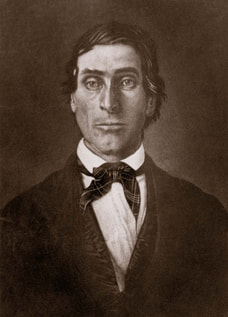

Daniel Pratt, a native of New Hampshire, moved to Alabama, where he established the town of Prattville and an international business building cotton gins. (Photo Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Daniel Pratt, a native of New Hampshire, moved to Alabama, where he established the town of Prattville and an international business building cotton gins. (Photo Alabama Department of Archives and History) Pratt was born in Temple, New Hampshire, on July 20, 1799. He was the son of yeomen farmers, Edward and Asenath Pratt, and was the fourth of six children. Coming from a large, deeply religious family that was on a strict budget later played a key role in Pratt’s establishment of Prattville. Pratt remained in Temple until age sixteen, when he decided to pursue a trade. In 1815 Pratt began his first apprenticeship in carpentry, and four years later he moved to the South, arriving in Savannah, Georgia in 1819. It did not take long for Pratt to create a life for himself in the still-developing region, and by 1827 he had become one of the leading carpenter-architects in the area emcompassing the towns of Macon and Milledgeville, then the state capital of Georgia.

For a decade, from 1821 to 1831, Pratt displayed notable artistry in the elite homes that he constructed in and around Milledgeville. Today, historians refer to Pratt’s work as “Milledgeville Federal” in style and consider many of the structures attributed to him to be of national architectural significance. Three of the houses credited to him in the vicinity of Milledgeville—the Williams-Orme House, The Homestead, and Boykin Hall—still stand, and another, the Gordon-Blount-Banks House, has been moved to Newnan, Georgia. The homes built by Pratt in Georgia gave him the practical experience necessary to plan the village he would soon build in Alabama. Milledgeville was also the center of a growing economy based on cotton and the plantation system, and during his time there, Pratt became interested in cotton gin manufacturing.

In 1831 Samuel Griswold, the South’s pioneering gin manufacturer, was impressed by Pratt’s accomplishments in carpentry and chose him as superintendent for his factory in Clinton, Georgia. The firm of Griswold & Pratt easily dominated the business in central and eastern Georgia, even extending into the Carolinas. Before long the two were considering branching outwards to Alabama. The central region of the state specifically was poised to become a major center for the cultivation of cotton, and situating cotton gin production sites on the Alabama River would provide greater access to the booming southwestern markets. Griswold soon abandoned the idea, however, because of his fear of the local Alabama Creek Indians, who were reported to inhabit the coveted marshy and fertile land. Pratt, however, decided to proceed and relocated to Alabama in 1833. He brought his wife, Esther, whom he had married in 1827; enough material for fifty cotton gins; and two enslaved people.

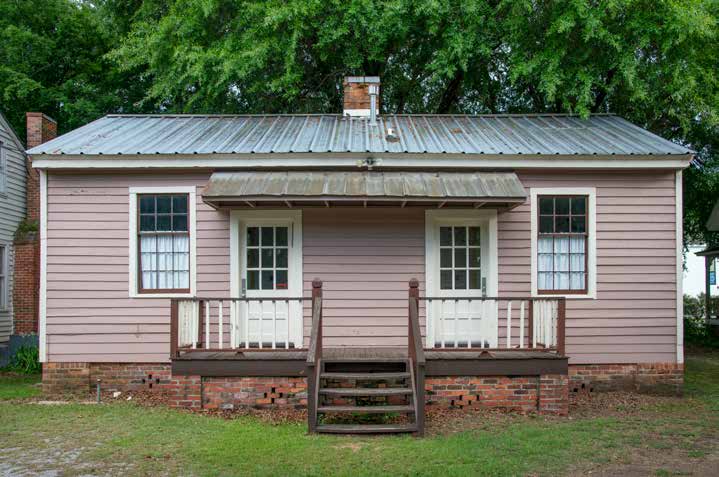

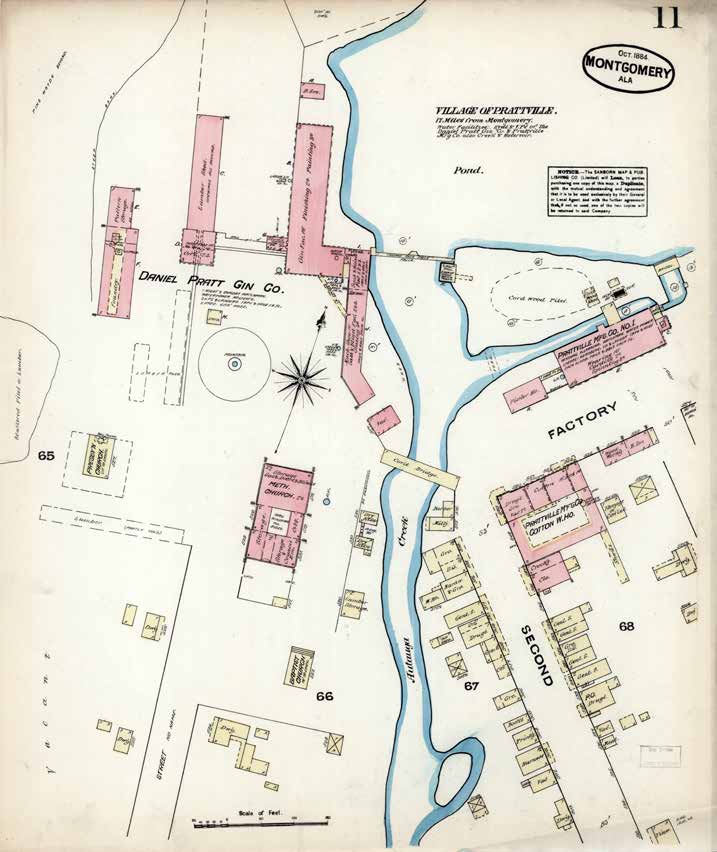

Pratt’s first cotton-gin factory was established in 1839, the same year as the founding of Prattville. He quickly prospered in the state and sold his machines to Alabama’s Black Belt planters just at the time the region was experiencing major growth. When Pratt arrived in Alabama, the region’s population was booming with migrants searching for new land. In particular, Autauga County, where Prattville is located, felt this impact. During the 1830s its population contained close to 50 percent enslaved people, but this balance soon began to shift. In 1840 some 14,343 residents were recorded in Autauga County, including 6,217 whites and 8,125 enslaved African Americans. Ten years later 14,879 residents were recorded, with an increase in the number of African Americans to 8,749 and whites to only 6,274. As a result of this growth, Pratt began to develop the infrastructure of the bustling town that surrounded his mill. In 1840 he oversaw the construction of a blacksmith’s shop, a flour and grist mill, the town’s first Baptist and Methodist churches, and his personal residence—all along the Autauga Creek. The town also included approximately six to eight houses for

mechanics—modest, saddlebagged houses constructed for both hired and enslaved mill workers, which included only the necessities to provide an adequate place for shelter and domestic life. Pratt’s ideal vision for a self-sufficient southern society was clear: a network of small manufacturing villages that each provided employment, housing, and education guided by religious instruction for its residents and workers.

Prattville’s economy led to a diverse community and workforce. Through the work of Pratt’s skillfully trained employees, his operation quickly became not only Alabama’s first major industry but also the largest producer of cotton gins in the world. His sales were strong in the 1840s, and from 1841 to 1844, Pratt’s mill shipped an estimated 1,951 gins, averaging nearly 500 per year. Pratt was not solely focused on economic success, however. He was also dedicated to developing an environment where his citizens would encourage one another to excel. Pratt demonstrated this idea throughout many facets in his village, and as an accomplished architect, he possessed the skills to oversee much of Prattville’s growth. That growth brought improvements, including mill houses for his hired and enslaved mill workers, in addition to schools and churches.

While Prattville’s wealthier mechanics likely owned their own homes, most mechanics (hired and enslaved) rented houses from Pratt for a nominal fee. Arranged in intervals along Autauga Creek, these small dwellings were simple in design and modest in appearance. Built of wooden framing and weather boarding, the houses were constructed with a saddlebag pen layout, commonly measuring sixteen by thirty-two feet, and designed to house two families, thus halving the actual space for each. Noteworthy features of these homes include a walled central chimney, a window hung to one side of each door, and a separate entranceway for each unit.

Central chimneys were not always a feature of housing in this period, as cooking spaces were often located outside the home. The central chimney and hearth design evolved over time for comfort. The windows set off from the doorway are also distinctive features of these houses, serving as a source of light and ventilation. Characterized by the industrialized nature of their construction and usage, these homes were meant to be sufficient for the common laborer. The nature of Pratt’s houses and mill villages attests to this ideology of successful business management, and his take on the industrialized saddlebag was perhaps best represented here. Prattville became a booming town during the nineteenth century, and the infrastructure of the village served as a model for a transition from an agrarian-based economy to an industrial economy.

Churches and religious gatherings also played a key role during Prattville’s transition. As a deeply religious man himself, Pratt ensured that all members of his village, including the enslaved, were involved in some sort of religious community. In the South following the 1830s, there was a switch from viewing the institution of slavery as a necessary evil to one that served as a positive aspect of society. Pratt’s profound concern with Prattville’s citizens and the village’s overall public image is well evidenced. Pratt had a Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian Church built along Church Street, all of which were designed by him and located directly across the street from the main gin company complex. This location provided convenient access for the many mill families who lived on the same waterfront and provided constant interaction with the laborers who likely passed by their church every day going to and from work.

As early as 1845, Pratt had established a local school for the town’s children. Records reveal that the small framed schoolhouse cost about $1,000, and Pratt hired a friend from New Hampshire as the first teacher. Unless employed in the mill, all of the white workers’ children were expected to attend the provided school or daycare. Furthermore, the Prattville Male and Female Academy, part of Pratt’s continuous efforts to help his growing community, was constructed in 1859. Designed in the Italianate style and made of brick, the school cost Pratt about $9,500 in construction costs; he also furnished the school with a large bell imported from a famous bell foundry in West Troy, New York. The Academy served for years as Autauga County’s best school. Pratt also provided the first public school building for African Americans in the area after the Civil War. The school was located near the mill site but situated outside of the town. A map from 1891 shows the site’s location on the waterfront of the Autauga Creek, but no other records of this school have been found and no one is sure when the school was actually built.

Pratt likely drew inspiration for his mill town from larger plantations of the upper South, like George Washington’s Mount Vernon and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia. Both utilized a village arrangement, including multi-family modular architecture and a number of accommodations such as schools and shops. Also like other large plantation owners, Pratt owned hundreds of enslaved people before the Civil War. However, unlike most plantation owners, Pratt was not only a wealthy slaveholder but also the founder and employer of an entire town. His role in Prattville ensured his place in the state’s history as an important pioneer in the beginning of Alabama’s transformation from a predominantly agrarian economy to a more diverse and industrial economy devoted to manufacturing.

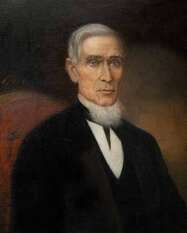

Daniel Pratt died on May 13, 1873. His adopted son, Merrill, ran the company following his death, merging with other companies to form the Continental Gin Company in 1899. (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Daniel Pratt died on May 13, 1873. His adopted son, Merrill, ran the company following his death, merging with other companies to form the Continental Gin Company in 1899. (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed