there were prominent Catholic politicians. In 1881 voices from Catts’s two home states cheered when west Florida’s Charles W. Jones—a Catholic who emigrated from Ireland at the age of ten—was re-elected to the U.S. Senate. “No

member of the Senate has achieved a wider or more deserved reputation which, we may say, is coexistive with the limits of the Union,” proclaimed a Montgomery, Alabama, newspaper. Jones’s term, however, was nothing short of disastrous. In 1885 he retreated to Detroit where he began showing signs of mental illness, while also hopelessly pursuing a wealthy love interest. One Michigan newspaper dubiously tabbed him, “A Love-Mad Man.” By 1888 Jones lost his senate seat, and soon the ex-senator landed in an insane asylum, where he died in 1897.

Despite Jones’s inglorious demise, obituaries emerging from Florida and Alabama enshrined his memory, glossed over his final years, and celebrated his political accomplishments and sincere faith. Yet, when Catts arrived, the mere thought of a Catholic politician horrified many non-Catholic voters in this region. Immigration no doubt fueled this ideological change. While most of America’s

new arrivals after the Civil War had settled in northern urban centers, immigrants, many of them Catholic, also filtered southward when Dixie began industrializing. The result was a nativist backlash both in the South and throughout the nation, as those with generational roots in America worried that the newcomers would fundamentally overhaul America’s character and usher in “Roman rule.” Nurturing the paranoia, Missouri’s Wilbur Phelps began publishing The Menace, an anti-Catholic periodical that attracted 1.5 million subscribers by the 1910s. In Atlanta, Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine joined the fray, printing headlines like, “Th e Roman Catholic Hierarchy: The Deadliest Menace to Our Liberties and Our Civilization,” and “How the Confessional Is Used by Priests to Ruin Women.”

Birmingham was exceptional in both attracting Catholic immigrants and generating nativist hostility. In 1908 Birmingham had only 38,000 residents. In two years, with the rise of iron and steel mills, greater Birmingham grew to 132,000. Th at number swelled to two hundred thousand a mere decade later. By 1920 the “Pittsburgh of the South” had the highest Catholic population in Alabama, boasting twelve Catholic churches. Not coincidently, the city also had a strong Klan presence, along with a secret fraternal group known as the True Americans.

In 1916 Birmingham’s anti-Catholic contingent was delighted when Catts, fresh from his victory in Florida, arrived in the city to give an address. “The Catholics were about to take Florida,” he proclaimed, “and I told the people

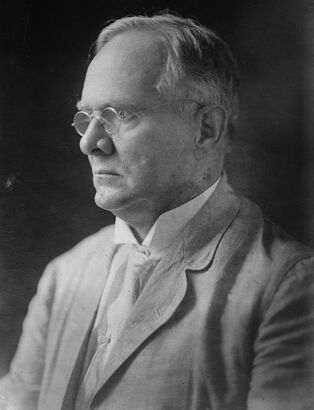

about it wherever I went.” The True Americans publicized the speech, using it to advance their agenda. Meanwhile, one lonely voice of dissent channeled the fears and frustrations of the city’s Catholics. Writing to a local newspaper, Fr. James E. Coyle, a native of Ireland and the priest of

Birmingham’s Saint Paul’s Church, acerbically condemned Catts’s rhetoric to “the malodorous gutter press of Georgia and Missouri.”

this point, the priest was accustomed to public debate, as well as censure from his bishop. In 1915 Coyle penned a Saint Patrick’s Day poem that expressed his

staunch support for Irish independence, as well as his wish for England’s defeat in the Great War. Critics responded to the priest, labeling him un-American and

un-Christian. In Mobile, Bishop Edward E. Allen caught wind of the dustup and

wrote to Coyle, asking that he “bring the discussion to a speedy close” and heed the instructions of Pope Benedict XV “to remain neutral and let the voice of Faith, Hope and Charity alone be heard about the clang of arms.”

In matters such as these, Bishop Allen tended to be pragmatic, preferring to keep the peace instead of ruffling feathers. But when tragedy struck Birmingham’s Catholic community, Allen set aside his neutrality. On August 11, 1921, a heated confrontation between Edwin R. Stephenson, a Methodist minister, and Father Coyle ensued on the rectory porch of Saint Paul’s. The point of dispute was Stephenson’s eighteen-year-old daughter, Ruth, who Coyle had just wed to Pedro Gussman, a forty-three-year-old Catholic and Puerto Rican immigrant. As the shouts grew louder, Stephenson drew a pistol, fired, and

mortally wounded the forty-eight-year-old priest. At Coyle’s funeral, Bishop Allen spoke with furor and forthrightness, blaming the toxic atmosphere in Birmingham on “disreputable politicians and secret societies,” who had betrayed “American principles of charity, justice and equality for all.”

As Stephenson’s case headed to trial, reporters from near and far flooded the city. The trial gained national attention, and one northern reporter labeled Birmingham “the American hot bed of anti-Catholic fanaticism.” One of

Stephenson’s attorneys was Hugo L. Black, a 1937 appointee to the U.S. Supreme Court. While the evidence against Stephenson was overwhelming, the all-Protestant jury (with a Klansman as the foreman) ruled him not guilty. The judge resolved that “no one can properly criticize the honest verdict of twelve honest men.”

The judge’s prediction was wrong. In public statements, Emmet O’Neal, the former governor of Alabama and a Presbyterian, railed against the verdict, which he said, “made an open season in Alabama for the killing of Catholics.” Many

other non-Catholics in the state would share his outrage. By 1941 Helen McGough, a parishioner of Coyle’s, remembered the priest’s death marking the final chapter of anti-Catholicism in Alabama. “After the trial,” she elaborated, “there followed such revulsion of feeling among the right-minded who before had been bogged down in blindness and indifference that slowly and almost unnoticeably the Ku Klux Klan and their ilk began to lose favor among the people.”

Indeed, Alabama and Florida have come a long way since the days of Sidney Catts and the True Americans, with Catholics now a mainstay in public life and politics. And in Birmingham, organizers of the Father James E. Coyle Memorial Project have committed to keeping the priest’s memory alive by hosting public talks and maintaining a website with pictures, personal writings, and stories about the priest. Birmingham’s Jim Pinto directs the project, hopeful, as he writes on the website’s welcome page, “that the sharing of the life and death of this holy man may promote greater understanding, reconciliation and peace

among all of God’s children.”

This feature was previously published in Issue 105, Summer 2012.

About the Author

Arthur Remillard is assistant professor of religious studies at Saint Francis University (Loretto, PA). He is the author of Southern Civil Religions: Imagining the Good Society in the Post–Reconstruction Era(University of Georgia Press, 2011) and the book review editor for the Journal of Southern Religion. Joshua D. Rothman, standing editor of the “Southern Religion” department of Alabama Heritage, is associate professor of history at the University of Alabama and director of the university’s Frances S. Summersell Center for the Study of the South, which sponsors this department.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed