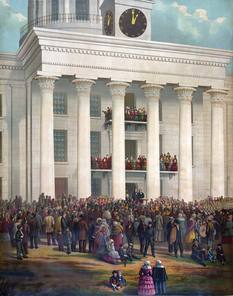

“The Starting Point of the Great War Between the States.” James Massalon based this 1878 painting of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis on a photograph taken that day and owned by William C. Howell of Prattville. The photo is now held by the Alabama Department of Archives and History. (Library of Congress)

“The Starting Point of the Great War Between the States.” James Massalon based this 1878 painting of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis on a photograph taken that day and owned by William C. Howell of Prattville. The photo is now held by the Alabama Department of Archives and History. (Library of Congress) Alabama had played a central role in establishing the Confederate States of America, in reaction to Abraham Lincoln's election the previous fall. After seceding from the Union, Alabama officials immediately invited other seceding states to convene in Montgomery in order to form a new government. Being centrally located along main rail lines, delegates from the other Deep South states—Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Texas—could travel to Montgomery with relative ease. As Lincoln traveled to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration, these delegates made their way to Montgomery, a town poised in its temperate February climate to be the heart of a new nation.

After Davis's inauguration on February 18, Montgomery embraced its new role as the capital of the Confederacy. At first, the bustling river port seemed a good fit for the new nation, and its citizens gladly welcomed government officials to their city. But during the spring months—as men seeking political and military business with the Confederate government descended on the city—Montgomery's population swelled to twice its normal size, leading to overcrowded conditions. Spring temperatures climbed in the southern capital, and tempers began to flare. Visitors quickly tired of the unpaved roads and rustic accommodations. And with summer approaching, the arrival of mosquitoes brought fears of disease. If visitors were growing testy with life in the new Confederate capital, the city's inhabitants were growing equally irritated with the constant presence of strangers in their community. But there was much work to do.

The states of the Deep South zealously labored to convince the states of the Upper South to join their new nation. After seceding on April 17, the state of Virginia invited the Confederate government to move its capital to Richmond. The city was larger and could better accommodate the government of the Confederacy, and relocation of the capital would also please Virginia's many wealthy citizens. To Davis and the Confederate Congress, moving the government during the summer seemed logical. Nevertheless, according to Thomas Cooper De Leon, a South Carolinian living in Montgomery, the city's natives "began to wail." Despite their grumbling "that the continuance of the Congress there for one year would render the city as perfect a Sodom as Washington," Montgomery's citizens bristled when the government made plans to move the capital. Nevertheless, on May 29, Huntsville's Southern Advocate issued a report from Montgomery that "all of the Congressmen have left the city, with one or two exceptions." On July 20, 1861, the Confederate Congress reconvened in Richmond, Virginia. Montgomery's service as the capital of the Confederacy had ended.

Author

Megan L. Bever is currently a doctoral student in the department of history at the University of Alabama. Her research interests include the nineteenth-century South and the Civil War in American culture.