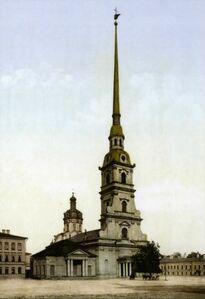

The real Princess Charlotte lies next to her husband, the Tsarevich Alexis, in the Cathedral of Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg, Russia. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

The real Princess Charlotte lies next to her husband, the Tsarevich Alexis, in the Cathedral of Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg, Russia. (Courtesy Library of Congress) According to Mobile's "princess," she feigned a serious illness just before she was to deliver her second child. After giving birth to a son, Peter, the future emperor Peter II, she faked her death with the aid of loyal servants. As a dying request, she asked her father-in-law that she not be embalmed before her burial. He acquiesced, and her funeral was a state affair. After her entombment, her servants released her from her casket and smuggled her out of the country. She claimed to endure this elaborate charade to escape her brutal, philandering, alcoholic husband.

Her fabulous tale met mostly with disbelief until one of the officers at Fort Conde, a Chevalier D'Aubant, stepped forward, saying that he had been introduced to Princess Charlotte at the St. Petersburg court. He verified that the woman was indeed the royal princess. Within a short time, the French officer and the "princess" married. Reportedly, they had a daughter while based in Mobile, and after a few years at Fort Toulouse (near present-day Montgomery), the Chevalier was recalled to France, where they lived contentedly until his death in 1765.

In recounting the story in his 1851 History of Alabama, Albert James Pickett says the woman was a servant of the princess and that he absconded with the princess's jewels clothing, and funds near the time of her death. Mobile historian Jay Higginbotham, author of Mobile: City by the Bay, writes that the woman's charade was exposed in Europe by Voltaire, who had written one of the first biographies of Peter the Great. Supposedly, a German noble saw the alleged princess walking in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris and recognized her as a wardrobe servant of the late princess. He told Voltaire, who then informed the European press of the woman's deceit. The impostor died in poverty, but her story still generates controversy. Higginbotham says he does not know the genesis of the legend, but it has circulated for more than 150 years. While some historians place the story in colonial New Orleans, most agree that the deception took place in Mobile.

The story of the true Princess Charlotte is a tragic tale of a young noblewoman forced to marry an alcoholic, perhaps mentally unstable, prince who publicly paraded his lovers in court and made no secret of his disdain for his young wife. Charlotte was only sixteen when Peter the Great traveled to Germany seeking a wife for his errant, first-born son. Historical accounts describe the young princess as exceedingly tall, thin, pock-marked, and plain, but with a generous nature. Her marriage contract with Alexis gave her twenty-five thousand reichsthaler and a carriage and allowed her to continue practicing her Protestant faith, but her children were to be raised Eastern Orthodox.

In October 1711, she and Alexis were married at the castle of the Queen of Poland. Rebuffed by the ladies of the Russian court, only her father-in-law treated her with any kindness. She bore Alexis a daughter, Natalia, in 1714, and soon became pregnant again. A few weeks before her second child was to be born, Charlotte fell down a palace staircase and never completely recovered. She died four days after giving birth to Peter in October 1715. Alexis was said to have fainted three times at her bedside. She was buried, without being embalmed, in the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul. Shortly before her death, she dictated a letter to her mother in Germany saying that despite any rumors to the contrary, she was dying of natural causes, not grief at Alexis's mistreatment. She also praised her father-in-law for his constant kindness during her unhappy years in Russia. A few years later, Alexis died of unknown cause in a Russian prison where he was tortured by his father's emissaries for his part in an attempted coup against Peter. He was buried next to Princess Charlotte.

This feature was previously published in Issue 78, Fall 2005.

About the Author

Pam Jones is a freelance writer in Birmingham with a particular interest in criminal cases from Alabama's past.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed