With a twenty-member volunteer board and part-time staff at the Alabama Historical Commission, the council has a solid track record of leadership and achievement. It has engaged people across the state in celebrating, appreciating, recording, registering, preserving, and reusing a wide range of African American historic places. An initial mailing list of under one hundred has grown to over eight hundred. In 1983 the Alabama Register and National Register included only forty-two places associated with African Americans. In 2009 the number had grown to 173. The council’s internship program is also increasingly popular. Two graduates are currently employed as professional preservationists. Many others have become committed preservationists.

The council holds annual community forums that tackle specific preservation issues, whether involving an old schoolhouse in a rural area like Calhoun County’s Choccolocco Valley or a neighborhood in a major urban area like Birmingham or Mobile. A 2001 forum in Birmingham highlighted churches in the city linked with the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Last year the gathering—in Hobson City, near Anniston—brought national press attention to preservation issues related to Alabama’s oldest African American incorporated community.

As almost every preservationist recognizes, when people know why places are important, they are more likely to want to keep them. Three of the council’s major public education campaigns brought needed attention to Alabama’s African American churches, its historically black colleges and universities, and the 1965 Voting Rights March Trail, a fifty-four-mile section of U.S. Highway 80 between Selma and Montgomery.

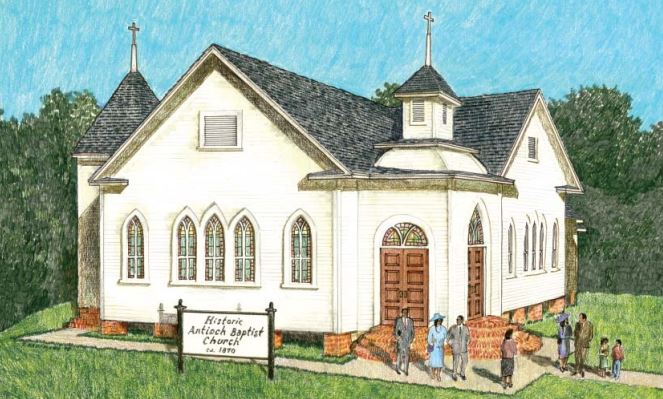

“Keepers of the Faith,” the council’s series of calendars, brought widespread attention to Alabama’s historic African American churches in 1989, 1990, and 1991. Next, it developed a poster profiling the state’s nine historically black colleges and universities, increasing awareness of the role these schools played in Alabama’s segregated world prior to the 1960s.

When a 1993 National Park Service study recommended that the Voting Rights March route be designated a national historic trail, the council went to work. It commissioned an interpretive study of the route and a traveling exhibit with a companion brochure. The exhibit is still available to nonprofit organizations for the cost of shipping. Today the route is designated an All-American Road, a National Scenic Byway, and a National Historic Trail with interpretative signs along the highway. The National Park Service operates a museum at White Hall, midway between Selma and Montgomery. “All across Alabama, we find African Americans who want to preserve the places that so vividly tell our stories,” says Chair Taylor. “Because of the council, these citizens are now plugged into a broader network of likeminded people.”

For more about the Black Heritage Council and its programs, see its website at

https://ahc.alabama.gov/blackheritagecouncil.aspx or call (334) 242-3184.

This feature was previously published in Issue 97, Summer 2010.

Authors

Frazine Taylor is chair of the Alabama Black Heritage Council and is retired from the staff of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. Dorothy Walker is outreach coordinator for the Alabama Historical Commission. Robert Gamble is senior architectural historian for the Alabama Historical Commission and is standing editor of the “Southern Architecture and Preservation” department of Alabama Heritage.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed