|

In the midst of the war that swept the state in the spring and summer months of 1862, Alabamians remained deeply divided. While many residents of the southern portions of the state wholeheartedly supported the Confederacy, in the northern counties, away from the Black Belt, many staunch Unionists remained.

Although the spring months had brought Union occupiers to the northern portions of Alabama, many of Alabama’s communities and citizens continued to throw their support behind the Confederacy.

After defeating the Confederates at Shiloh in early April of 1862, federal forces gained access to the Tennessee River Valley. Within a few days, on April 11, a detachment of Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio captured Huntsville, Alabama. Under the leadership of Maj. Gen. O. M. Mitchel, eight thousand Union troops took control of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad and used the locomotives to move quickly through the territory, occupying most of northern Alabama in one day. A few weeks later, on May 2, Union Col. John Basil Turchin occupied Athens. His forces quickly severed the railroad and forced the Confederate Army to abandon its supplies and head south.

In the early months of 1862, the war came to Alabama. Federal troops under the leadership of Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson along the Tennessee River. The Union Army’s successes opened up the Tennessee River Valley to invasion, and in February Union gunboats arrived in Florence, Alabama, on a mission to destroy Confederate supplies. Located in Lauderdale County, Florence was home to many Unionists, who greeted the arriving Union troops enthusiastically, hoping their stay in the city would liberate it from the hands of Confederate Alabamians.

The summer of 1861 brought the first major battle of the Civil War. Both the Confederacy and the United States had been amassing volunteers during the spring months, and many people believed that the conflict would be over by the end of the year. In fact, Parthenia Antoinette Hague, a young woman from Eufaula, Alabama, remembered that many of the "soldiers, in their new gray uniforms, all aglow with fiery patriotism" feared that "the last booming cannon would have ceased reverberate among the mountains, hills, and valleys" before they could arrive in Virginia. But their fears of missing battle were unfounded.

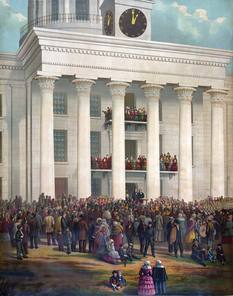

“The Starting Point of the Great War Between the States.” James Massalon based this 1878 painting of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis on a photograph taken that day and owned by William C. Howell of Prattville. The photo is now held by the Alabama Department of Archives and History. (Library of Congress) “The Starting Point of the Great War Between the States.” James Massalon based this 1878 painting of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis on a photograph taken that day and owned by William C. Howell of Prattville. The photo is now held by the Alabama Department of Archives and History. (Library of Congress) In July 1861, a cradle was robbed in Montgomery. The infant Confederacy—not yet six months old—would grow up far from the heart of Dixie. For the enterprising and ambitious inhabitants of Montgomery, this had not been the plan. Alabama had played a central role in establishing the Confederate States of America, in reaction to Abraham Lincoln's election the previous fall. After seceding from the Union, Alabama officials immediately invited other seceding states to convene in Montgomery in order to form a new government. Being centrally located along main rail lines, delegates from the other Deep South states—Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Texas—could travel to Montgomery with relative ease. As Lincoln traveled to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration, these delegates made their way to Montgomery, a town poised in its temperate February climate to be the heart of a new nation. In the spring of 1861, the new Confederate government struggled to organize itself in Montgomery, Alabama. Newly elected President Jefferson Davis sought a way for the Confederate states to exist without provoking a war with the United States.

On Christmas Eve of 1860, Gov. Andrew Moore reluctantly called for a secession convention in Alabama. The results of November’s popular election had been confirmed by the Electoral College, and Abraham Lincoln prepared to become the next president of the United States. Convinced that Alabama needed to protect itself from a federal government controlled by Republicans, who threatened the future expansion of slavery, delegates from throughout the state convened in Montgomery on January 7 to discuss secession.

During the fall of 1860, white Alabamians remained divided politically. Radicals continued to campaign for John Breckenridge in the presidential election, prompting bitter responses from supporters of John Bell and Stephen Douglas. The Southern Advocate of Huntsville complained that “United, the Democratic party could have beaten Lincoln easily: But the Alabama Convention at Montgomery in January, its instructions, bursted the party.”

As the humid heat of summer enveloped Alabama, the upcoming 1860 presidential election continued to occupy the minds of white men throughout the state. Secessionists, led by William Yancey, had managed to thwart efforts at compromise at the Charleston Convention in the spring, but many Alabamians still believed that their radical position would doom southern interests when November arrived.

|

Becoming Alabama:

|

|