In spite of this inhospitable legal climate, a number of free blacks made reasonably good livings in antebellum Alabama. Most lived in cities where they worked in the trades-as carpenters, teamsters, blacksmiths, barbers, cooks, and cigar makers. Their contribution to the economic well-being of Southern society was not lost on many whites. Even the Alabama legislature, on occasion, passed laws freeing certain blacks and exempting them from the requirement that they leave the state. One such free black was Horace King, who began life as a slave, gained his freedom, and managed to forge a singular path through the minefield of antebellum Southern society to become Alabama's foremost bridge builder and one of the South's most respected engineers.

Information on Horace King's early years is scanty. He was born a slave in the Chesterfield District of South Carolina on September 8, 1807. His father was a mulatto named Edmund King; his mother, Susan (or Lucky), was the daughter of a full-blooded Catawba Indian and a black female slave. In the winter of 1829, Horace King's master died, and King and his mother became the property of John Godwin, a South Carolina house builder and bridge contractor.

Information on Horace King's early years is scanty. In 1829, Horace King's master died, and he became the property of John Godwin, a South Carolina house builder and bridge contractor.

John Godwin was both. He was well versed in the bridge-building innovations of Connecticut architect Ithiel Town. It is possible that Godwin had even worked with Town himself beginning in 1822 when the architect came to supervise the construction of a bridge he had designed to span the Pee Dee River at Cheraw, South Carolina. Town's design, which he had patented in 1820 and called the "Town Lattice Truss" (page 38), was an entirely new system of wooden framework that could be erected using inexpensive common sawmill lumber and the labor of any carpenter's gang.

It is likely that Horace King also became acquainted with Town's innovative truss design at the Pee Dee River bridge site. Perhaps he helped construct the bridge. Perhaps it was here that he first became acquainted with Godwin. What is certain is that both Godwin and his servant King were familiar with the Town Lattice Truss before they left South Carolina for Columbus, Georgia, in 1832.

In the early 1830s, Columbus-located across the Chattahoochee River from what became Girard (settled in 1832; now a part of Phenix City), Alabama-was the largest of the few raw border towns scattered along the river. Until1832, the vast tract of land to the west of Columbus belonged to the Creek Indians. Encompassing what is today Barbour, Calhoun, Chambers, Coosa, Macon, Lee, Randolph, Russell, Talladega, and Tallapoosa counties, this land was ceded to Alabama by the Creeks at the Treaty of Cusseta, March 24, 1832, thus opening the way for further westward expansion of the United States.

Anticipating the rush of immigrants who would flock to the newly opened territory, one Georgia investor in 1831 established a ferry across the Chattahoochee one mile south of Columbus. To the investor's disappointment, however, Columbus developed to the north, not the south, and to make matters worse, city officials decided that their growing city needed a bridge, not a ferry, to connect Georgia and the newly opened territory in Alabama. Despite protests from the “south end,” the city fathers advertised for bids in the local paper.

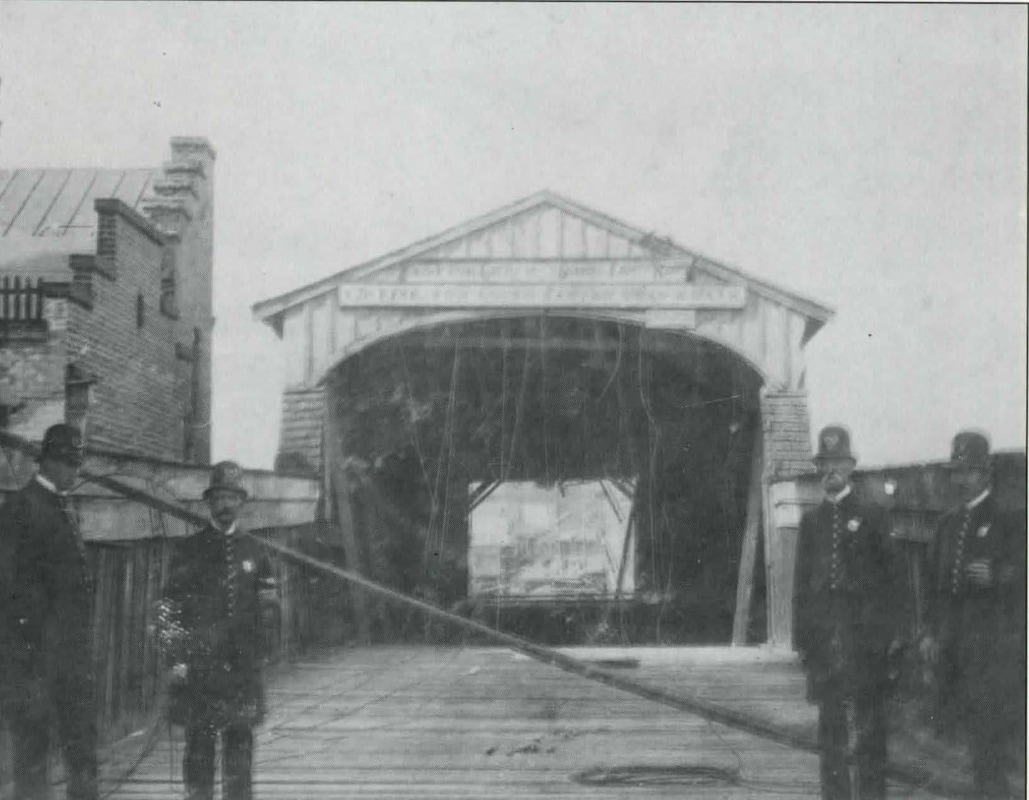

When the ad was brought to the attention of John Godwin, he quickly submitted a bid, which was accepted by city officials in March 1832. Thus, Godwin and his slave Horace moved to Columbus to construct the first public bridge over the Chattahoochee. The company, known as John Godwin, Bridge Builder, commenced work "with a large force" in May. In July they advertised in the Columbus Enquirer for "two or three Stone Masons, to work on the Piers of the Columbus Bridge, to whom liberal wages will be paid .... " In August the same paper noted with pride will add very much to the beauty and convenience of the town," was well underway. When completed, the 900-foot-long covered bridge, designed in the Town truss mode, earned Godwin and King reputations as master bridge builders

Apparently, from the beginning of their relationship, King was more of a junior partner in Godwin's company than a slave.

Because of the superior workmanship on the bridges King supervised, Godwin was able to guarantee his bridges for five years, even against floods. And when flood-related damage did occur, Godwin took full responsibility. The flood of February and March 1841, known as the "Harrison Freshet" (named for the ninth president of the United States, William Henry Harrison, who died of pneumonia in April· of that year), destroyed a portion of the bridge south of Columbus at Florence, Georgia, and swept away almost the entire City Bridge in Columbus. Godwin repaired both spans quickly. The Florence bridge was reopened to traffic by mid-April of that same year, and Godwin rebuilt the City Bridge within only five months. Horace King's skill and ingenuity made these feats possible.

In addition to building bridges, King probably also worked on the important houses that the Godwin firm built around Girard and Columbus during the 1830s and 1840s. Perhaps he supervised the slave workmen said to have remodeled U.S. Senator Seaborn Jones' home, "Eldorado." Certainly King worked for Jones, who hired him to build City Mills north of Fourteenth Street in Columbus. King also worked on the Muscogee County Courthouse (1838) in Columbus, and the Russell County Courthouse (1841) in Crawford, Alabama. And he continued to build bridges for Godwin.

King's precise contribution to the design modifications evident over the years in God win's bridges can only be speculated upon. The bridges King supervised contained additional intermediate chords, a feature that strengthened the trusses against twisting with age (Town himself had tried to correct this problem by doubling the number of web members). Some of King's bridges contained pier foundations formed by combining sand with timbers of heart pine. Also improved over time were the procedures King employed in erecting or assembling-without power machinery-vast trusses over water. Whether or not King was responsible for these innovations, he was certainly responsible for the care and efficiency with which these structures were erected. Indeed, King's ability to supervise massive construction projects and to elicit superior workmanship from mixed gangs of laborers, both slave and free, impressed some of the most successful businessmen in the South.

One of these men was Robert Jemison, Jr., of Tuscaloosa, a lawyer and state senator, a prosperous planter, and the owner of a large and well organized network of interrelated businesses, including a stagecoach line, a turnpike and bridge company, and extensive saw mill operations. In the early 1840s, Jemison began contracting with Godwin for bridges in west Alabama, coordinating the contracts so that his mills supplied lumber for the projects while Godwin furnished the carpenters. Horace King supervised construction. After several joint ventures with Godwin and King, Jemison wrote to Godwin in 1845: "Please to add another testimonial to the style and dispatch with which [Horace King] has done his work as well as the manner in which he has conducted himself."

King's ability to supervise massive construction projects and to elicit superior workmanship from mixed gangs of laborers, both slave and free, impressed some of the most successful businessmen in the South.

As King's fortunes rose, however, those of his master declined. By 1846 Godwin had suffered a series of financial setbacks. Realizing that King could be taken from him to settle debts with his creditors, Godwin arranged with Robert Jemison to petition the Alabama General Assembly for King's release from slavery. Jemison succeeded, and on February 3, 1846, Horace King became a free man.

The next decades were particularly productive for King. He built a bridge across the Flint River at Albany, Georgia, as well as a bridge house that functioned as a portal to the span. That project, completed in 1858, had been the special interest of Albany entrepreneur Nelson Tift, an energetic and inventive businessman interested in developing south Georgia's economic resources. Having failed to interest either the city or the county in his bridge-building idea, Tift decided to undertake the project himself. To oversee construction he hired Horace King. At the time, King was preparing to build a bridge over the Oconee River near Milledgeville. He had already cut timbers at the site when a disagreement over terms arose between King and his employers in the Milledgeville area. Unable to resolve the disagreement, King shipped the cut timbers by rail to Albany, thus becoming perhaps the first builder in the South to prefabricate a major structure and ship it to the construction site.

As a free man, King also continued to work with Jemison on a variety of projects. Jemison, a member of the state house ways and means committee, may have helped King secure work on the second Montgomery statehouse, constructed in 1850-51. Jemison and King bid on construction for Madison Hall, a dormitory at the University of Alabama, but did not get the bid. Jemison also consulted with King during one of the most massive construction projects undertaken in antebellum Alabama-the building of the Alabama Insane Hospital (Bryce) in Tuscaloosa, completed in 1860.

During the 1850s, John Godwin's fortunes continued to decline, primarily because of the failure of the Girard-Mobile Railroad in which Godwin had invested heavily. When Godwin died in 1859, his estate was insolvent, although the family still owned their large sawmill operation in Girard. The Godwin children, worried that King could be held accountable for their father's debts, took one further step to ensure his freedom by formally recording in the Russell County Courthouse that "the said Horace King is duly emancipated and freed from all claims held by us."

Even after John Godwin's death, King remained close to the Godwin family, helping Godwin's son run the failing family business. King publicly stated his affection for his former master on a large Masonic monument that he purchased for $600 and erected on Godwin's grave. The inscription reads:

John Godwin Born Oct. 17, 1798. Died Feb. 26, 1859. This stone was placed here by Horace King, in lasting remembrance of the love and gratitude he felt for his lost friend and former master.

King family recollections hold that at the time the Civil War broke out King and his son Marshall Ney were visiting friends in Ohio where King was inducted into the Masons, an affiliation that would prove useful after the fall of the Confederacy.

Soon after the hostilities began, King returned to the Chattahoochee Valley, apparently to manage the Godwin mill and contracting business for the Godwin family while John Godwin's son served as an artillery captain in the Confederate army. King also brought his other sons into the operation--John Thomas, Washington, and George.

The war years were difficult for King personally (his wife died in 1864) and professionally, as he tried to hold the Godwin family operation together and continue to work on his own. But construction jobs were plentiful. In 1863, James H. Warner, chief engineer for the Confederate navy, hired King (not the Godwin firm) to build a rolling mill for the Confederacy. Records from 1863 and 1864 show that King supplied logs, treenails (wooden pegs), large oak beams, oak knees, and 15,630 board feet of lumber for the construction of the Confederate ironclad gunboat Jackson.

King suffered the same vicissitudes as other Southern businessmen who worked for the Confederacy. Once, at the end of the war, Federal troops passing through Girard took two of his best mules. After considerable difficulty, King retrieved the mules, with apologies from the Union officers, after King proved to them that he was Mason. In some respects, he had less luck with the Confederate government, who paid him in currency that ultimately proved worthless. King's descendants kept the Confederate money until the 1920s, when they threw it out as "trash," and King himself never again accepted payment in any currency but silver coin.

After the war, King's fortunes rose again. His sons, and later, his daughter, joined him in business, forming the King Brothers Bridge Company, and together they rebuilt bridges, factories, and other structures that had been destroyed during the war. In 1865 they built a four-story wooden factory on the Chattahoochee about two miles north of Columbus for J. R. Clapp. In 1869 they rebuilt the City Mill in Columbus for Duer, Pridger, and Stapler (the tin-covered factory building still stands today), and in 1870, they completed a railroad bridge across the Chattahoochee for the Mobile and Girard Railroad, a project they had begun in 1860 but had to abandon.

Gradually, King began to turn the business over to his children, primarily to John Thomas who became head of the family in his father's declining years. In 1869, King, now age 62, married Sarah Jane McManus, about whom little is known except that she was thirty-five years her husband's junior. King also pursued interests outside the company. Urged by friends to seek public office, he allowed his name to be entered into the race for the Alabama House of Representatives. He won election twice, both times without actively campaigning, and served from 1868 to 1872. While in the legislature, King introduced several bills, one providing for "the relief of laborers and mechanics." Another required Russell County's commissioners to employ convicts sentenced to hard labor to work on "the public highways and public works of said county." He also served as a member of the standing committee on the capitol.

In addition to his legislative post, King served as magistrate for Russell County for a period after the war.

In the 1870s, the family moved from Alabama to LaGrange, Georgia. The reasons for the move are unclear. Perhaps John Thomas had decided that business prospects were better there. Or, perhaps the move had something to do with Horace King's interest in the work of the Freedmen's Bureau, the federal agency established to help safeguard blacks from any form of re-enslavement. Education for blacks had long been a concern of King and his eldest son, who believed in the old axiom, "Ignorance breeds poverty." Horace King hoped to establish a "small colony'' in Coweta or Carroll County, Georgia, where former slaves, both men and women, could study. It was not intended to be a utopian community, but simply a school designed to teach men trades and women "the domestic arts." Records indicate that the idea was blessed by Brigadier General Wager T. Swayne, assistant commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau for Alabama, and by his superior, Colonel C. C. Sibley, Assistant Commissioner, District of Georgia, but no records have been discovered that tell us whether or not the colony was established.

Throughout the 1870s, the King Brothers' construction firm continued to prosper, building a new chapel for the Southern Female College (1875-76) at LaGrange, Georgia; King himself laid the cornerstone and spoke from the platform at the accompanying ceremonies. They also built LaGrange Academy (c. 1875), that city's first black school, as well as the Warren Chapel Methodist Church and parsonage (c. 1875), also in LaGrange.

By the 1880s Horace King was enjoying a prosperous old age, comfortable in the home he had built for himself in LaGrange. Despite serious bouts with arthritis, King, a lifelong equestrian, spent his remaining years raising and riding fine horses. Occasionally he would stroll down the main street of town wearing a velvet lapel suit. One observer, the Rev. Francis LaFayette Cherry, described the elderly King in 1883 as displaying "wonderful vigor for his years. In person he is a little above medium size and height, with a complexion showing more his Indian blood than any other. His countenance is broad and open, eyes keen and black. ... His hair is nearly straight and almost as white as snow, and he wears a small tuft of grey beard under his lower lip. . . . He is never demonstrative, and is choice in the selection of words without appearing to be so."

When King died May 28, 1885, his body, according to family members, was carried "through the town and the men-and ladies too--came out of the shops and stores and stood with their arms folded over their hearts. . . . He was well-respected in that town."

Today King is remembered primarily for his bridges. He and John Godwin had been the first to span the Chattahoochee River, joining Georgia with the new frontier states to the west. Together they had helped to open up the region and blend the Chattahoochee Valley into a single industrial and cultural unit. None of King's major bridges stand today, but the Red Oak Creek Bridge, a small crossing attributed to King, still stands in Meriwether County, Georgia, kept in good repair through the efforts of the Meriwether County Historical Society. Still open to traffic almost a century and a half after its construction, this fine example of a Town Lattice Truss bridge remains a fitting monument to the man Robert Jemison, Jr., in 1854, called "the best practicing Bridge Builder in the South."

This feature was originally published in Issue #11, Winter 1989.

Author

Tom French, a registered landscape architect and land surveyor, and Larry French, an urban planner and historic preservationist, are a father and son team who work together as partners in the firm French & Associates, Columbus, Georgia. In the early 1970s, when Tom French was teaching a course in mechanical drawing at Pacelli High School in Columbus, he and his class became interested in covered bridges and decided to construct a model. From that beginning, French and his son developed a fascination for these nineteenth-century structures that led them on a four-state journey from the Chesterfield District of South Carolina through Georgia and Alabama to Lowndes County, Mississippi, in search of covered bridges, particularly those built by Horace King. Subsequently the Frenches have written a book on the subject, Covered Bridges of Georgia (The Frenco Company, Columbus, Georgia, 1984); they have also developed a slide show on Horace King, which they have presented to historical groups in Georgia and Alabama. The authors and the editors wish to thank William H. Green, Gary and Elizabeth Mills, Elise H. Stephens, Robert O. Mellown, and Robert S. Gamble for research assistance with this article.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed