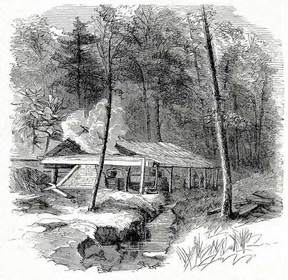

Whiskey stills, both legal and illegal, provided Etowah County with much of its income in the late 19th century. Whiskey stills were often hidden deep in the woods, like the still in this 1867 sketch, to discourage investigators from unwanted visits. (Courtesy Alabama Archives)

Whiskey stills, both legal and illegal, provided Etowah County with much of its income in the late 19th century. Whiskey stills were often hidden deep in the woods, like the still in this 1867 sketch, to discourage investigators from unwanted visits. (Courtesy Alabama Archives) Deep ravines pockmarked with crevices and thickly tangled underbrush, where wildlife greatly outnumbered human inhabitants, defined this isolated region in the late nineteenth century. In addition to camouflaging the stills, the landscape deterred many investigators from examining the area too closely. But when federal revenue agent Holman Leatherwood and his partner Peevy began traversing the hills and valleys of Sand Mountain, they quickly ran into bigger challenges than the topography. The two had been sent to collect taxes from the owners of legal stills and to destroy any operations that were illegal or whose owners refused to pay the federal tax. Tax collectors are never popular, but in the aftermath of the war, federal agents served as an unwanted reminder of the Confederacy’s loss and attracted more hostility than normal.

According to the Gadsden Times, the two lawmen had destroyed several stills before someone shot both Peevy and his horse. Peevy proved luckier than the horse and survived his wounds. As his partner recovered, Leatherwood served as the sole enforcer of federal liquor laws, and weeks later he took the fateful trip to Marion Neugen’s still house.

“No one man can safely ride over these mountains and cut up stills and bum still houses,” the Times would declare afterward in a June 4 article. “It is folly to attempt it. The men who have tried it have so far met with a bloody reception.”

Tax collectors are never popular, but in the aftermath of the war, federal agents served as an unwanted reminder of the Confederacy’s loss and attracted more hostility than normal.

The farmer notified the authorities, and more than seventy local men gathered to form search parties. The men found fresh horse tracks and, thinking they were Leatherwood’s, followed them to Marion Neugen’s still house. Just outside the building, two heavy pools of blood had puddled. But, after an intensive two-day effort, the search was called off, and only law officials continued to hunt for Leatherwood, now presumed dead. Later, a pair of bloodied men’s trousers and a pocket watch, both believed to be Leatherwood’s, were found near the still house.

Though the evidence seemed to implicate Marion Neugen’s involvement in Leatherwood’s murder, some were hesitant to accuse him. “It is evident that Leatherwood has been murdered,” the Times said, “and his body either hid in a cave in the mountain or in the bottom of Short or some other creek. We want it distinctly understood that the good people of our county are in no way responsible for these outrages.”

Within a few weeks of Leatherwood’s disappearance, Marion Neugen, his teenage son Mefford, and their coworker Berry Word, were arrested and turned over to federal authorities. The Times warned its readers against quick judgment of the suspects, saying, “Murder will out, and sooner or later the guilty party or parties in this case will be known.” Local officials turned the suspects over to the federal authorities, and the search for Leatherwood's body or other incriminating evidence continued.

Bruce Crowe of Pulaski, Tennessee, claimed he had seen Leatherwood alive in Waco, Texas, a week after the alleged murder. The Montgomery Advertiser contacted the Waco Examiner for verification and received an answer saying that Leatherwood did, in fact, reside near a local river. The Examiner urged Alabama authorities to wait until the truth was unveiled before determining the fate of the accused murderers. “The mistake could not be remedied after the hanging,” it warned.

Once the alleged sightings of Leatherwood were made public, the Gadsden Times changed its attitude toward the Neugens and Word. Instead of disassociating the upright citizens of the city from the alleged killers, it embraced the defendants’ innocence and lambasted their supposed abuse by vengeful federal authorities. The Times further alleged that prior to his disappearance Leatherwood stole more than a thousand dollars from the government and fled to Texas to start a new life. The paper accused the area’s other federal officers of conspiring with Leatherwood and framing innocent men for their friend’s nefarious deeds. With no body, rumors that Leatherwood was the culprit rather than victim, and allegations of governmental duplicity, all charges against the defendants were dropped.

No legitimate evidence was ever produced to prove that Leatherwood had stolen government funds. Nor did the missing agent ever surface again. His father offered an eight-hundred-dollar reward for the return of his son’s body and led several searches of the Coosa River with no success. Etowah County erected a memorial to the county’s slain lawmen some years later. But with his fate still a mystery, Holman Leatherwood’s name was not included.

Author

Pamela Jones is a freelance writer and researcher based in Birmingham. Her particular areas of interest in Alabama history are true crime and the state between the two world wars. She is a history instructor at a Birmingham college and writes corporate histories.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed