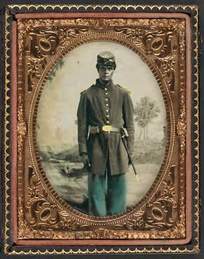

This hand-colored tintype portrays an unidentified African American soldier wearing a forage cap with the insignia of the 103rd Regiment’s Company B. (Library of Congress)

This hand-colored tintype portrays an unidentified African American soldier wearing a forage cap with the insignia of the 103rd Regiment’s Company B. (Library of Congress) One soldier, George Buck Hanon, who was serving in Bridgeport, Alabama, wrote that the white officer in his regiment kept the black soldiers “bys hand cuf [sic] ever day and night” though he could not understand the purpose of restricting the movements of African American troops. Hanon bemoaned that when “mens wifes [sic] comes here to see them” the white officer would “not alow [sic] them to come in to they lines” nor would he allow “the men to go out to see them after the comg [sic] over hundred miles.” Unlike white soldiers, whose wives were allowed to pay visits to camps, many black troops were denied the same privilege, due to the racist practices of white officers within the Union army. Similarly, black soldiers faced grave dangers when engaged in combat. Like the victims of the Fort Pillow massacre, other black soldiers were executed by Confederates who were infuriated by the Emancipation Proclamation and the subsequent arming of black soldiers.

Despite the hardships, black troops continued to fight for their freedom. In addition to Hanon and other African American troops serving in Bridgeport, many black soldiers played important roles in the Union victory at the Battle of Fort Blakely, which occurred in April 1865, on the shore of Mobile Bay. This battle remained contentious for decades, as allegations circulated that the black soldiers continued firing on Confederates who had surrendered. (It remains unclear what actually happened.) And as the war’s end neared, the Fifty-first US Colored Infantry traveled from Mobile to Montgomery, Alabama, by boat–a sight to behold for Alabama blacks, who lined the river banks and cheered. Freedom was coming.