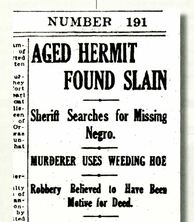

The Montgomery Advertiser ran an article on the brutal killing of "hermit" Jesse Baldwin on July 9, 1910, the day after the murder occurred. (Courtesy the Montgomery Advertiser.)

The Montgomery Advertiser ran an article on the brutal killing of "hermit" Jesse Baldwin on July 9, 1910, the day after the murder occurred. (Courtesy the Montgomery Advertiser.)

The story detailed the search for the murderers of seventy-two-year-old farmer and Civil War veteran "Captain" Jesse Baldwin. On the morning of July 8, the dying planter's beaten and bloody body had been discovered lying under the branches of a peach tree located just steps from his back porch. Employee and former slave Handy McKenzie discovered Baldwin and immediately ran to Wilcox, the nearest community, for assistance. But by the time help arrived at the plantation, it was too late. The captain was dead. His skull was crushed, and his face was pocked with deep cuts.

A ragged shoe print found at the crime scene convinced local law officials that the killers were black. Within hours of the discovery, packs of armed white men began searching the homes of local African Americans. "The most brutal murder in all the history of Conecuh County! Someone would have to pay. That this was in the minds of the posses was evident. Grimly they pushed the manhunt," according to an account of the murder in the October 1938 issue of Real Detective magazine.

"The most brutal murder in all the history of Conecuh County! Someone would have to pay. That this was in the minds of the posses was evident. Grimly they pushed the manhunt."

One local black resident, Charlie Manuel, denied any knowledge of the crime when confronted by one of the unofficial posses. They placed a noose around his neck, and dragged Manuel to a tree. The rope was thrown over a limb. As Manuel begged for mercy, members of the lynch mob pulled the rope and tightened the noose around his neck. Finally, after a few minutes, they released the rope. Manuel survived.

Remus White was not so lucky. Rumors had reached a posse led by deputy Huey Nail that White was harboring one of Baldwin's murderers. When the deputy approached White, the latter refused to cooperate, according to Nall. The deputy pulled his pistol and shot the unarmed man. The cause of death was listed as "Resisting arrest."

Within a few days of Baldwin's death, Albert Johnson, age eighteen, was arrested for the murder. An African American neighbor of the victim, Johnson was caught after attempting to sell Baldwin's stolen shotgun for $3.50. Johnson was found guilty and given a life sentence. He was sent to Kilby Prison to serve his time. Even though it was widely accepted that Johnson did not act alone in the crime, he never named any accomplices. That aspect of the case stayed cold for more than twenty years.

In the spring of 1929, Johnson managed to escape from Kilby. He eluded capture for nearly five years, but was discovered living in Buffalo, New York, in October 1933. Conecuh law officials seized the opportunity of his recapture to push Johnson for the names of his cohorts. He refused and again, the case went cold.

But a few years later, the murder of Baldwin would crack wide open, and four men convicted of participating in the crime would join Johnson in prison.

Three of the suspects, including Charlie's brother Litt, confessed, and were given life sentences. But Charlie never wavered in his proclamation of innocence. Despite his protestations and the lack of any forensic or circumstantial evidence, he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

This feature was previously published in Issue 88, Spring 2008.

About the Author

Pamela Jones is a freelance writer and researcher based in Birmingham. Her particular areas of interest in Alabama history are true crime and the state between the two world wars. She is a history instructor at a Birmingham college and writes corporate histories.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed