there. That was a big reason why I matured so quickly. ... I learned fast in the Negro league and I learned hard, often right on the spot."

A common misunderstanding about the old Negro leagues is that they were minor league versions of white baseball. But as Mays pointed out, the best black ballplayers in the country played in the Negro leagues. "What kind of teams do you think were composed of the best black players in America?" he asked. "There have been a lot of myths about those times and leagues and players, as if we were just a bunch of characters flitting around in a sagging old yellow school bus, as if it was unorganized and sort of played just for fun, not following the rules. Nothing could be further from the truth."

The Black Barons won the Negro American League pennant three times in the 1940s and, with the Barons, ushered in the golden days of 1948. That year, both teams played to overflow crowds. The Barons set a Southern League attendance record, drawing more than 440,000 on their way to winning the Dixie Series behind future major leaguers Walt Dropo, Tommy O'Brien, and George Wilson. Meanwhile, the Black Barons were also packing the stadium week after week as they pursued the Negro American League championship. The team won the pennant but lost to the Homestead-Washington Grays in the Negro World Series. Several players from the 1948 Black Barons also went to the major leagues, once the color barrier was broken by Jackie Robinson: Willie Mays and Art Wilson to the New York Giants, Jehosie Heard to the Orioles, Bill Greason to St. Louis, Piper Davis to the Red Sox.

The stellar procession of ballplayers, both black and white, that moved through Rickwood Field came to a halt in 1962, when the Barons folded rather than integrate. For two years, Rickwood sat empty. When the Barons returned to play in 1964, it was with an integrated team. Desegregation essentially killed the Negro leagues, and beginning in the 1960s, stars like Reggie Jackson, Rollie Fingers, and Joe Rudi all wore the same Barons uniform.

The end for Rickwood came in 1987. Art Clarkson had bought the team in 1981 and spent seven hard years trying to make it at the old field. By then, however, the facilities had so deteriorated he was using a two-by-four to hold up the ceiling outside his office. When the opportunity arose, Clarkson moved the Barons south of the city to the new Hoover Met. "I remember every game for seven years," he told a Birmingham News reporter. "When we threw those lights on, we held our breath." The Barons left Rickwood in style, winning the Southern League pennant that same year.

Clarkson once called Rickwood the "bag lady of baseball." Over the years, the bag lady has weathered tornadoes and withstood leaking roofs and collapsing ceilings, flaking paint and power outages, and, more recently, graffiti. Now, finally, she has become the grand dame-the oldest standing baseball stadium in the U.S. Respected at last, she is earning the attention she deserves. In 1993 Rickwood was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and plans are underway to restore her former glory.

The Friends of Rickwood, a non-profit group formed in 1992, is leading the fund-raising effort, with help from the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce and other local organizations. About seven hundred thousand of the estimated seven million dollars needed for the project has been raised. The rest will come from a variety of sources--corporate sponsors, federal grants, and private contributions. The City of Birmingham has agreed to match all private donations.

Restoration plans, which will be phased in over a period of years, call for a new press box (to be built in fall 1995), the replacement of up to five thousand seats, rebuilding the outfield bleachers, landscaping and lighting the concourse and parking lot, new plumbing and electrical systems, and the construction of an almost three million-dollar museum dedicated to preserving the rich history of Rickwood Field and of Southern baseball in general.

Some of the restoration work has already begun. The dilapidated roof has been replaced, as have the wooden louvers Connie Mack designed to block the late afternoon Rickwood sun. Period billboards and a hand-operated scoreboard have also been installed.

As important as the physical restoration is the marketing plan. Since the departure of the Barons in 1987, the field has been used by Birmingham city school baseball teams and by the Board of Education, which has its athletics offices there. In January 1995, the Friends of Rickwood signed a fifty-year lease with the Birmingham Park and Recreation Board, giving the Friends exclusive authority to restore and manage the park. Headed by Terry Slaughter and Coke Matthews of Slaughter Hanson Advertising, the Friends group plans to market the facility as a site for major league exhibition games and high school and college baseball tournaments, as well as for movies and television commercials. But the group sees the facility primarily as a place to play baseball the "way it used to be played," and is especially interested in organizing and hosting turn-back-the-clock events. As restoration proceeds, the possibilities will only increase.

Baseball lore is not just about great legends. It's about the night Stuffy Stewart pulled the hidden ball trick for the eleventh time in the season, a league record. Or the time Barons pitcher Alvin Crowder bounced a ball off a batter's head and had it land on top of the grandstand. Or the game when Rowdy Elliott stepped to the plate with two out, three men on, and the Barons four runs behind, pointed to the centerfield stands, and knocked one over the fence, tying the game. Or the debate over who hit the longest home run–Walt Dropo? Hank Sauer? Piper Davis? It's about the stories that knit a community together with shared experiences to make a common culture. For nearly seventy years, Rickwood was one of the few places in Birmingham where all segments of society mingled, even if not always on the same day. If you want to trace the history of the city there, you can--look for the impact of industry, of segregation and desegregation, of suburban sprawl and urban decay), When asked about Rickwood and history and his commitment to the project, Coke Matthews replied, "Remember the Terminal Station [in downtown Birmingham] which was razed in 1969? I just don't want to be sitting around twenty years from now trying to describe how terrific Rickwood was and explaining why it was torn down. I hope the vintage photo of Rickwood on my wall always makes me smile with pride, knowing that the old place is alive and well, still telling stories and creating legends."

Restoration plans, which will be phased in over a period of years, call for a new press box (to be built in fall 1995), the replacement of up to five thousand seats, rebuilding the outfield bleachers, landscaping and lighting the concourse and parking lot, new plumbing and electrical systems, and the construction of an almost three million-dollar museum dedicated to preserving the rich history of Rickwood Field and of Southern baseball in general.

Some of the restoration work has already begun. The dilapidated roof has been replaced, as have the wooden louvers Connie Mack designed to block the late afternoon Rickwood sun. Period billboards and a hand-operated scoreboard have also been installed.

As important as the physical restoration is the marketing plan. Since the departure of the Barons in 1987, the field has been used by Birmingham city school baseball teams and by the Board of Education, which has its athletics offices there. In January 1995, the Friends of Rickwood signed a fifty-year lease with the Birmingham Park and Recreation Board, giving the Friends exclusive authority to restore and manage the park. Headed by Terry Slaughter and Coke Matthews of Slaughter Hanson Advertising, the Friends group plans to market the facility as a site for major league exhibition games and high school and college baseball tournaments, as well as for movies and television commercials. But the group sees the facility primarily as a place to play baseball the "way it used to be played," and is especially interested in organizing and hosting turn-back-the-clock events. As restoration proceeds, the possibilities will only increase.

Baseball lore is not just about great legends. It's about the night Stuffy Stewart pulled the hidden ball trick for the eleventh time in the season, a league record. Or the time Barons pitcher Alvin Crowder bounced a ball off a batter's head and had it land on top of the grandstand. Or the game when Rowdy Elliott stepped to the plate with two out, three men on, and the Barons four runs behind, pointed to the centerfield stands, and knocked one over the fence, tying the game. Or the debate over who hit the longest home run–Walt Dropo? Hank Sauer? Piper Davis? It's about the stories that knit a community together with shared experiences to make a common culture. For nearly seventy years, Rickwood was one of the few places in Birmingham where all segments of society mingled, even if not always on the same day. If you want to trace the history of the city there, you can--look for the impact of industry, of segregation and desegregation, of suburban sprawl and urban decay), When asked about Rickwood and history and his commitment to the project, Coke Matthews replied, "Remember the Terminal Station [in downtown Birmingham] which was razed in 1969? I just don't want to be sitting around twenty years from now trying to describe how terrific Rickwood was and explaining why it was torn down. I hope the vintage photo of Rickwood on my wall always makes me smile with pride, knowing that the old place is alive and well, still telling stories and creating legends."

This article was first featured in Alabama Heritage, Issue 38.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed