|

For 125 years she lay, inconspicuous, her final resting place marked with only the simplest of stones: a sandstone rock with no name, no dates, no epitaph—no inscription at all.

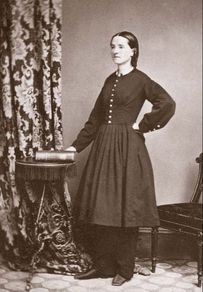

Landowners forced their tenant farmers and sharecroppers to cultivate cotton even at the expense of growing food for their families. (Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History) Landowners forced their tenant farmers and sharecroppers to cultivate cotton even at the expense of growing food for their families. (Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History) A person encountering Ida Mathis in Birmingham in the early 1900s would not have guessed that she would soon be labeled the savior of the Alabama economy. A matronly figure with a kind face, she did not resemble the “economic Moses of the South” or “Joan of Arc of agriculture,” though contemporary periodicals called her both. Today, her alliance with bankers and businessmen appears to have little in common with the usual approach of Progressive Era women, who drew upon their author

ity as mothers when pressing for social reforms. In both cases observers would be fooled. Although Mathis took an unusual approach in presenting herself as a practical farmer and businesswoman, she adopted a distinctly feminine strategy in striving for a sense of family among all community members. When the cotton market’s collapse threw the state into economic depression in 1914, she worked to convince businessmen, farmers, and urban consumers that they had a direct stake in one another’s success. Her sincerity, speaking skills, and sound financial advice drew national attention and laid the groundwork for the state’s increased food production during World War I.  Jim, the “Master of Possum Hounds,” and his wife rally the canine troops. (Photo courtesy the author) Jim, the “Master of Possum Hounds,” and his wife rally the canine troops. (Photo courtesy the author) Unlike most of our Alabama neighbors, the men in our family did not shoot deer, doves, or quail. My grandfather, Mac, and my father, Ted, did not hunt at all. My uncle, Stewart, owned no gun; our family did not approve of guns (the influence of my pacifist grandmother, "Miss Rose"). Stewart not only lived in a déclassé neighborhood; he engaged in a déclassé form of hunting. Possum hunting lost class when the southern gentility, aping the British as usual, took up fox hunting. That left possum hunting to poor folks in need of food. After they caught a possum, they fattened it for a few weeks, butchered it as they would a pig, boiled it, baked it, and served it with rich gravy and sweet potatoes. What would Miss Rose say if Stewart brought a sack of possums to her kitchen? Unimaginable! In 1944 the Birmingham News characterized the Women’s Army Corps, or WAC, post at Anniston’s Fort McClellan as being more like a sorority house on a university campus than like a military barrack housing enlisted women. Noting the bowling alley, golf course, and post club, the paper lauded the role of WACs in the war eff ort but also patronizingly saw their work as largely frivolous when compared with that of their male counterparts. As the paper observed of a woman repairing a large rifle, “[I]t is not a soldier, it’s a WAC.” Even as women who served in the WAC during World War II (WWII) faced questions about their contributions, however, they felt that serving their country was worth the trials of basic training, the low pay, and the scrutiny they received. Indeed, during WWII and the Cold War that followed, the WAC evolved to overcome these challenges by improving the benefits of women’s service, countering opposition, and ultimately illustrating its commitment to female soldiers by making the post at Fort McClellan into a permanent training facility.

One of the most well-known documents in the W. S. Hoole Special Collections Library at the University of Alabama is the journal of Sarah Haynsworth Gayle. This journal is a detailed commentary on life in early nineteenth-century Alabama as well as an account of the inward journey of a young woman. Numerous social historians, particularly those studying southern women, families, and marriage, have consulted and quoted from this manuscript. |

From the VaultRead complete classic articles and departments featured in Alabama Heritage magazine in the past 35 years of publishing. You'll find in-depth features along with quirky and fun departments that cover the people, places, and events that make our state great! Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed