Booker T. Washington’s increasing national prominence, gained in large part through his relationship with Pres. Th eodore Roosevelt, led to increasing attacks from the white southern establishment.

Booker T. Washington’s increasing national prominence, gained in large part through his relationship with Pres. Th eodore Roosevelt, led to increasing attacks from the white southern establishment. Washington believed that progress depended on racial reconciliation. He famously said that afternoon that “in all things that are purely social,” Blacks and whites “can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to human progress.” Economic goals must be put first, and therefore “the wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremist folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing.” The overarching message that Washington intended was Black progress, not acceptance of disfranchisement and segregation. African Americans were moving forward and upward. He challenged the presumption of the white South that in freedom African Americans had declined in character and morality. He insisted instead that Blacks were a people of “love and fidelity” to whites, a “faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful” people.

During the 1880s and early 1890s, Washington had made Tuskegee Institute an objective demonstration of Black progress. His effective fundraising enabled rapid growth of his school. By 1895 Tuskegee had more than six hundred students, far more than the number enrolled at the University of Alabama or at the Agricultural and Mechanical College at Auburn. Tuskegee was producing as many teachers as white schools in Alabama together.

His success came amid difficult personal struggles. Widowed twice during the 1880s—each wife had been a loving and capable helpmate in building the school—in 1893 he married Margaret Murray, whose more robust health enabled her to be Washington’s long-term partner in building the school and representing the African American race.

Tuskegee Institute was a striking physical achievement, eventually boasting thirty buildings sprawled up and down a series of low hills, many of them multistoried structures made from red bricks manufactured on the campus. The students put up buildings with materials purchased by captains of American industry—Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Collis P. Huntington. Beyond the center of campus sprawled almost two thousand acres of land devoted to vegetable growing, livestock husbandry, and cotton cultivation—much of it overseen by the brilliant but eccentric horticulturalist George Washington Carver.

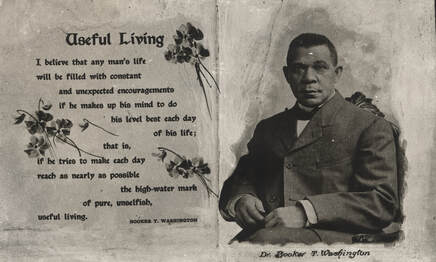

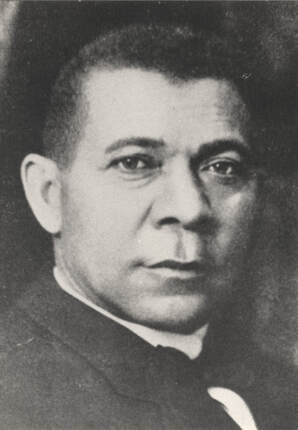

As he rose to national prominence by 1900, Washington’s abilities were widely appreciated. Perhaps no man in the United States had a better command of events and issues—certainly those that pertained to the South—than Washington. He read constantly, corresponded voluminously, and listened more intently to a wider variety of perspectives than the best journalists in America. The leading men in the country shared their thoughts with him, and three U.S. presidents sought his opinions. The richest men in America—Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Huntington—admired his ability, common with their own, to build a great enterprise and to integrate the aspirations of his beleaguered people into the booming American industrial economy. People all over the world read Washington’s 1901 autobiography Up from Slavery and took from it instruction and inspiration about how to improve their own lives. Washington personified the power of a person to educate himself.

Americans, Black and white, clamored to hear Washington’s inspirational and humorous speeches. Each year he spoke scores of times, all over the U.S., often to thousands of people at a time, about how African Americans could and would rise in American society and how relations between Blacks and whites were becoming more peaceful. Whites who went skeptically to hear the famous “Negro” often left persuaded by his message of hope. His prophecies about a better future for his race won him wide popularity among Blacks. Each year hundreds of African American mothers named their boy babies “Booker T.”

Washington’s audiences remembered his sayings. “I would permit no man to drag down my soul by making me hate him,” he told Blacks, and then to whites: “One man can’t keep another man in the ditch without being in the ditch himself.” He often cast his materialist emphasis in the statement, “No one cares much for a man with an empty hand, pocket and head, no matter what his color is.”

Washington deployed racial humor that often was ironic criticism of whites. On the social conditions in the South: “The colored men down South are very fond of an old song entitled ‘Give me Jesus and you take all the rest.’ The white man has taken him at his word.” He told the story of a white man who asked a Black fellow to loan him three cents to take a ferry to cross a river, but the Black man refused, saying, “Boss I knows yous got moah sense dan dis yeah niggah,” but “a man whats got no money is as well off on one side of the river as on de other.”

All the while, Washington acted both openly and covertly to defend African American civil and political rights. He organized political protests against disfranchisement, and when political action failed he surreptitiously sponsored lawsuits to challenge voting discrimination, most notably Alabama’s 1901 Constitution. He secretly spent his own money to bring suits against segregation on railroads, discrimination in jury selection, and peonage. His secretary used pseudonyms to pass his money and coded instructions to lawyers. Washington’s clandestine manner shielded him and his institution from southerners who would not have tolerated open challenges to white supremacy.

He was forthright in his rhetorical challenges, though, speaking publicly against the many wrongs inflicted on Blacks. Th roughout the 1890s, he condemned lynching, including evidence showing that only a small portion of those lynched were charged with rape, the common justification. Lynching did not deter crime, Washington declared, but it did degrade whites who participated, and it gave the South a bad name throughout the world.

Washington constantly tried to improve the image of African Americans. A more positive reputation for Black Americans was needed to defuse some of the explosive feelings that had been building against Blacks since Reconstruction, especially during the 1890s. Washington frequently sent information to both Black and white newspapers that contradicted the prevailing negative images of Blacks by showing their economic and educational achievements. Up from Slavery represented his ultimate statement of Black progress. “No one can come into contact with the race for twenty years as I have done in the heart of the South,” he wrote, “without being convinced that the race is constantly making slow but sure progress materially, educationally, and morally.”

Washington’s public relations campaign relied on the simple strategy of presenting a competing image of African Americans, one less threatening in all ways. Washington insisted that ordinary economic and moral virtues were not only the proper goals for African Americans but also the very ones they were now pursuing. He made avoiding conflict a central part of his strategy. “Controversy equalizes wise men and fools, and the fools know it,” he noted. He knew what some modern-day public relations experts teach public figures caught in the midst of controversy: answering criticism often only fuels a public relations crisis.

Running through all Washington’s public efforts was a defense of Black education. An attack on Black education intensified over the course of the 1890s, as many whites accepted the belief that educating Blacks “spoiled a good field hand.” In every speech, Washington dwelt on the growing value of African American education. He had to turn back the attack on Black education, or the purpose of his life would be defeated.

After 1900 the Institute exported its ideas for Black uplift far beyond its small Alabama town. Tuskegee’s first involvement on the African continent came through its partnership with a company developing a farming operation in the German colony of Togo in West Africa. In 1900 three Institute graduates, one faculty member, and a large selection of supplies were deposited at Togo. The Africans receiving them had no animals to pull the wagons the Tuskegeeans had brought, but they readily hoisted them—and all the other supplies—on their heads and hiked forty miles inland to the place designated for farming. The experiment turned into a great trial for the Americans, because neither they nor the oxen they secured to pull farm equipment could withstand the insect-borne diseases. In the end, the Africans themselves pulled the plows, planters, and cultivators to produce twenty-five bales of cotton during the first season. Over the next few years, nine Tuskegee graduates worked in Togo, and four of them died there. The one who stayed established an agricultural school that trained two hundred Togo men in farming and would have doubtless done more except that he too died in 1909.

If Washington helped German colonialism, he held no illusions about the Congo Free State, where King Leopold had imposed a horrific rule over the native peoples. Washington knew the Europeans were up to no good in the big colony along West Africa’s great river. When reports of forced labor and police brutality surfaced in the U.S. in 1904, Washington took the lead in protesting the inhumanity. He wrote articles for the Congo Reform Association, called on Pres. Theodore Roosevelt to pressure Belgium to change its policies, and joined his friend Mark Twain in protests to expose the inhumanity of the Belgians.

In 1901 his influence with President Roosevelt—who hosted Washington for dinner at the WhiteHouse that same year in order to get the Tuskegeean’s advice about patronage appointments in the South—suddenly made Washington a threatening character to much of the white South. Soon Washington’s public relations effort was challenged by white supremacist politicians and writers. More than anyone else, the writer Thomas Dixon popularized the myth that Reconstruction had degraded the white South. His writing, beginning with the novel The Leopard’s Spots in 1902, promoted the feelings of a South besieged by the U.S. government. Dixon denounced Washington’s educational mission as a subterfuge for racial equality. Washington was, Dixon declared, training Blacks “to be masters of men, to be independent, to own and operate their own industries, plant their own fi elds, buy and sell their own goods, and in every shape and form destroy the last vestige of dependence on the white man for anything.”

A more direct attack on Washington came from his own congressman, J. Thomas Heflin. In his 1904 campaign, Heflin attacked Washington at the Tuskegee courthouse. He drew a straight line from Washington’s political influence to demands for social equality: “If Booker Washington didn’t believe in social equality, he wouldn’t do as he is doing.” Heflin insisted that Washington was secretly scheming to get him defeated. “If Booker interferes in this thing there is a way of stopping him. . . . We have a way of influencing negroes down here when it becomes necessary.” The threat of lynching was only implied, but no one hearing the congressman missed his message.

By 1905 Washington also faced sharp criticism from his side of the color line. A small contingent of African Americans had already rejected Washington’s standing as the leader of Black people. To them he was a sycophant to white racists by his unwillingness to demand political and civil rights openly. They were a small group, composed of a few hundred prosperous, educated families in the North, but they made themselves heard.

It soon emerged that the most influential of his Black detractors was W. E. B. Du Bois, the first African American PhD from Harvard University. Du Bois started out as a friendly acquaintance of Washington, even considering offers to teach at Tuskegee. In the 1890s, his own approach to Black progress also emphasized economic self-help and de-emphasized political action. But when Du Bois moved to Atlanta in 1897, he confronted the ugly race relations of the South, which he interpreted as evidence of the misguided nature of Washington’s leadership. Part of his disaffection was personal. Du Bois sought appointment as the head of Black schools in Washington, D.C., but was passed over for the job. He blamed Washington, whose endorsement he sought and received, for his failure to be appointed.

The estrangement became clear in Du Bois’s 1903 Souls of Black Folk. Insisting that Washington accepted Black disfranchisement—when in fact they had fought side by side against anti-Black voting laws in Georgia—Du Bois argued that Blacks had to insist on political rights if ever they were to protect themselves from white oppression. Du Bois claimed that Washington’s promotion of industrial education for Blacks came at the expense of higher education in the arts and humanities, when he well knew that Washington raised money for Black liberal-arts schools Fisk and Howard Universities. Du Bois faulted Washington for embracing conventional American values. “Negro blood” had a “message for the world” that soared above the commonplace preoccupations of white Americans. Washington’s program, on the other hand, “naturally takes on an economic cast, becoming a gospel of Work and Money to such an extent as apparently almost completely to overshadow the higher aims of life.” In 1905 the criticism of Washington resulted in the creation of a new African American organization, the Niagara Movement, led by Du Bois.

It was a bitter irony to Washington that his acceptance of conventional American values made him enemies to both northern Black intellectuals like Du Bois and southern white supremacists led by Heflin and Dixon, who promoted white hostility to Washington’s strategy for Black advancement. The Black intellectuals and white-supremacist leaders hated Washington for essentially the same reason: the Tuskegee principal understood the white world’s values all too well and was far too determined to master them.

Washington’s leadership was undermined when in 1906 Theodore Roosevelt dismissed from the U.S. Army a group of African American soldiers accused of shooting civilians at Brownsville, Texas. Listening only to the white army investigators, the president allowed the Black soldiers no hearing and ignored the evidence that showed it unlikely that all—and perhaps that any—of the Black soldiers were guilty. Washington tried but failed to dissuade Roosevelt from the harsh action. One prominent African American told Washington that when he became Roosevelt’s adviser people believed that he guided the president, and thus “in the minds of many you are held responsible for the dismissal of the colored soldiers.” Known by the company he kept, Washington’s reputation among Blacks declined with Roosevelt’s betrayal.

In later years Washington identified further wrongs perpetrated against African Americans. In 1912 he wrote that Blacks in the West Indies had a better chance to receive an academic education than those in the United States. Jamaica had “neither mobs, race riots, lynchings, nor burnings, such as disgrace our civilization.” Southern states placed a higher monetary value on leased convicts—$46 per month—than they did on Black schoolteachers, who earned only $30. Washington pointed to the Alabama county that spent $15 on each white child every year and 33 cents on each Black student. His last statement on race relations rejected segregation because it was “unjust . . . unnecessary . . . inconsistent . . . [and] it has been administered in such a way as to embitter the Negro and harm more or less the moral fibre of the white man.”

Such criticism of American race relations marked a departure in tone and interpretation from Washington’s earlier emphasis on the positive. The founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 had brought together various constituencies, including the failing Niagara movement, into an organization to protect Black rights legally. Washington had anticipated all of the NAACP’s successful civil rights efforts. In the two decades prior to the NAACP’s founding, he had made public protests against discrimination on railroads, lynching, unfair voting qualifications, and discriminatory funding in education. After 1909 he also spoke out against segregated housing legislation and discrimination by labor unions. Washington arranged and financed lawsuits challenging disfranchisement, jury discrimination, and peonage. And he campaigned constantly through his public statements and press releases against the pernicious images projected in the media and popular culture about Blacks, as he would protest in 1915 the showing of Birth of a Nation, the motion-picture version of Dixon’s novels.

After Washington died in 1915, he was initially remembered as a Black hero. Schools, parks, and even businesses were named in his honor. Public institutions across the United States used the name extensively to memorialize Black achievement. For almost two generations after his death, scores of schools, parks, community centers, libraries, and streets were named for Booker T. Washington. As public high schools for Blacks were built for the first time in many southern communities in the 1920s and 1930s, Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver became the most likely designation for the schools. The symbolism of this practice was perhaps elastic: the Tuskegee legacy may have been viewed as acceptable to powerful whites in the Jim Crow South when other Blacks of note might not have been, but Blacks independently embraced these names as symbols of their own success. Black-owned businesses often adopted Washington’s name and his image to suggest racial pride, and they needed no white consent to do so.

Black scholars in the 1920s affirmed that popularity. Horace Mann Bond of Alabama State University noted that no other African American had commanded the personal following among the masses of southern Blacks that Washington had gained through direct contact with them. Washington “alone represented a well defined school of opinion which was supported by the rank and file of the race.” In his effort to document a constructive history of black progress, Carter G. Woodson wrote that “no president of a republic, no king of a country, no emperor of a universal domain of that day approached anywhere near doing as much for the uplift of humanity as did Booker T. Washington.”

But in the 1960s, Washington was often called an Uncle Tom who sold out his own people to secure his power and delayed the coming of Black freedom. Young African Americans thought he was nothing like the great new leader of American Blacks, Martin Luther King Jr., who marched into the face of racial bigotry and then went to jail in protest against injustice. Washington had accommodated segregation and discrimination rather than challenge it, they said. Washington’s rival Du Bois became the paradigm of Black virtue from the past.

A significant portion of those disparaging Washington were historians who should have been alert to the fallacy of anachronism. In fact they were only too willing to apply the 1960s’ expectations of protest on a man who lived two generations before. Nearly all writers followed Du Bois’s lead in making Washington a villain in the telling of African American history.

This distortion of Washington contributed to a narrowing of the limits Americans have put on Black aspirations. His emphasis on educational and economic development became a lost artifact for most Americans thinking about how to integrate minorities in our society. This was ironic, because Washington’s ideas inspired and instructed struggling people all over the Third World in the twentieth century. The main lesson that people around the world took from Booker Washington—but too few Americans elicited from his life—was that hope and optimism were crucial ingredients in overcoming the obstacles of past exploitation and present discrimination. Washington’s style of interracial engagement was almost forgotten: He put a premium on finding consensus and empathizing with other groups, and by his example, encouraged dominant groups to do the same. He cautioned that when a people protest constantly about their mistreatment, they soon earn the reputation as complainers, and others stop listening to their grievances.

Washington’s response to his circumstances reflected a sophisticated mind that had contrived a complex means for achieving high-minded goals. His life was not only a struggle up from slavery but also a great effort to rise above history. Given the fate of his historical reputation, that remains the great challenge of his life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed